Management of broken files - A clinical approach

30/06/2017

Zaher Al-taqi

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /var/www/vhosts/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/endodontics.styleitaliano.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /var/www/vhosts/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/endodontics.styleitaliano.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

You have a great day and you feel very relaxed while doing an endo treatment for a lower molar, everything is going well, the pulp chamber was opened correctly in a conservative manner, you found all the root canals while correctly following the floor map, then starting instrumentation, shaping, and cleaning procedures; you feel that you are playing a winning game for your side, the blades of your rotary files are pretty sharp and cutting the dentine feels like a knife cutting butter. Suddenly, your rotary file continues to spin effortlessly, you get some shrinkage in your stomach: you stop, pull the file out, and notice that your 25 mm file is now measuring 20 mm, Verification via radiograph confirms that you have a separated file inside the canal and now you have to tell the patient that he has a separated file in his tooth...

NOW WHAT???

How will you manage that?

Fracture of endodontic instruments in a root canal is an unfortunate occurrence that may hinder the root canal procedure and negatively impact the endodontic treatment outcome. Fracture of an instrument itself may not cause treatment failure. However, fragments present in the root canal can prevent proper preparation of root canal space. The overall endodontic prognosis following instrument separation is likely to depend on the stage and degree of canal preparation and disinfection at the time of the instrument fracture: the main prognostic factor in such cases is reported to be the existence or non-existence of a preoperative periradicular pathosis.

Historically, it was recommended to leave the fractured instrument in the canal as it will not affect the prognosis and could be retained as the risk of removal was very high (1, 2). However, these publications came before the use of dental microscope and the introduction of specialized ultrasonic tips to manage the broken files, which would limit the risk of complications. So, recently we have 2 options regarding the fractured instrument:

- Bypassing

- Removal

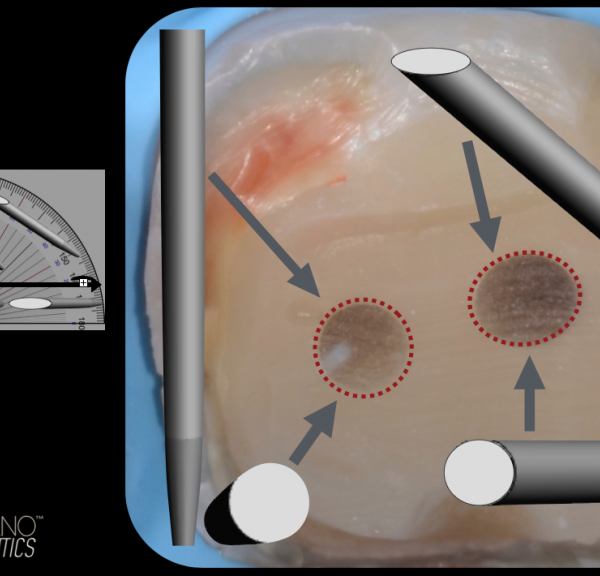

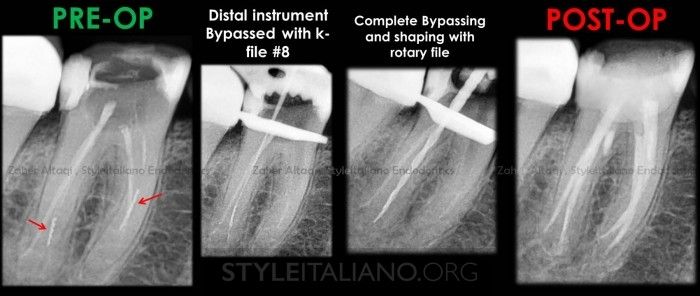

Fig. 1

BYPASSING THE FRACTURED INSTRUMENT

Bypassing technique is considered more conservative regarding the amount of dentine removal when compared to removal techniques especially if the fragment is located in the apical one third or beyond the canal curvature. It has been reported that if the file is bypassed, the obturation quality is not compromised (3). This technique depends on locating or catching a tiny space behind the broken instrument with precurved small k-file (6,8,10) in a watch-winding motion associated with EDTA gel to facilitate the task; the moment when you catch that space and your k-file is engaged there, we can start some picking motion along with watch-winding motion till we reach the apex, bypassing should be done till size 20 or 25 k-file (Multiple Radiographs should be done to confirm bypassing after each file size). Then, we have two choices to complete the shaping, either with manual files and step-back technique or with rotary files, but its slightly risky (small taper is preferable here, usually 4% is enough to manage a good obturation for the root canal system). After complete shapin, activation of irrigant solutions with ultrasonic tips behind the broken file may lead to its removal if you are lucky.

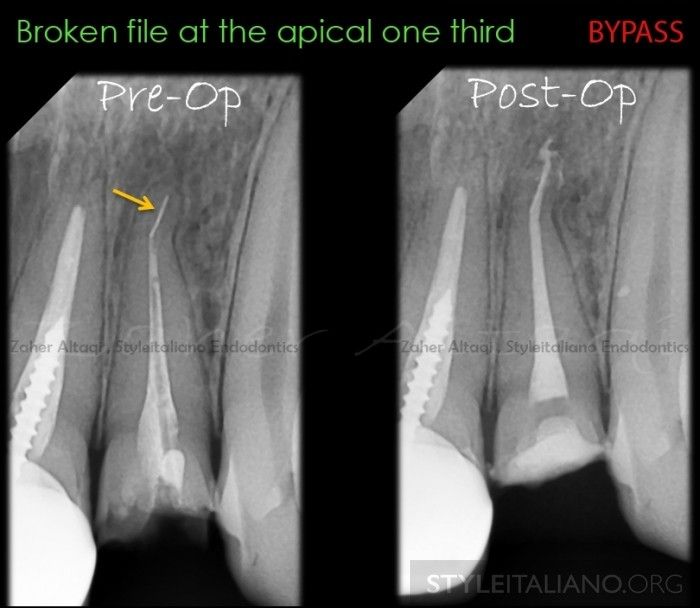

Fig. 2

FRACTURED INSTRUMENT REMOVAL

It has been reported that, in the presence of a periapical lesion, endodontic treatment which is compromised by mishaps and errors – such as a broken instrument – demonstrated reduced healing (4). Obviously, removal of a broken file will facilitate correct working length control (assuming there is minimum canal curvature), shaping and effective obturation of the root canal system (5). The likelihood percentage of instrument removal by clinicians raging from 53% to 95% (6,7). The wide percentage variation of these results can be due to many factors influencing broken instruments removal, such as:

1) Location, length, type and material of fractured instrument

2) Tooth/canal involved

3) Clinician’s skills and available armamentarium (Microscope, ultrasonics and other devices designed for instrument removal)

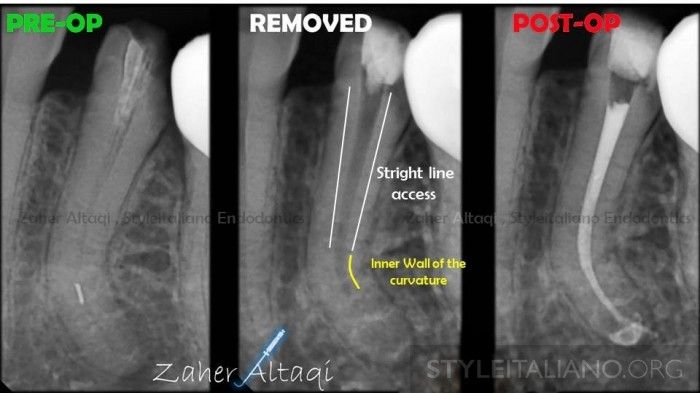

Fig. 3

METHODS FOR REMOVAL

There is a wide variety of techniques available to facilitate instruments removal. These techniques can be chategorized as:

1) Ultrasonics technique

2) Grasping techniques, such as microtube devices, loop, micro tweezer, pliers/forceps ( that will be discussed in the second part 2 of this article)

There is no one removal technique or device that can be used for all fractured instrument cases, each case should be well assisted before choosing the removal technique.

The success of certain devices has been well documented in the case of ultrasonic removal (5,8) but, unfortunately, many of the microtube systems have no such scientific evaluation; this presents problems for clinicians in assessing their relative efficacy.

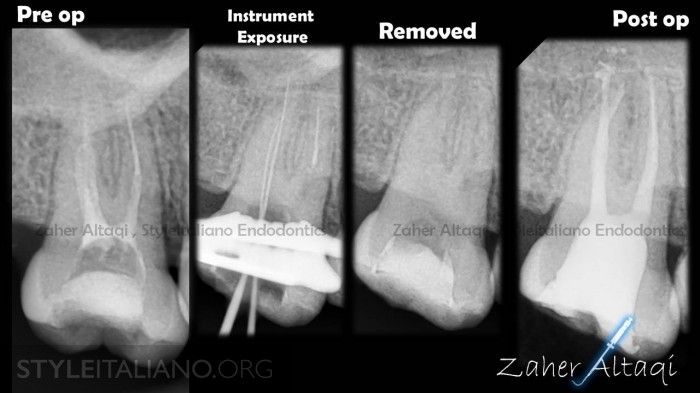

Fig. 4

A) ULTRASONIC REMOVAL TECHINQUE

1) Radiographic evaluation (instrument location, length, curvature); CBCT provides good assessment for such cases.

2) Instrument Exposure (straight line access to the instrument with GG.2, 3 without modification to preserve more tooth structure, or with large size rotary files until the instrument become visible under the microscope)

3) Very thin ultrasonic tips should be used to disengage the instrument: ultrasonic preparation should be done only on the inner wall of the curvature or the root (9) .

4) After ultrasonic preparation, irrigant solution such as EDTA can be used with ultrasonic activation to facilitate instrument removal into the pulp chamber.

– Follow the clinical images description of this case step by step –

Fig. 5

After removal of old guttapercha, the instrument was exposed by GG.3 and become visible under microscope (second image).

Ultrasonic preparation to create a space and disingage the instrument from the dentine walls (third image)

NOTE: ultrasonic preparation was only done on the inner wall of the root without counter-clockwise preparation to preserve more dentine (check the post-op X-ray in the previous image)

Fig. 6

Upper 7th with two separated instruments in the middle third of the distal canal, the two instruments were removed successfully with help of magnification and ultrasonics. After preparing a small space on the inner wall, EDTA solution was used with ultrasonic activation to facilitate the files removal toward the pulp chamber.

Fig. 7

NOTE: the ultrasonic preparation of the space on the inner wall ( second image,yellow arrow)

Fig. 8

Lower molar with two broken files, one in the MB canal and the other one in the DB root.

The mesial one was removed with the same technique described previously. The distal one is deeper apically so, bypassing could be helpful here without sacrificing too much dentine structure to remove it. The instrument was bypassed after many attempts with small K-files (6,8) till size #25. Then complete shaping with rotary files carefully.

In this case there was a furcal perforation which was repared with MTA (note the post-op X-ray and the clinical images).

Fig. 9

Clinical images of the previous case: initial, broken file removed, MM was located, Perforation was repaired with MTA , obturation was done with CWC technique.

Fig. 10

When the broken instrument is located beyond the root canal curvature, it is difficult to observe the coronal part of the instrument under the microscope, but with a precurved, thin ulrasonic tip placed to the inner wall of the curvature and preparing a small space on that wall the instrument can be removed.

Conclusions

Fractured instruments can be removed successfully by a variety of methods such as fine ultrasonic tips. Microscopic magnification is essential to remove a broken file from inside a root canal. As removal of a fractured file is associated with considerable risk, bypassing the fragment should be also considered.

Bibliography

Crump M C, Natkin E. Relationship of a broken root canal instrument to endodontic case prognosis: a clinical investigation. J Am Dent 1970; 80: 13411347.

Fox J, Moodnik R M, Greenfield E, Atkinson J S. Filling root canals with files: radiographic evaluation of 304 cases. N Y State Dent J 1972; 38: 154157.

Saunders J, Eleazer P, Zhang P, Michalek S. Effect of a separated instrument on bacterial penetration of obturated root canals. J Endod 2004; 30: 177179.

de Chevigny C, Dao T T, Basrani B R et al. Treatment outcome in endodontics: the Toronto study-phase 4. J Endod 2008; 34: 258263.

Ward J R, Parashos P, Messer H H. Evaluation of an ultrasonic technique to remove fractured rotary nickel-titanium instruments from root canals: clinical cases. J Endod 2003; 29: 764767.

Hülsmann M, Schinkel I. Influence of several factors on the success or failure of removal of fractured instruments from the root canal. Endod Dent Traumatol 1999; 15: 252258.

Suter B, Lussi A, Sequeira P. Probability of removing fractured instruments from root canals. Int Endod J 2005; 38: 112123.

Souter N J, Messer H. Complications associated with fractured file removal using an ultrasonic technique. J Endod 2005; 31: 450452.

Terauchi Y, O'Leary L, Suda H. Removal of separated files from root canals with a new file removal system: case reports. J Endod. 2006;32:789-797