Little molars

19/08/2023

Fellow

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

The presence of 3 rooted premolars called, little molars, is pretty infrequent. Found in only 1-4% of cases with regional variation. The two morphological types involve either two buccal and one palatal root or two palatal and one buccal root. Managing these cases is demanding due to the rarity and challenges in diagnosis, access, instrumentation, and restoration. Diagnosing without CBCT imaging can be difficult. Precise conservative access, cautious instrumentation, and a minimally invasive approach using minimally invasive instruments are crucial for effective treatment.

Every experienced endodontist dreams of having a three-rooted premolar in their endodontic portfolio. What causes this anatomical variation to be so desirable? Above all, it's a very rare occurrence. According to a literature review, the prevalence of three-rooted premolars, also known as "miniature molars," ranges between 4% and 1% for first premolars and below 1% for second premolars. Interestingly, the prevalence of "small molars" varies across different populations and countries. According to some studies, the average prevalence of three-rooted cases ranged from 0.4% to 9.2%. In the USA, it accounted for 6% to 4% (Carns and Skidmore, 1973; Vertucci, 1984). In Brazil, it ranged from 3.5% to 2.5% (De Deus, 1986; Pecora et al, 1991). In India, it was between 2.3% and 0.4% (Neelakantan et al, 2011; Gupta et al, 2015). In Turkey, it ranged from 1.3% to 1.2% (Kartal et al, 1998; Özcan et al, 2012). Interestingly, in contrast to type C canals and additional roots in mandibular molars (Radix Ento and Paramolaris), three-rooted premolars are almost absent in the Asian population. In southern China, according to Walker's study in 1987, no three-rooted premolars were observed. According to Cheng and Weng's study in 2008 and Tian et al.'s study in 2012, three-rooted variations constituted only 1.2% and 0.7%, respectively. In Singapore, according to Loh's study in 1998, no presence of three-rooted premolars were observed. According to the literature review, three-rooted premolars were most frequently found in the populations of Poland (9.2%) and Kosovo (8.1%).

When discussing the morphological variations of three-rooted premolars, there are two types. The first and most commonly encountered type has two buccal roots and one palatal root, while the second type has two palatal roots and one buccal root. This is almost always classified as type 8 according to Vertucci's classification, where each root contains one canal. Three-rooted premolars belong to some of the most demanding and challenging endodontic cases, not only due to their very rare occurrence but also because of difficulties such as accurate diagnosis, access, instrumentation, and prosthetic restoration, which are caused by the delicate root structure.

As previously mentioned, diagnosing three-rooted premolars can be challenging without access to CBCT imaging. However, there are certain radiological features that may indicate the presence of an additional root. For example, if the tooth crown is more flattened in the mesiodistal direction than the buccolingual direction, this could suggest the presence of a buccal or palatal additional root. If the mesiodistal width of the middle or coronal part of the root is the same as or greater than the mesiodistal width of the tooth crown, there is a high likelihood of three-rooted anatomy. A crucial aspect of successful root canal treatment is proper access preparation. For so-called small premolars, a different access approach is recommended compared to the classical oval shape. This access shape resembles a triangle with the base directed buccally and the apex toward the palate, or vice versa if there are two palatal roots.

Regarding instrumentation, it can be more challenging due to potential curvature, and in difficult access cases, there's a risk of instrument separation. Due to the flattening of the mesial and distal buccal roots in the mesiodistal direction, associated with the presence of "danger zones," improper canal instrumentation can lead to complications such as strip perforation. The dangerous zones in the apical part of the buccal and palatal roots of three-rooted premolars were found to be only 0.4 mm and 0.6 mm, respectively. The critical dentin thickness of buccal roots ranged from 0.8 mm in the thinnest area to 1.3 mm, while for palatal roots, it ranged from 1.3 to 2.7 mm.

The critical dentin thickness for canal instrumentation in buccal roots was observed to be 4 mm below the orifice, leading to complete restriction in the use of instruments like Gates-Glidden burs or orifice openers, as their usage significantly increases the risk of perforation. When it comes to instrumentation, caution is advised, particularly for buccal canal preparation, due to their delicate structure and the presence of danger zones. A minimally invasive approach is recommended, involving the use of small or regressed taper instruments. The use of post and core is not recommended.

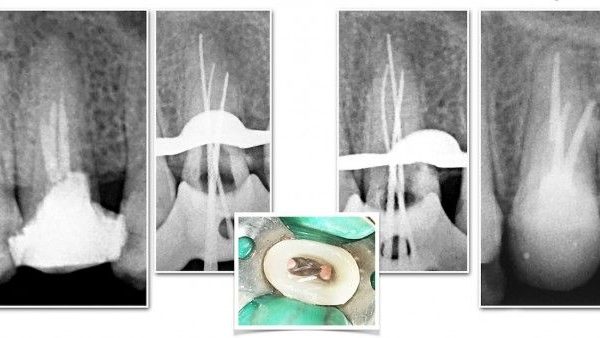

Fig. 1

A female patient, 40 years old with no concomitant diseases, was referred for endodontic treatment of tooth 24; the referring doctor had problems with proper diagnosis of anatomy, finding, and instrumentation of root canals. The referring doctor included an X-ray photo where the outline of the extra root can be seen. Clinical diagnosis: irreversible symptomatic pulpitis tooth 24. On extra-oral examination, no abnormalities, lymph nodes not palpable and not painful, skin coat without changes. On intra-oral examination, tooth 24 with IRM temporary filling on the chewing surface. Percussion,,-,, palpation,,-,, no pockets, no mobility. My attention was also drawn to the not typical structure of the crown of the tooth, which was flattened in the mesiodistal direction, which could also indicate the presence of an additional root.

Fig. 2

CBCT examination 5cmx5cmx5cm cross-section showed the presence of an additional buccal root which may have contributed to the referring dentist's therapeutic difficulties. The peri apical tissues were unchanged, and no perforation or transport of anatomical orifices was found. Interestingly, the adjacent tooth 25 had an atypical C-type anatomy in the buccal root, which is extremely rare. The patient was informed of the clinical situation, possible complications, and prognosis.

Fig. 3

CBCT examination 5cmx5cmx5cm (Carestream 8200) front section showed the presence of an additional buccal root.

Fig. 4

After a previous thorough CBCT analysis, minimally invasive instrumentation of MB and DB canals by crown down to ISO 25.06/30.02 and palatal canal to ISO 30.06 was performed. Performed disinfection of the endodontic space with 5.25% sodium hypochlorite solution and 40% citric acid solution. The liquids were activated with PUI. An intra-oral radiograph was taken in an oblique projection with gutta-percha points. The radiograph confirmed proper canal preparation. Due to minimally invasive access and canal preparation, it was not possible to insert gutta-percha points into all canals at the same time, so two extra radiographs were taken, one with gutta-percha points in the buccal canals and another one in the palatal canal.

Fig. 5

An intra oral radiograph was taken in an oblique projection with gutta-percha point in palatal root canal.

Fig. 6

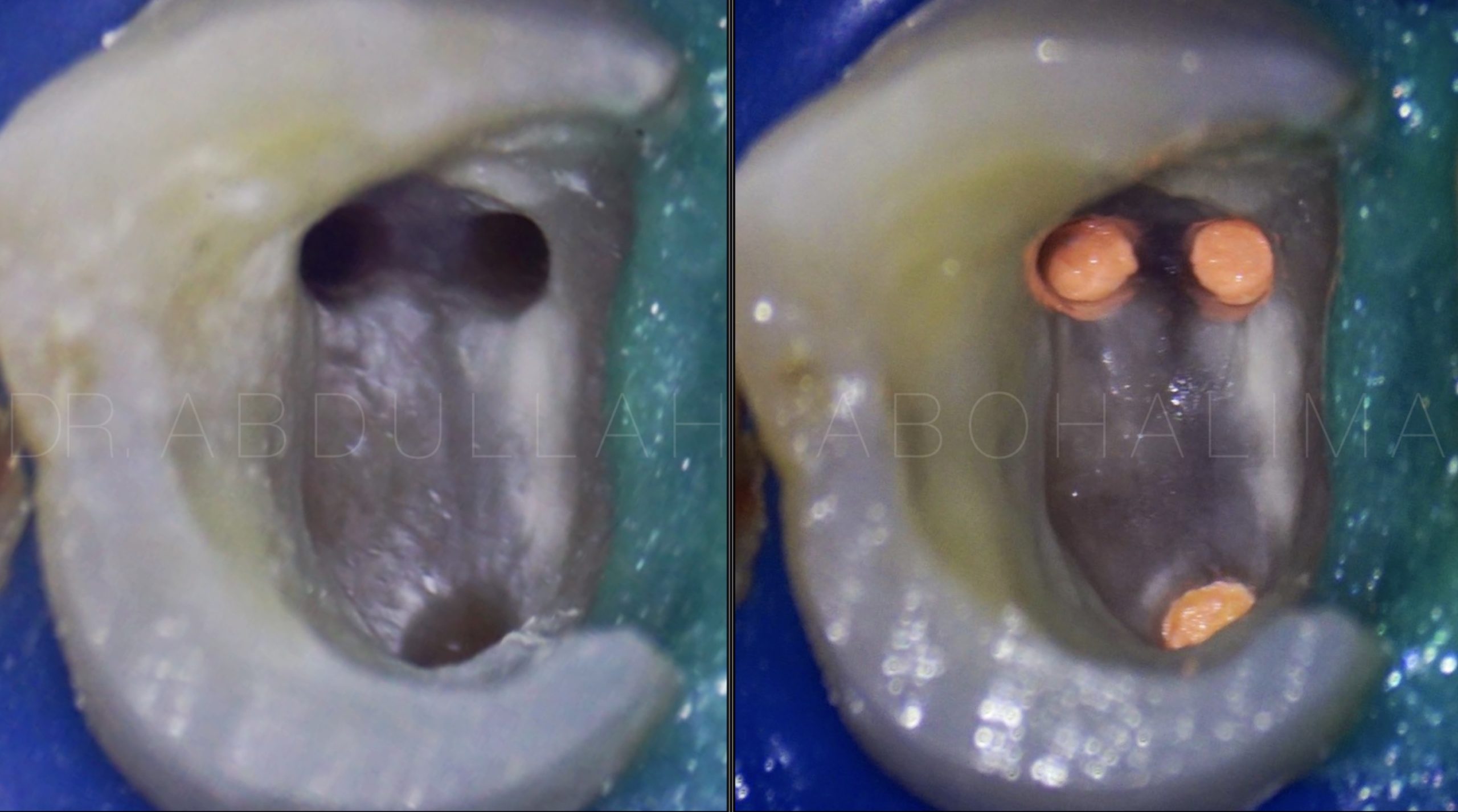

The appearance of the pulp chamber after the phases of shaping and cleaning.

Fig. 7

Obturation was performed using the vertical compaction method using AH+ epoxy sealer and calibrated gutta-percha cones; calibration was performed with a calibration ruler. After obturation, an intra-oral radiograph was taken in oblique projection - the canals were filled correctly.

Fig. 8

About the author:

Mariya Kubatska graduated medical university of Gdansk in 2014. Since graduation highly interested in Endodontics. Member of the European Society of Endodontology, the American Association of Endodontists, member of Polish Endodontic Association, and the Department of Endodontology of the Polish Dental Society. Since 2023 Style Italiano Endodontics fellow. International speaker. Lecturer in Esdent Dental Training Company. Author of case reports in Polish dental magazines. Since 2018 Mariya has worked in Oslo, Norway, focusing on endodontics. In private life piano lover.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the presence of three-rooted premolars, also known as "miniature molars," is a rare anatomical variation that poses challenges for endodontists. The prevalence of this variation varies across different populations and countries, with some regions showing higher occurrences than others. The morphological variations of three-rooted premolars, categorised into two types based on the arrangement of buccal and palatal roots, add to the complexity of their treatment.

Diagnosing three-rooted premolars can be intricate, often requiring advanced imaging techniques such as CBCT to analyse root canal anatomy. Access preparation is a critical step, necessitating a modified approach for these unique cases. Instrumentation becomes particularly challenging due to potential curvatures and delicate root structures, with the risk of complications like strip perforation due to thin dentin areas. Caution must be exercised during instrumentation, especially for buccal canals, to avoid over-instrumentation of danger zones. A conservative and minimally invasive approach is recommended, involving instruments with a small or regressed taper to mitigate risks.

In the realm of endodontic treatment, addressing three-rooted premolars demands precision, skill, and a comprehensive understanding of their intricate anatomy.

Bibliography

Root and Root Canal Morphology of Maxillary First Premolars: A Literature Review and Clinical Considerations. Ibrahim Ali Ahmad, BDS, MSc, JBE,* and Mohammad Ahmad Alenezi, BDS, MFDRCSI, MScD.

An Ex Vivo Study of Root Canal System Configuration and Morphology of 115 Maxillary First Premolars. Thomas Gerhard Wolf, DDS,*† Christoph Kozaczek, DDS,* Mark SiegristLT,‡

Madlena Betthasuser, DDS,x Frank Paque, DDS,k and Benjamín Brisen~o-Marroquín, DDS, MDS, Dr med dent*†

Clinically Relevant Dimensions of 3-rooted Maxillary Premolars Obtained Via High-resolution Computed Tomograph. Rafael Chies Hartmann, DDS,* Flavia E.R. Baldasso, DDS,* Carolina P. Stu€rmer, DDS,* Monique Dossena Acauan, DDS,* Roberta Kochenborger Scarparo, DDS, MS, PhD,* Renata Dornelles Morgental, DDS, MS, PhD,* Susan Bryant, MS,†

Paul M. Dummer, DDS, MS, PhD,† Jose Antonio Poli de Figueiredo, DDS, MS, PhD,* and Fabiana Vieira Vier-Pelisser, DDS, MS, PhD*

An Ex Vivo Study of Root Canal System Configuration and Morphology of 115 Maxillary First Premolars.Thomas Gerhard Wolf, DDS,*† Christoph Kozaczek, DDS,* Mark Siegrist, LT,‡Madlena Bettha€user, DDS,x Frank Paque, DDS,k and Benjamín Brisen~o-Marroquín, DDS, MDS, Dr med dent*†

Identification and endodontic management of three canaled maxillary premolars. Steven M.Sieraski, DDS, MS,Gary.N Taylor, DDS, MS, and Richard A.Kohn, DDS, MS