Endodontically treated tooth dyschromia: causes and solutions

10/06/2023

Fellow

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

The discoloration of a dental element can create a strong aesthetic discomfort and can often be the first clinical sign of an ongoing pulp disease. The causes of dyschromias are many and, as always, a correct diagnosis is the cornerstone of solving the problem.

The causes that can lead to a chromatic variation of a tooth can be divided into extrinsic and intrinsic: the extrinsic ones, by definition, are produced by the application of chromophore substances or bacteria on the tooth surface. The resolution of this type of pigmentation, after a careful analysis of the dental / medical history and a correct diagnosis, is therefore relatively simple. Their treatment is usually limited to professional hygiene, home hygiene instruction including the use of toothpastes containing chelating agents (sodium citrate, citric acid, or proteolytic enzymes), and food or drink chromophores restriction.

The intrinsic ones, on the other hand, originate from the integration of chromogenic substances within the dentin structure or enamel. We can classify them into two categories: preeruptive and posteruptive.

The most frequent causes of intrinsic preeruptive dyschromia are represented by the ingestion of fluoride or the administration of tetracyclines during the period of odontogenesis; however, cases of congenital enamel/dentine defects or hematological disorders are less frequent.

On the other hand, postoperative intrinsic dyschromias can in turn be classified as traumatic and atraumatic.

In fact, following a facial trauma, the dental microcirculation can be compromised and damaged, causing a small internal hemorrhage: the blood therefore has the opportunity to propagate inside the dentinal tubules and undergo a process of hemolysis, releasing hemoglobin. The latter is gradually degraded creating ferrous deposits which, when combined with the hydrogen sulphate, transforms into ferrous sulphate, with a black/bluish appearance.

In the case of necrosis with non-traumatic etiology, the grayish-brown coloration is given by the protein degradation of the pulp tissue.

Even endodontic therapy itself can cause discoloration of the dental element: incorrect access to the chamber or insufficient three-dimensional filling of the endodontic plexus can leave remains of pulp in the untreated portion which, degrading, can dye the tooth.

Even post-endodontic chamber restorations can cause color variations:

silver amalgam, if used to reconstruct the ETTs, by releasing metal ions, can dye the surrounding dentin of a gray tending to black color which is extremely difficult to correct with chemical treatment6.

Composite restorations, if poorly adapted, can allow chromophore substances or bacteria to filter through micro-cracks, which in turn can color the dentin.

The correction of dyschromias of endodontic origin (intrinsic postoperative) can be corrected both prosthetically and chemically.

The prosthetic correction of chromatic defects of this type involves the preparation of the dental element and its covering with materials that do not allow an excessive passage of light (ceramic metal, zirconia). This type of solution, especially in young subjects resulting from dental trauma, is often unnecessarily invasive and the chemical approach therefore finds its best indication.

Chemical bleaching, or walking bleach, is a technique that involves the intracoronal application of hydrogen peroxide, whether it is direct, by applying it directly into the endodontic cavity, or indirectly, through a chemical reaction of carbamide peroxide or di sodium. Peroxides , through an oxidative process, degrade the compounds responsible for discoloration.

The modern gold standard, which involves the use of sodium perborate mixed with distilled water in a ratio of 2:1 (g/ml), was described for the first time by Marsh: it currently represents the most widespread and recommended intracoronal clearing method in textbooks.

The correct application requires a careful assessment of the root filling beforehand: the failed coronal seal or the failed three-dimensional seal can lead to the filtration of the whitening agent along the root dentin leading to sometimes irreparable damage.

Once the correct endodontic seal has been established, the obturation material is removed up to 2mm below the CEJ. This space will then be filled with a "barrier" material that prevents the filtration of the bleaching agent through the underlying filling material. The latter will be positioned up to 1 mm coronal with respect to the corresponding external probing of the attachment and this operation can be easily completed thanks to the use of a periodontal probe. As a protective filling material we can use temporary materials such as IRM or Cavit, which will then be removed, or definitive materials such as glass ionomer cements.

All these maneuvers must be carried out under careful isolation with a rubber dam in order to prevent contact of the bleach with the surrounding tissues (peroxides are caustic at high concentrations) and to preserve the coronal endodontic seal.

The cavity is then cleaned using ethyl alcohol which dehydrates the dentin, reducing the surface tension and thus improving the penetration of the bleach through the dentinal tubules. Some authors have proposed the use of 37% orthophosphoric acid for the purpose of a greater opening of the dentin tubules, but recent studies state that its use has not proved to be clinically relevant in improving the whitening action.

The application of sodium perborate can be conveyed by an amalgam holder and the cavity will be sealed, after etching the enamel, with a composite material, in order to prevent the leakage of the material into the oral cavity and to prevent further filtration inside of it.

The whitener will be replaced every 3-7 days until the desired color is achieved.

It should be remembered that, especially in large cavities, the color of the definitive filling material may influence the chromatic outcome: if we have not achieved the desired color, we can fill the cavity with a very light composite to compensate for the discolouration.

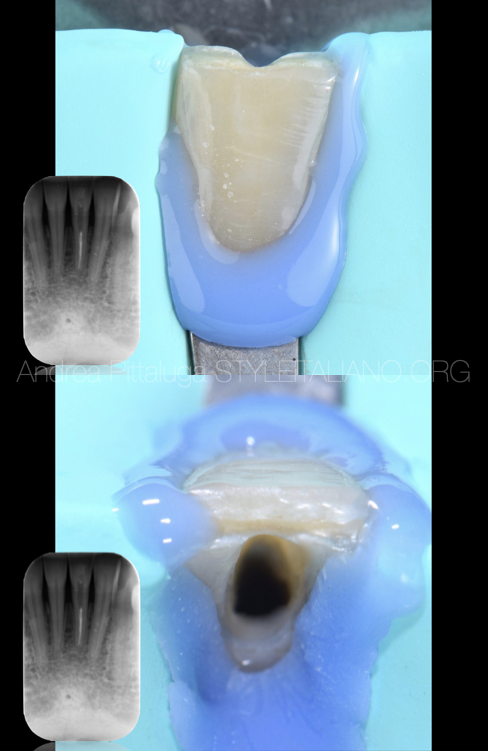

Fig. 1

A colleague was not satisfied with the color of the lower left central incisor: the tooth had been treated endodontically years earlier following a trauma and the previous root canal therapy, although it had never given relapses, shows an inadequate three-dimensional seal .

Fig. 2

After isolation with a rubber dam, we then proceed to orthograde retreatment thanks to the use of mechanical and reciprocating instrumentation. The apex, slightly reworked, was shaped with a 30/06 tool.

Fig. 3

The obturation technique used was the Warm Vertical Condensation, paying attention during the back filling to leave the necessary space for the protective material.

Fig. 4

One week after retreatment, approximately 2 mm of light-curing glass ionomer cement (Vitrebond - ESPE 3M) is applied and sodium perborate and distilled water are applied. The procedure was repeated twice until the desired clinical and aesthetic result was obtained, then the most superficial portion of glass ionomer was removed and the endodontic cavity was permanently sealed using the adhesive technique. The final photo represents the 60-day follow up.

Conclusions

The correct application of the protocols and the use of less aggressive whitening substances (sodium perborate), although the non-aesthetic perfect result cannot always be achieved, leads to more than satisfactory clinical results, exponentially reducing the burden of complications.

Bibliography

1.Perceptions of Dental Dyschromia by Patients and Dentist

Delia Cristina Greta et al. Int J Prosthodont. 2021 March/April.

. 2021 March/April;34(2):154–162.

doi: 10.11607/ijp.6312. Epub 2020 Jun 26.

2.The bleaching of teeth: a review of the literature

Andrew Joiner. J Dent. 2006 Aug.

. 2006 Aug;34(7):412-9.

doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2006.02.002. Epub 2006 Mar 29.

3.Crown discoloration of endodontically treated teeth: Causes, treatment and complications G. Sotiropoulos, E.-T. Farmakis, K. Naiske, M. Antoniadou

Hellenic Stomatological Review 57: 219-250, 2013 paper received 15/5/2014 - accepted 21/7/2014

4.Present status and future directions - Managing discoloured teeth

Bill Kahler. Int Endod J. 2022 Oct.

Free PMC article

. 2022 Oct;55 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):922-950.

doi: 10.1111/iej.13711. Epub 2022 Mar 8.

5.Nonvital tooth bleaching: a review of the literature and clinical procedures

Gianluca Plotino et al. J Endod. 2008 Apr.

. 2008 Apr;34(4):394-407.

doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.12.020. Epub 2008 Feb 15.

6.Grey discolouration and marginal fracture for the diagnosis of secondary caries in molars with occlusal amalgam restorations: an in vitro study

M P Rudolphy et al. Caries Res. 1995.

. 1995;29(5):371-6.

doi: 10.1159/000262095.

7.Bleaching of nonvital teeth. A clinically relevant literature review

Brigitte Zimmerli et al. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2010.

Free article

. 2010;120(4):306-20.

8.Review of the current status of tooth whitening with the walking bleach technique

T Attin et al. Int Endod J. 2003 May.

. 2003 May;36(5):313-29.

doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00667.x.

9.The "walking" bleach technique

H Putter et al. J Esthet Dent. 1989 Nov-Dec.

. 1989 Nov-Dec;1(6):191-3.

doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.1989.tb00501.x.

10.In vitro comparison of different types of sodium perborate used for intracoronal bleaching of discoloured teeth

H Ari et al. Int Endod J. 2002 May.

. 2002 May;35(5):433-6.

doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00497.x.

11.Effect of smear layer removal on bleaching of human teeth in vitro

D J Horn et al. J Endod. 1998 Dec.

. 1998 Dec;24(12):791-5.

doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(98)80003-4.

12.Speed bleaching: the importance of temporary filling with hermetic sealing

Alessandro Traviglia et al. Int J Esthet Dent. 2019.

. 2019;14(3):310-323.