Transforming a Non-Visible Separated File into a Visible Fragment: A Conservative Retrieval Approach

05/01/2026

Abdullah AboHalima

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

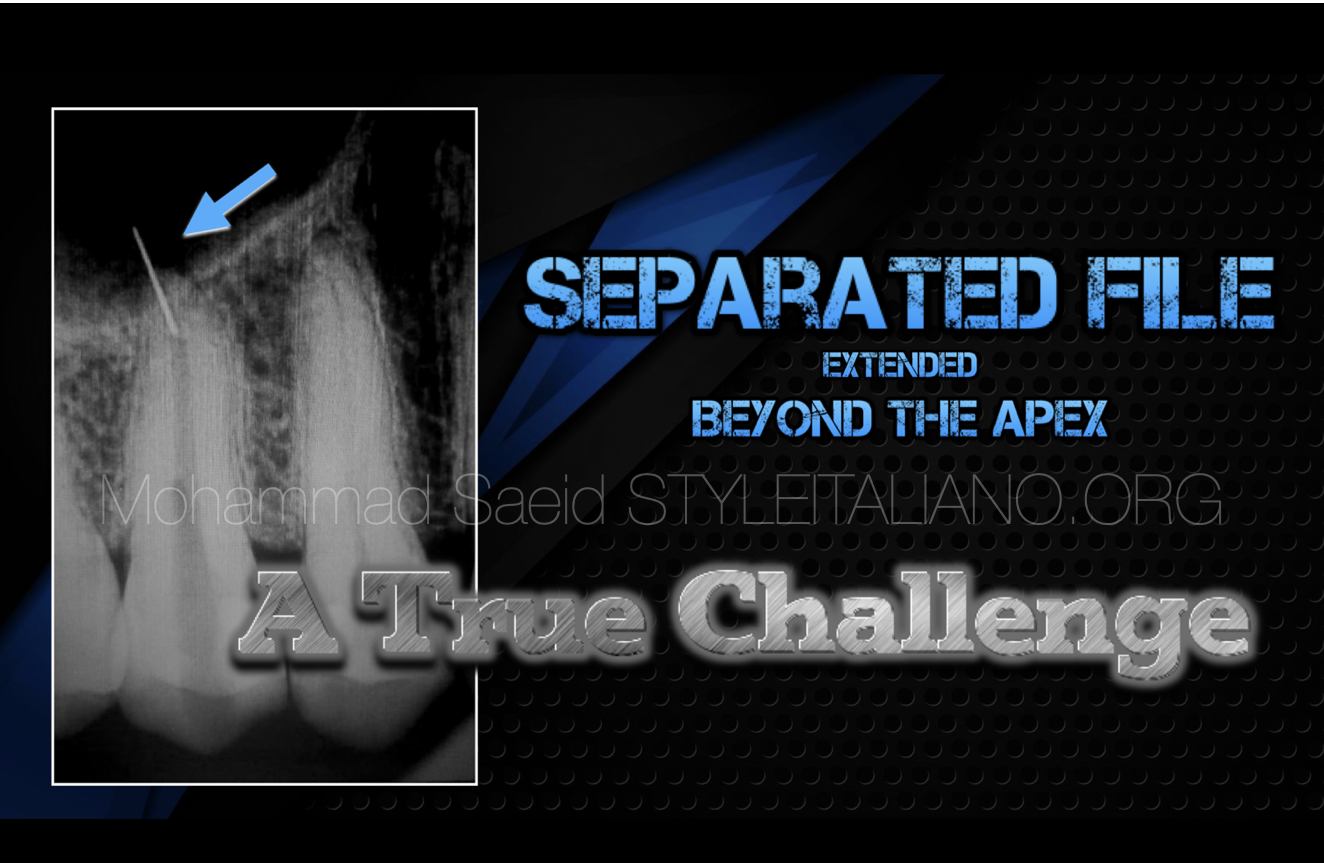

Separated instrument one of the most challenging complications in endodontic practice. While some fractured instruments can be easily visualized and managed, others remain hidden, particularly those located beyond canal curvatures posing a far greater clinical challenge.

The inability to directly visualize the fragment, increasing the risk of excessive dentin removal, perforation, or structural weakening if retrieval is attempted blindly.

Today’s endodontic philosophy emphasizes that the objective is not merely the removal of the fractured fragment, but the preservation of long-term tooth restorability.

Successful retrieval of a separated instrument depends on careful case selection, strategic planning, and conservative dentin management. This article presents a clinical approach for converting a non-visible separated instrument into a visible and retrievable fragment through controlled dentin modification and enhanced visualization, ensuring a safe and predictable outcome.

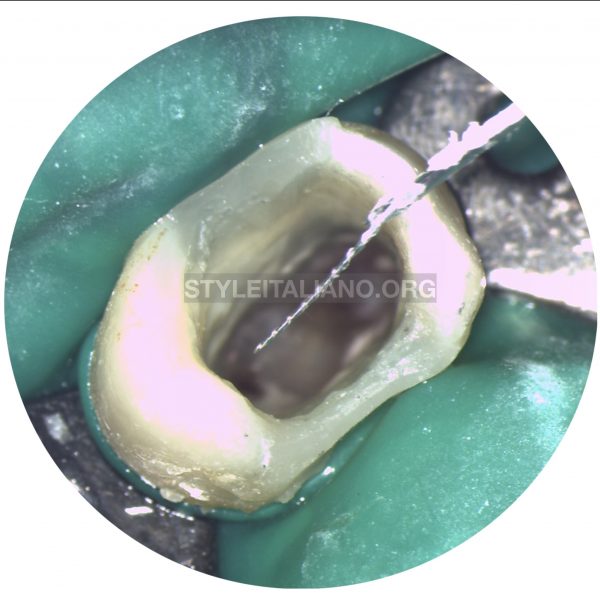

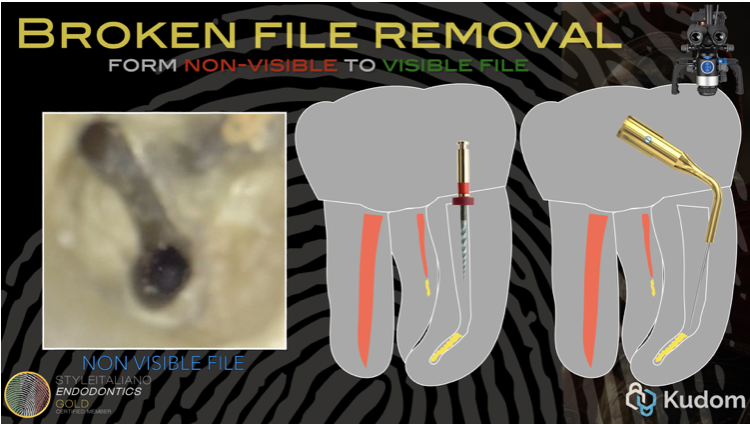

Fig. 1

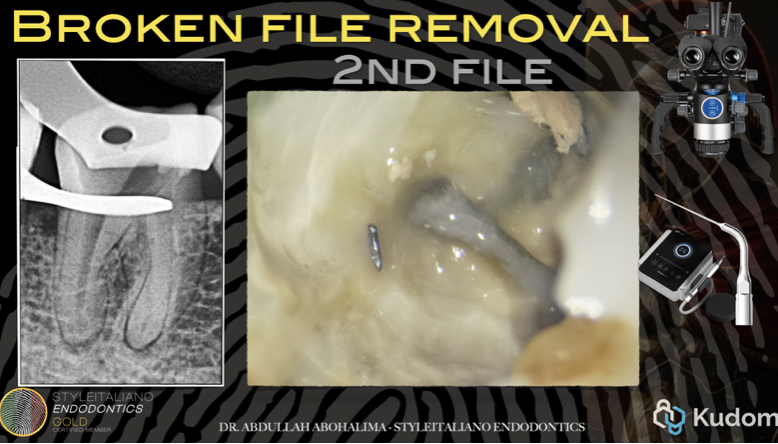

This patient came with two broken files: one in the ML canal, which was short and relatively easy to remove, but the canal underneath was very narrow and blocked. The other one was in the MB canal, and this was much harder, because the file was fractured beyond the curve, which made it a non-visible file.

To properly address this clinical situation, appropriate case selection is essential.

Not every separated instrument should be attempted for removal; the decision must be guided by clinical judgment, operator skill, and a clear understanding of anatomical limitations.

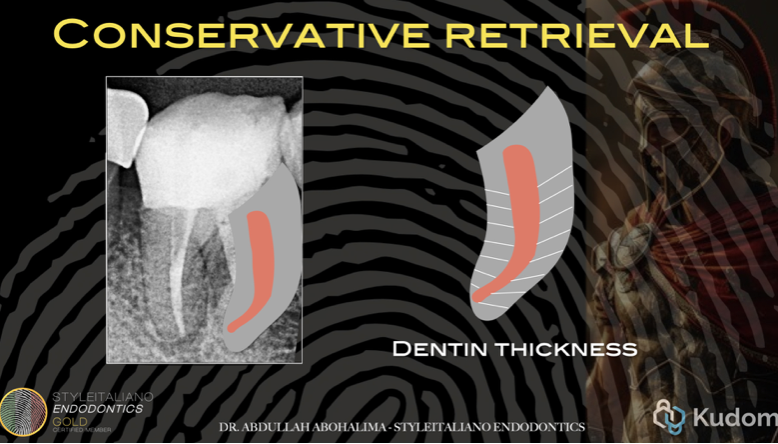

As demonstrated in the CBCT, there is sufficient remaining dentin thickness surrounding the fragment in both the mesiodistal and buccolingual dimensions.

This favorable anatomy allows safe dentin modification from the inner wall while maintaining a conservative approach and minimizing structural compromise.

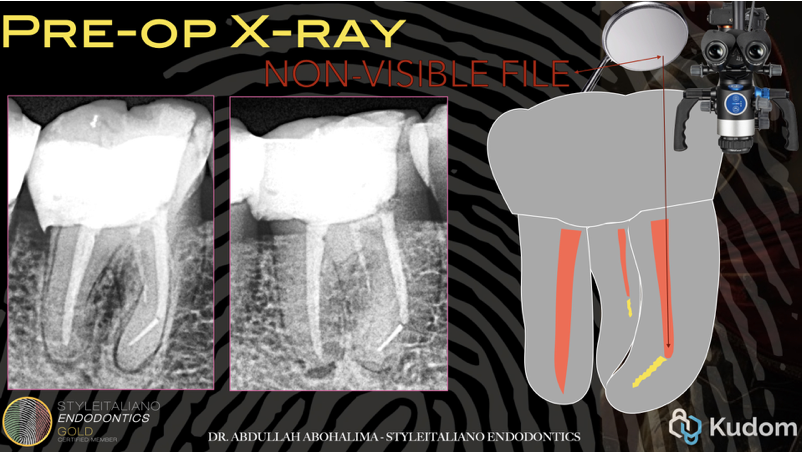

The first and most important step in cases like this is to assess restorability before even thinking about how to remove the broken file.

This requires removing all the old restorations and caries until sound tooth structure is reached, enabling proper bonding, and then evaluate whether I already have a ferrule, or if crown lengthening will be required —either now or later—before doing the pre-endo build-up.

The first step is to remove the gutta-percha from inside the canal.

The separated instrument will not be visible at this stage, as it is located beyond the curvature.

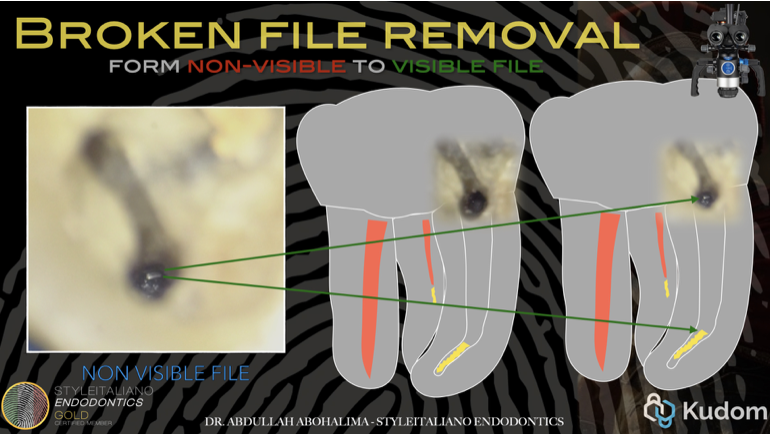

Fig. 2

Coronal flaring was first performed on the outer wall, which provided two key advantages:

• Improved light access, allowing clearer visualization of the canal.

• Additional space to introduce a pre-bent ultrasonic tip and facilitate controlled troughing along the inner wall.

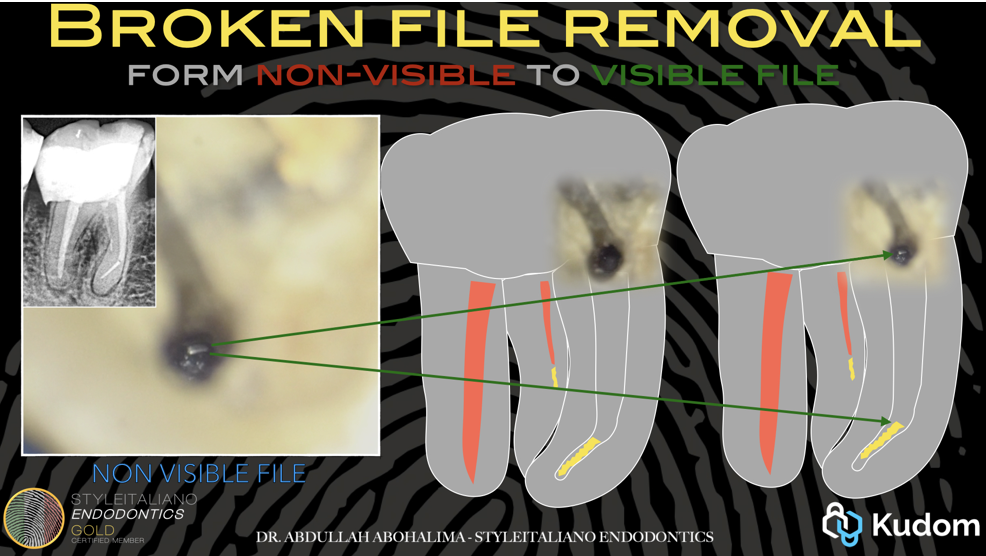

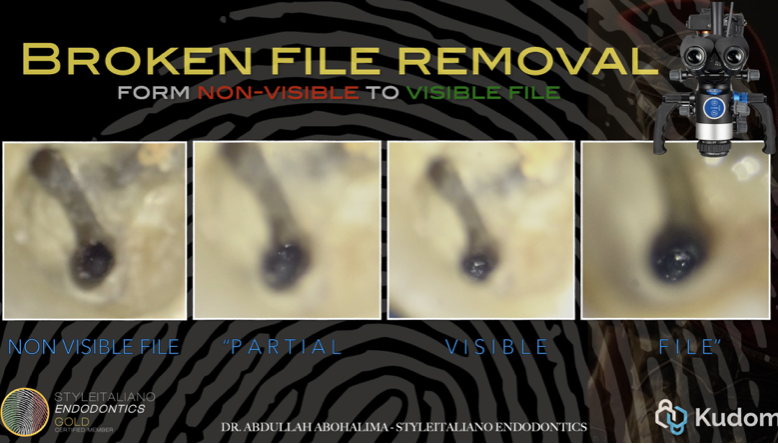

Fig. 3

The next step involved using a small pre-bent ultrasonic tip directed toward the inner wall, carefully navigating between the fractured fragment and the canal wall. Coronal flaring was then carried out on the inner wall, gradually exposing the fragment—from non-visible, to partially visible, and eventually fully visible—while maintaining a conservative approach and preserving as much dentin as possible.

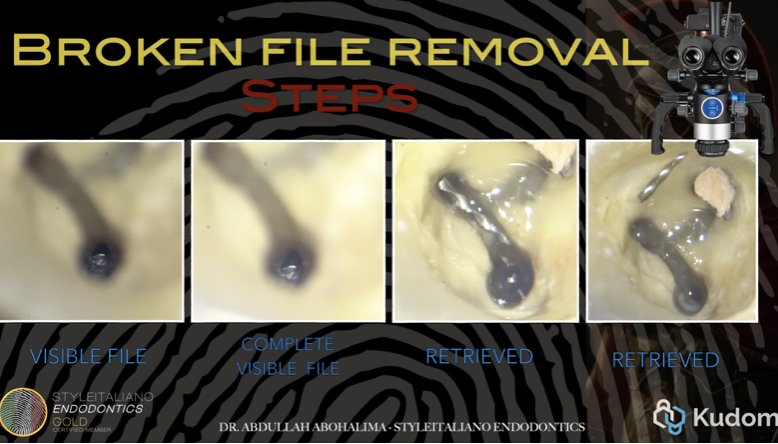

Fig. 4

Once the inner wall had been gently troughed and the coronal portion of the fragment was exposed, further pre-bending of the ultrasonic tip was performed, followed by creating a 90° trough preparation, until the fragment became fully visible.

Clinical video demonstrating the step-by-step retrieval of a non-visible separated instrument, illustrating the process of gradually converting the fragment from non-visible to fully visible and ultimately removing it safely. Each stage highlights key techniques, including coronal flaring, careful troughing, pre-bending of ultrasonic tips, and conservative dentin management to ensure predictable and safe outcomes.

Fig. 5

Sequential steps for separated file retrieval

Fig. 6

Management of the mesiolingual (ML) canal file was also successfully achieved.

Fig. 7

master cone after canal shaping, clearly demonstrating that the two mesial canals are completely separate from each other.

Fig. 8

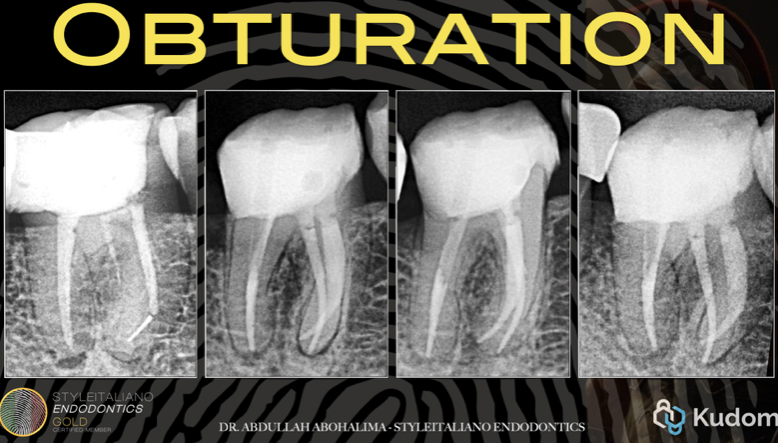

Moving on to obturation, it is important to pause and revisit a key principle discussed before starting the case the indications and limitations of file retrieval.

Comparison of pre-operative and post-operative radiographs demonstrates a conservative approach: both fractured files were successfully removed, and the canals were shaped while preserving tooth structure.

Fig. 9

Despite performing coronal flaring and inner wall troughing, sufficient dentin thickness was preserved, owing to proper case selection from the outset.

The outlines of the gutta-percha and the root are clearly visible, confirming adequate remaining dentin and uniform canal shaping without over-troughing in any specific area.

Conclusions

Non-visible separated instruments should not be approached as a retrieval problem alone, but as a decision-making challenge rooted in anatomy and restorability.

Creating visibility through controlled dentin modification transforms a high-risk situation into a manageable one, allowing ultrasonic techniques to be applied safely and predictably.

Accurate case selection, respect for root anatomy, and a conservative mindset remain the foundation for successful management of separated instruments.

Bibliography

1.Terauchi Y, Sexton C, Bakland LK, Bogen G. Factors Affecting the Removal Time of Separated Instruments. J Endod. 2021 Aug;47(8):1245-1252. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2021.05.003. Epub 2021 May 14. PMID: 34000326.

2.Ruddle CJ: Ch. 25, Nonsurgical endodontic retreatment. In Pathways of the Pulp, 8th ed., Cohen S, Burns RC, eds., St. Louis: Mosby, pp. 875-929, 2002

3. Ruddle CJ. Cleaning and shaping root canal systems. In: Cohen S, Burns RC, editors. Pathways of the Pulp. 8 th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2001. p. 231-91.

4. Fors UG, Berg JO. Endodontic treatment of root canals obstructed by foreign objects. Int Endod J 1986;19:2-10.

5.Madarati AA, Hunter MJ, Dummer PM. Management of intracanal separated instruments. J Endod. 2013 May;39(5):569-81. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.12.033. Epub 2013 Mar 15. PMID: 23611371.

6. Hülsmann M. Removal of fractured instruments using a combined automated/ultrasonic technique. J Endod 1994;20:144-7.

7. Ruddle CJ. Nonsurgical endodontic retreatment. In: Cohen S,

Burns RC, editors. Pathways of the Pulp. 8 th ed. St Louis, Mo:

Mosby; 2001. p. 875-929.