Interactions Between Endodontics and Periodontics: Part I

14/01/2021

Davide Guglielmi

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /var/www/vhosts/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/endodontics.styleitaliano.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /var/www/vhosts/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/endodontics.styleitaliano.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Understanding the interaction between endodontics and periodontics is of crucial importance to the clinician because of the challenges frequently encountered in the assessment, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of combined endodontic–periodontal diseases. Treatment and prognosis of endodontic–periodontal diseases vary, depending on the etiology, pathogenesis and correct recognition of each specific condition. Therefore, understanding the interrelationship between endodontic and periodontal diseases will enhance the clinician’s ability to establish the correct diagnosis, assess the prognosis of the teeth involved and select a treatment plan based on biological and clinical evidence.

The dental pulp and the periodontium are connected by three main communication routes:

exposed dentinal tubules;

accessory canals;

apical foramen.

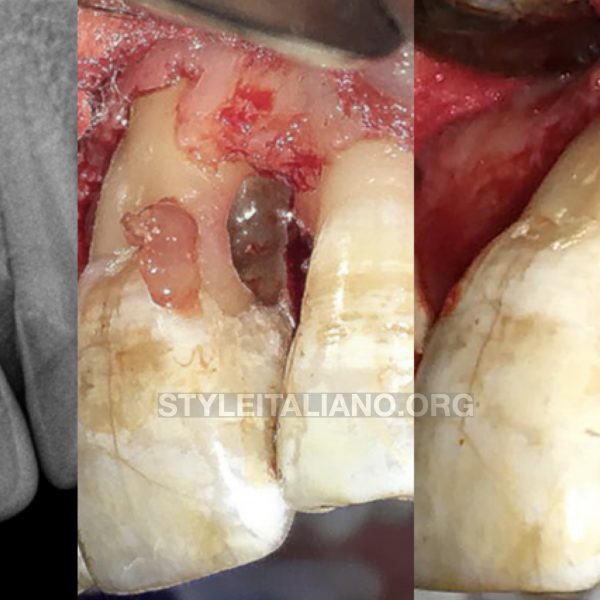

Fig. 1

exposed dentinal tubules

Dentinal tubules which are exposed in cementless areas can serve as pathways of communication between the dental pulp and the periodontal ligament. The root dentinal tubules extend from the pulp to the cemento-dentinal junction with a relatively straight path and a size ranging from 1 to 3 microns in diameter. The diameter of the tubules decreases with age or in response to a chronic low-grade stimulus that causes the apposition of highly mineralized peritubular dentin. The number of dentinal tubules ranges from about 8,000 near the CEJ (cemento-enamel junction) to about 57,000/mm2 near the pulp.

Images Courtesy of Prof. Massimo de Sanctis

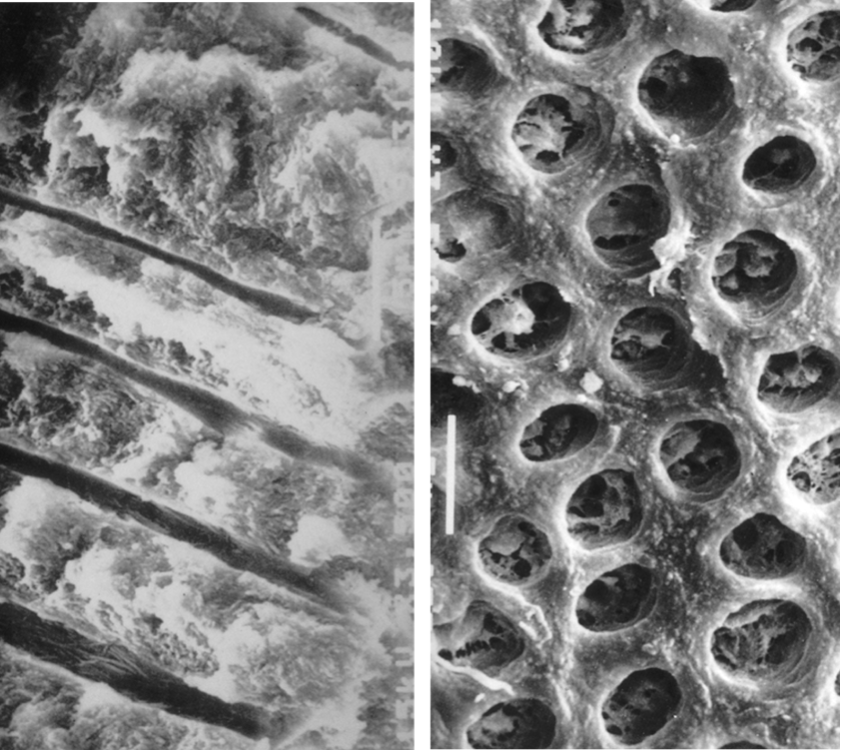

Fig. 2

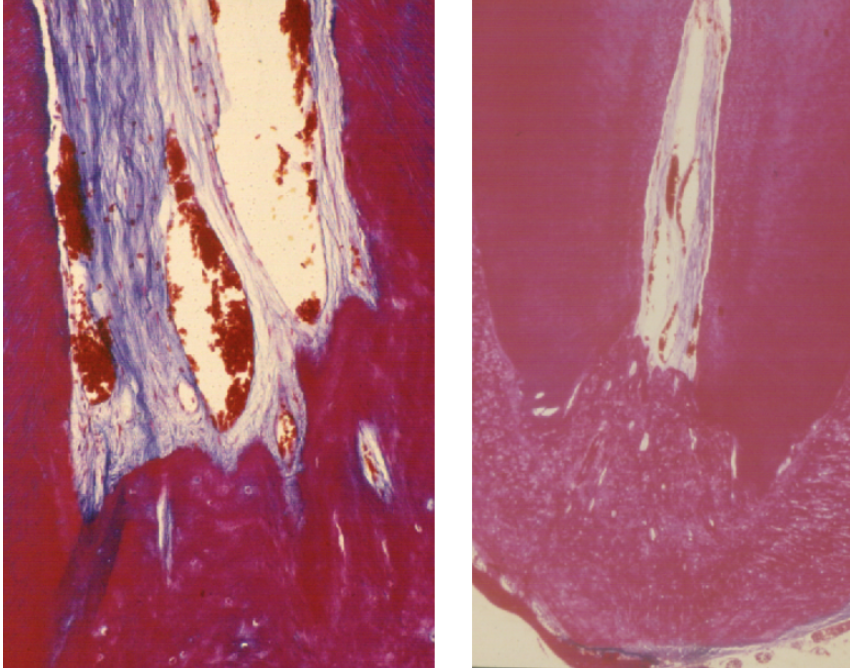

accessory canals

The accessory canals are lateral ramifications external to the root canal system that connect the neurovascular system of the pulp to that of the periodontal ligament. They can be present at any level of the root (Fig. 7.1a–f). These accessory canals contain connective tissue and blood vessels that connect the circulatory system of the pulp to that of the periodontium.

Estimations indicate that the prevalence of accessory canal systems is around 27% , 17% of which in the apical third of the root, about 9% in the middle third, and less than 2% in the coronal third. The furcation area of pluriradiculated teeth is an anatomical area that is more interested by accessory canals; the incidence of these can vary from 23% to 76%. In 2005, Vertucci distinguished various directions in which the accessory canals enter the furcation of the lower molars.

Although numerous clinical observations have shown the existance of this condition, the incidence of endodontic lesions in the marginal periodontium, deriving from accessory and furcation canals, appears to be low. Clearly, a large diameter of the accessory canals (up to 720 microns) corresponds to a higher probability of developing lesions.

Histology Courtesy of Prof. Massimo de Sanctis

Fig. 3

apical foramen

The apical foramen is the main means of communication between the pulp and the periodontium. Microbial catabolites and inflammatory substances can easily escape through the apical foramen to cause periradicular disease. The apex is also a potential gateway to the pulp for inflammatory products from deep periodontal pockets

Histology Courtesy of Prof. Massimo de Sanctis

Fig. 4

Etiology of endo-periodontal lesions

The fact that the periodontium and the dental pulp are anatomically interconnected also implies the possibility of an exchange of harmful agents in the opposite direction, i.e., from the environment outside the pulp to the pulp. A prerequisite for this condition is that the communication routes, which are normally protected by healthy periodontal tissue, become exposed (apical foramen, dentinal tubules, and accessory canals).

The effect of the periodontal disease on the pulp is a controversial topic, and numerous conflicting studies have been presented on the topic. According to some studies, the periodontal disease has no effect on the pulp, at least until it involves the apex. Other studies have shown an effect of the periodontal disease on the pulp that would lead to an increased calcification, collagen reabsorption, and an inflammatory state. However, the pulp does not seem to be severely impaired in teeth with a moderate attachment loss. As long as the microvascularization of the apical foramen remains intact, the pulp retains its vitality.

In addition to this concept, an important detail which should be emphasized is that there may be an influence of the periodontal therapy.

Although several animal studies support the hypothesis that subgingival cleaning procedures of pockets and/or roots do not threaten pulpal vitality, localized inflammatory changes may occur adjacent to instrumented root surfaces, followed by tissue repair in the form of hard tissue deposits on root canal walls.

Fig. 5

Assessment and diagnosis

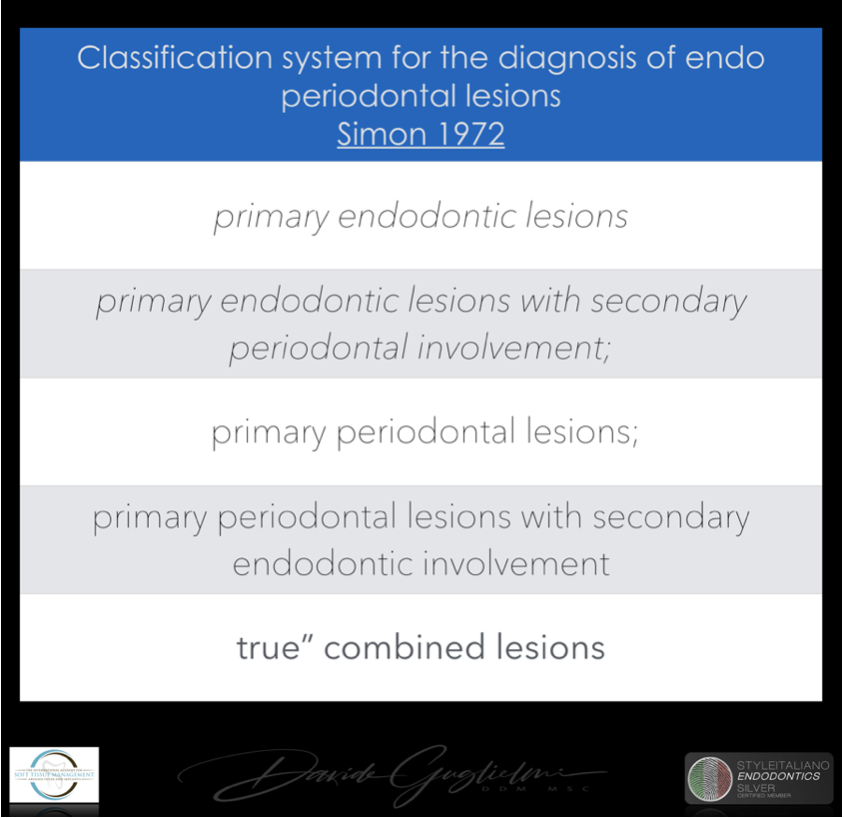

The classification system most commonly used for the diagnosis of endo periodontal lesions was published in 1972 by Simon et al. and included the following categories: (1) primary endodontic lesions; (2) primary endodontic lesions with secondary periodontal involvement; (3) primary periodontal lesions; (4) primary periodontal lesions with secondary endodontic involvement; and (5) “true” combined lesions.

The main drawback of this classification was that it based its categories on the primary source of infection (root canal or periodontal pocket). This seemed to be a suitable approach, as lesions of periodontal origin might have a worse prognosis than those of endodontic origin. Nonetheless, using the “history of the disease” as the main criteria for diagnosis was not practical, because in the majority of cases the complete history is unavailable to the clinician. In addition, determining the primary source of infection is not relevant for the treatment of endo-periodontal lesions, as both the root canal and the periodontal tissues would require treatment.

Thus, ideally, the diagnosis and classification of endo-periodontal lesions should be based on the present disease status and on the prognosis of the involved tooth, which would determine the first step of the treatment planning that would be whether to maintain or extract the tooth.

Fig. 6

Assessment and diagnosis

The first step in diagnosis should be to assess patient's history and clinical or radiographic examination. Patient history is important for identifying the occurrence of trauma, endodontic instrumentation or post preparation. If one or more of these events are identified, detailed clinical and radiographic examinations should be conducted to seek the presence of perforations, fractures, and cracking or external root resorption. Careful radiographic evaluation and clinical examination of the root anatomy is of great importance at this stage, to assess the integrity of the root and to help with differential diagnosis. A radicular groove, for example, might mimic a vertical root fracture in the radiograph.

If perforations and fractures are not identified the diagnosis should proceed to a second phase consisting of full‐mouth periodontal assessment, including probing depth, attachment level, bleeding on probing, suppuration and mobility, as well as tooth vitality and percussion tests. The presence of a periodontal pocket reaching or close to the apex combined with absence of pulp vitality would indicate the presence of an EPL.

That’s why the America Accademy of Periodontology and the European Federeration of Periodontology, during the Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri‐Implant Diseases and Conditions focused on different problems with this classification system: (1) grouping all Endodontic‐periodontal lesions under a single section entitled “Periodontitis Associated with Endodontic Lesion” was not ideal, as these lesions may occur in subjects with or without periodontitis; (2) the single category presented, “Combined Periodontal‐Endodontic Lesions”, was too generic and not sufficiently discriminative to help the clinician to determine the most effective treatment for a particular lesion.

Finally, Endodontic‐periodontal lesions should be classified according to signs and symptoms feasible to be assessed at the time in which the lesion is detected and that have a direct impact on their treatment, such as the presence or absence of fractures and perforations, presence or absence of periodontitis, and the extent of the periodontal destruction around the affected tooth.

I don’t know which classification could be more useful to the clinician but, as an Italian writer said “ai posteri l’ardua sentenza” (Manzoni A. - Il 5 maggio - 1821): it means the next generations will decide which one of these classifications will be the best.

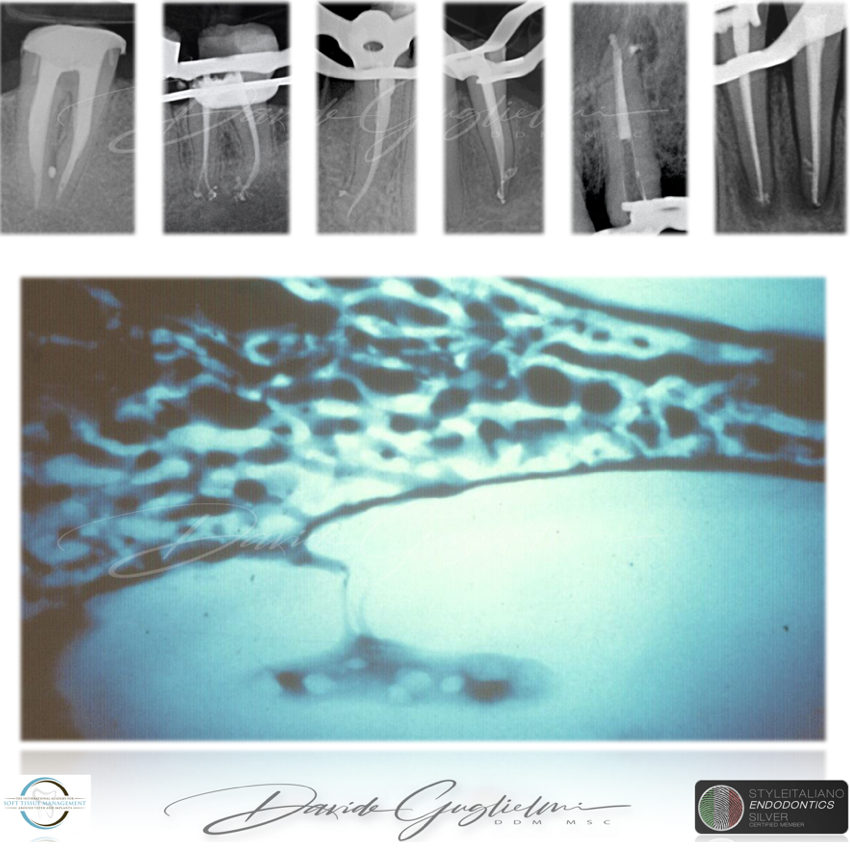

Fig. 7

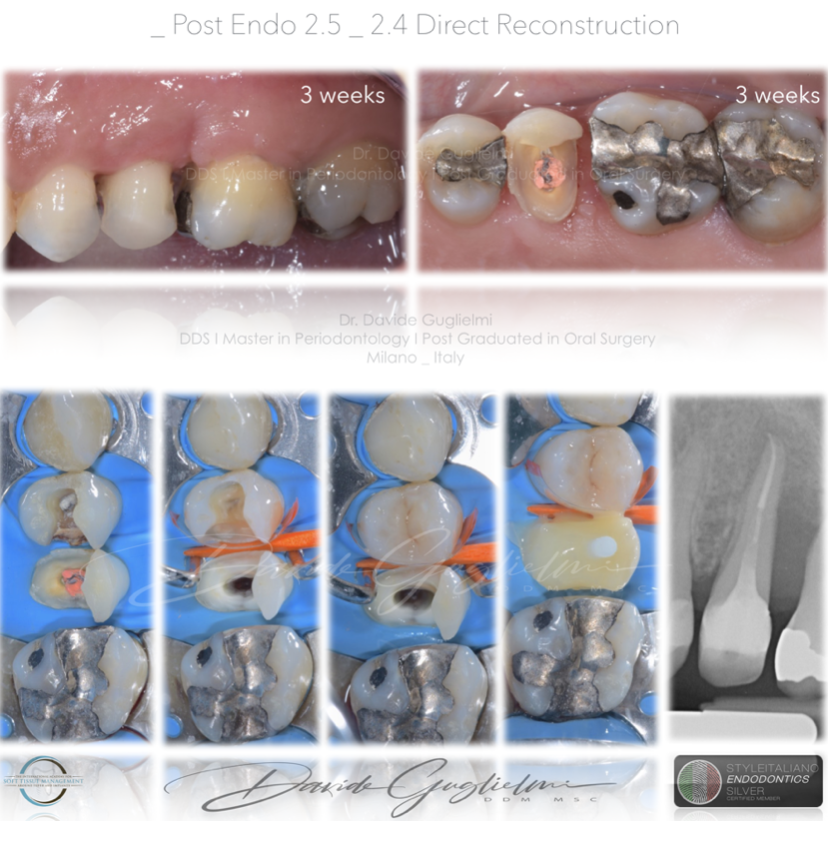

The case I want to show you is that of a 38-year-old girl, smoker (>10 cigarettes/day) without any systemic disease.

She came to my office with severe pain in the second quadrant.

A first examination revealed a periodontal abscess, swelling, plaque accumulation and a coronal fracture, given most likely by a large carious lesion on the tooth 2.5. In addiction, a periapical x-ray revealed two caries on adjacent teeth.

Diagnosis:

primary endodontic lesion (Simon 1972)

Grade 2 of endo-periodontal lesion without root damage in a non-periodontitis patient - (Herrera 2018)

Fig. 8

As we know, a chronic apical lesion in a tooth with necrotic pulp can, occasionally have an acute evolution, draining coronally through the periodontal ligament and thus reaching the gingival groove. This condition can clinically imitate the presence of a periodontal abscess. In primary endodontic lesions, the pulp is infected and its vitality is impaired.

In this patient, after anesthesia, a flap was raised with a 15C surgical blade in order to expose the cervical margin of the tooth, so to isolate correctly and to perform the root canal treatment.

Before suturing, an open flap debridement was performed on the adjacent teeth, but not on the distal surface of the element 2.5.

An antibiotic therapy was prescribed to the patient.

Fig. 9

After one week the sutures were removed and after 3 weeks (when the soft tissue healing was supposed to be completed) a direct reconstruction with a post was performed.

Fig. 10

At the 3 months follow up an x-ray and a periodontal chart were performed.

In all quadrants the PPD was <3 mm and the bone healing was quite evident from the x-ray.

At this point I proceeded with indirect adhesive therapy on the 2.6 (composite onlay) and the amalgam filling was polished.

Fig. 11

A fixed dental prosthesis was prepared, bonded and delivered to the patient.

Fig. 12

Clinical and radiographic images at 6 months of follow-up.

Fig. 13

Clinical and radiographic images before and after the therapy.

Conclusions

Endo-periodontal lesions are a core chapter in the formation of a dentist, since being able to identify, diagnose and treat them is part of the decision making process that leads to the creation of a correct treatment plan. Endodontum and peridontium, despite originated by different cells, are strictly connected: this is evident when we think that an endodontic pathology can have an effect on the periodontal health and vice-versa.

Bibliography

Rotstein, I. (2017). Interaction between endodontics and periodontics. Periodontology 2000, 74(1), 11–39.

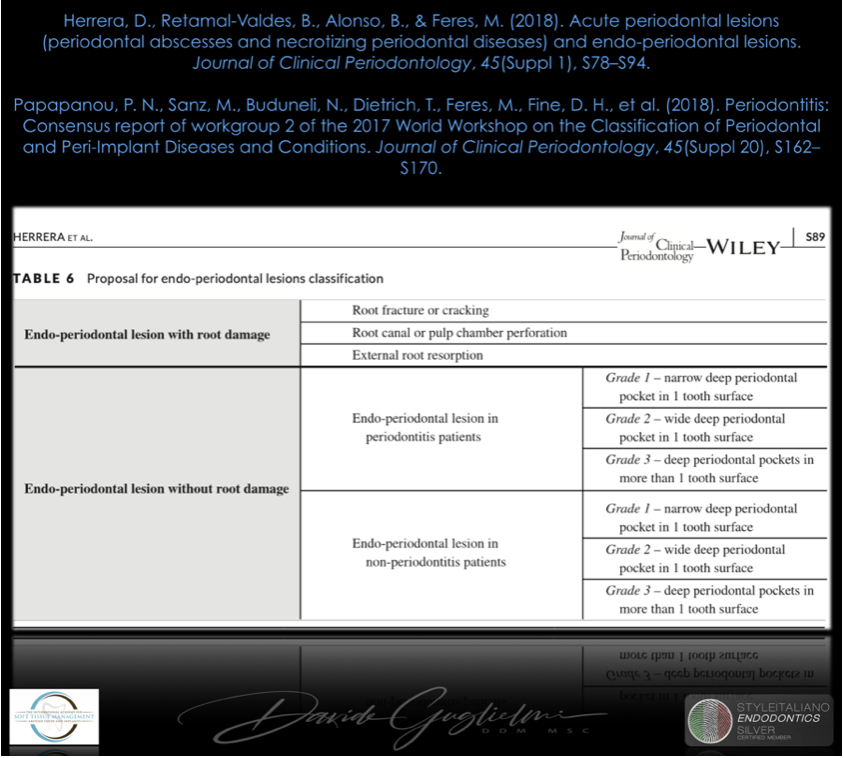

Herrera, D., Retamal-Valdes, B., Alonso, B., & Feres, M. (2018). Acute periodontal lesions (periodontal abscesses and necrotizing periodontal diseases) and endo-periodontal lesions. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 45(Suppl 1), S78–S94.

Papapanou, P. N., Sanz, M., Buduneli, N., Dietrich, T., Feres, M., Fine, D. H., et al. (2018). Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 45(Suppl 20), S162–S170.

Mjor IA, Nordahl I. The density and branching of dentinal tubules in human teeth. Archives of oral biology. 1996;41:401-12.

Kobayashi T, Hayashi A, Yoshikawa R, Okuda K, Hara K. The microbial flora from root canals and periodontal pockets of non-vital teeth associated with advanced periodontitis. Int Endod J. 1990;23:100-6.

Kobayashi T, Nonomura G, Watanabe LG, Marshall GWJ, Marshall SJ. Dentin tubule numerical density variations below the CEJ. J Dent. 2008;36:953-8.

De Deus QD. Frequency, location, and direction of the lateral, secondary, and accessory canals. J Endod. 1975;1:361-6.

Burch JG, Hulen S. A study of the presence of accessory foramina and the topography of molar furcations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974;38:451–5.

Gutmann JL. Prevalence, location, and patency of accessory canals in the furcation region of permanent molars. Journal of periodontology. 1978;49:21–6.

Goldberg F, Massone EJ, Soares I, Bittencourt AZ. Accessory orifices: anatomical relationship between the pulp chamber floor and the furcation. J Endod. 1987;13:176– 81.

Vertucci FJ. Root canal morphology and its relationship to endodontic procedures. Endo Topics. 2005;10:3-29.

Lindhe J, Nyman S, Lang NP. Treatment Planning. Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry. 4th Edition.

Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Company; 2003. p. 414-31.

Ricucci D, Siqueira JF, Jr. Fate of the tissue in lateral canals and apical ramifications in response to

pathologic conditions and treatment procedures. J Endod. 2010;36(1):1-15.

Seltzer S, Bender IB, Ziontz M. The interrelationship of pulp and periodontal disease. Oral Surg Oral Med

Oral Pathol. 1963;16:1474–90.

American AAOE. Glossary of endodontic terms. 8th ed. Chicago: Association of Endodontists; 2012.

de Sanctis M, Goracci C, Zucchelli G. Long-term Effect on Tooth Vitality of Regenerative Therapy in Deep

Periodontal Bony Defects: A Retrospective Study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2013;33(2):151-7.

Mandi FA. Histological study of the pulp changes caused by periodontal disease. J Br Endod Soc.

1972;6:80-2.

Adriaens PA, Edwards CA, De Boever JA, Loesche WJ. Ultrastructural observations on bacterial invasion in

cementum and radicular dentin of periodontally diseased human teeth. J Periodontol. 1988;59:493-503.

Rotstein I, Simon JHS. The endo-perio lesion: a critical appraisal of the disease condition. Endo Topics.

2006;13:34–56.

Tosco, E. (2017). Le lesioni endo-parodontali. Il Dentista Moderno, 1–15.

Gagliani M, Gorni GM F, Bertani P et Al 2019 - Retreatments - EDRA