The vicious cycle of errors in retreatment cases

18/04/2024

Marc Kaloustian

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

During primary treatment, even in simple cases, many root canal anatomy alteration and errors can occur such as access cavity over enlargement, perforations, blocages or file breakage (Ruddle CJ, 2004). Sometimes, many iatrogenic issues combine and complicate the decision making (Gulabival K & al. 2023). Central incisors retreatments are particular because of the esthetic aspect of these teeth that will motivate the practitioner and the patient to try to keep them for as long as possible in a patient’s mouth.

This case study will analyze a case of an upper left central incision retreatment with many technical errors such as a buccal perforation done during access preparation without taking care of the tooth rotation, a separated file in the middle part of the canal, another lateral mesial perforation that occurred after an unsuccessful trial of bypassing the instrument and an apical blockage.

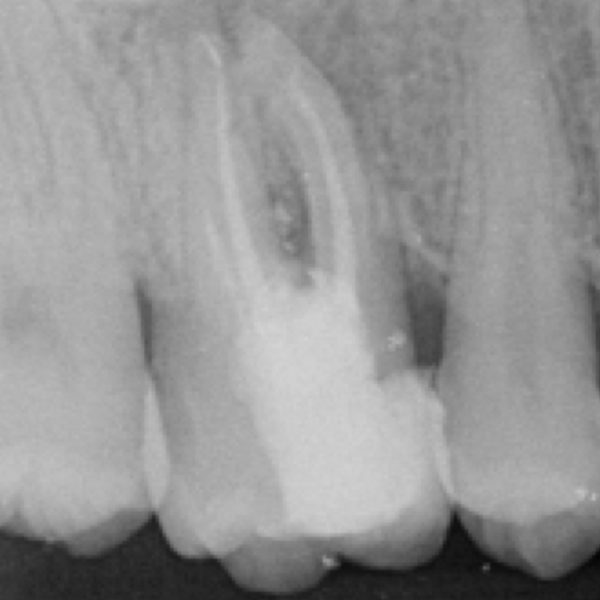

Fig. 1

Upon radiographic preliminary examination, an upper left central incisor reveals poor mesial and distal composite restorations, a temporary palatal filling, a short obturation with a separated filed in the coronal third of the canal and a lateral perforation poorly filled with an excess of material in the peri-apical tissues.

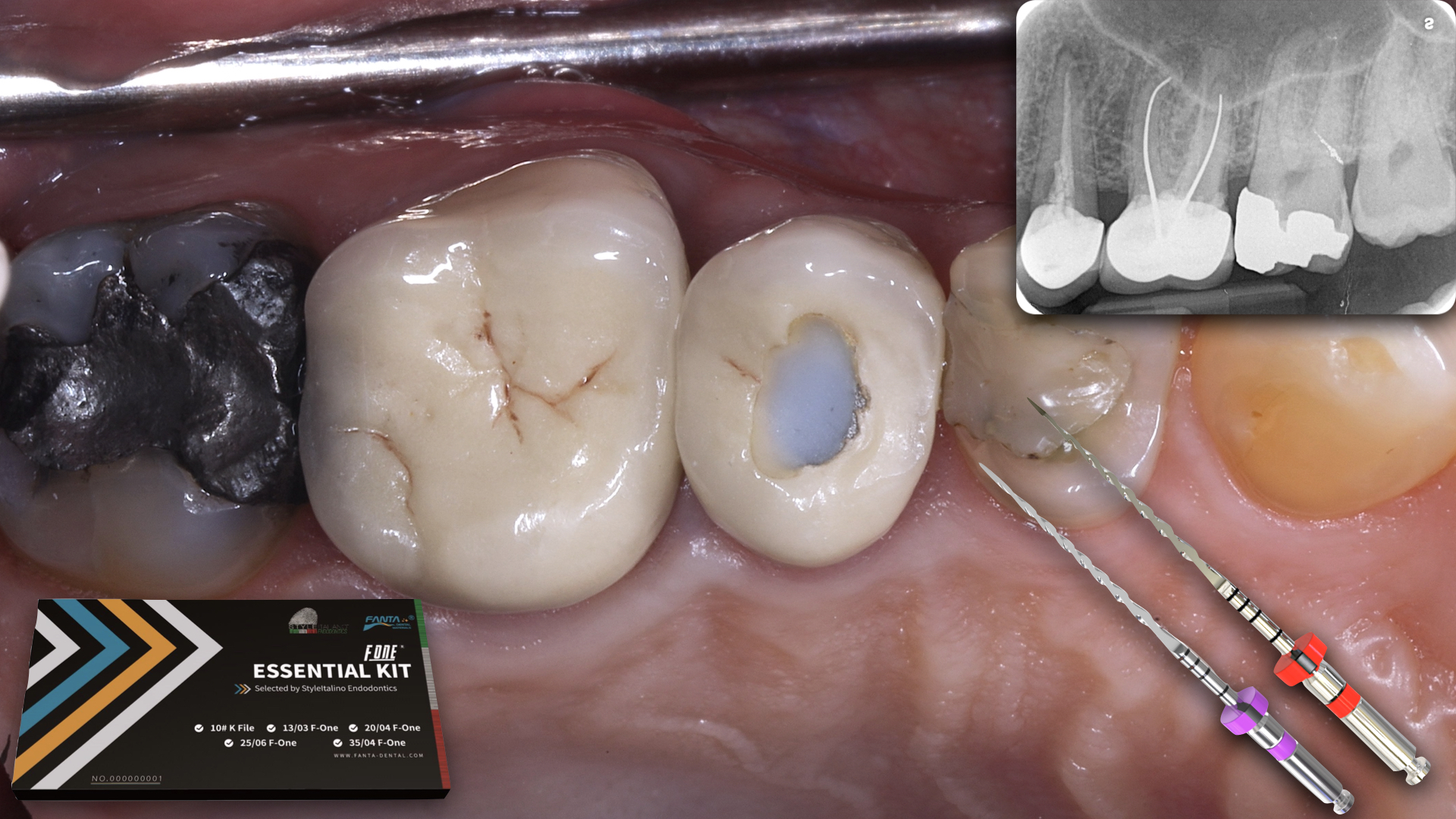

After the elimination of the temporary filling material, the first step of the retreatment procedure was to remove safely the remnants of GP surrounding the separated instrument using a gates Glidden 3.

An additional removal of filling material was done using a rotary file and an Ultrasonic tip.

The instrument was localized under magnification X16, an ultrasonic tip was activated to remove conservatively and selectively dentin to expose completely the head of the broken file. Afterwards, an explorer was used to displace the instrument for a better grasping and retrieval.

Fig. 2

The visualization of the instrument after the use of the ultrasonic tip and the explorer.

After abundant irrigation for optimal removal of debris, the instrument was retrieved using the grasping loop technique, BTR with a 0.5 wire (Terauchi Y & al. 2022).

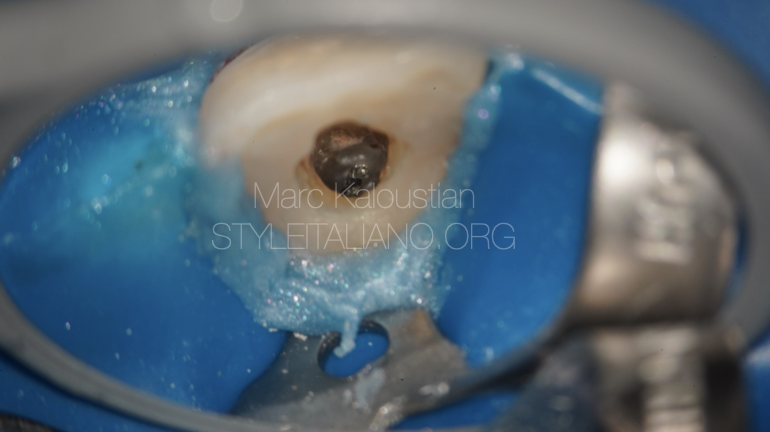

Fig. 3

Instrument of 10 mm length retrieved.

The canal was blocked with debris during the primary treatment. A C Pilot 25 mm file was used with a watch winding motion and light pressure to gain patency.

The working length was recorded with a 31 mm 10 K file using the Findex apex locator.

Fig. 4

A periapical xray was done to confirm the working length.

The shaping was performed with a single file 25/06 (Endostar E3 Azure, Potent) operated with Optimum Torque Reverse mode at 500 RPM.

The irrigation was done with 12 ml of NaOCL 5.25 %, The canal was dried with a micro-canula and EDTA 17% was placed inside the canal for 1 mn. A final rince with sterile water was done to eliminate the EDTA. The irrigation was activated with a sonic device , the EndoActivator (Dentsply Sirona) with the 25/04 tip, for one minute inside the canal.

After shaping and cleaning, removal of gutta percha remnants, an observation under magnification showed the presence of another perforation in the buccal aspect of the tooth, that occurred during the access cavity preparation of the primary treatment.

Fig. 5

A Fine Medium cone (Coltène Whaledent, Langenau, Germany) was selected at working length with a proper tug back.

The obturation of the canal was done with the injection of a bioceramic sealer (NeoSealer, avalon) and a single cone technique. An additional cone was added to prevent voids.

Fig. 6

The cones were cut below the buccal perforation, at the same level of the lateral perforation.

The access cavity and both perforations were cleaned with an ultrasonic tip and dried with a micro-succion canula and sterile paper points.

The lateral perforation and the buccal perforation were filled with bioceramic Putty material (NeoPutty, Avalon) using the MapOne carrier (Produits Dentaires, Vevey, Switzerland). Pluggers, paper points and micro brush were used for light compaction. (Said SM & al. 2016)

Fig. 7

A teflon and temporary filling was placed at the end of the first session. The xray shows the main canal obturation and the repair of the buccal and lateral perforations.

At the second session, the complete setting of the bioceramic was checked using a sharp explorer.

The access cavity was filled with a composite material.

Fig. 8

The final Xray shows the obturation of the main canal, the perforations and the composite on all coronal walls. The patient was advised to proceed with a full coverage restoration at the referring dentist.

Conclusions

In cases of retreatment with multiple errors, a good decision making and proper assessment of the case is necessary. Newly done perforations with small diameter and the absence of lesion will increase the prognosis of the treatment (Gorni FG & al. 2022)

The treatment workflow is also very important with a step by step correction of each error. The closure of perforation is often advised prior to the main canal preparation and filling, but in this particular case, the presence of a separated file that should be retrieved, lead us to first deal with the canal and fill it underneath the perforation and then take care of the lateral and buccal perforations.

Usually it is always preferable to seal the coronal part at the same session. However, in cases of a perforation, it is advisable to postpone the build up after verifying the good setting of the 2 perforation repair materials.

Bibliography

- Gorni FG, Ionescu AC, Ambrogi F, Brambilla E, Gagliani MM. Prognostic Factors and Primary Healing on Root Perforation Repaired with MTA: A 14-year Longitudinal Study. J Endod. 2022 Sep;48(9):1092-1099. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2022.06.005.

- Gorni FG, Gagliani MM. The outcome of endodontic retreatment: a 2-yr follow-up. J Endod. 2004 Jan;30(1):1-4. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200401000-00001.

- Gulabivala K, Ng YL. Factors that affect the outcomes of root canal treatment and retreatment-A reframing of the principles. Int Endod J. 2023 Mar;56 Suppl 2:82-115. doi: 10.1111/iej.13897.

- Saed SM, Ashley MP, Darcey J. Root perforations: aetiology, management strategies and outcomes. The hole truth. Br Dent J. 2016 Feb 26;220(4):171-80. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.132.

- Terauchi Y, Ali WT, Abielhassan MM. Present status and future directions: Removal of fractured instruments. Int Endod J. 2022 May;55 Suppl 3:685-709. doi: 10.1111/iej.13743. Epub 2022 Apr 18.