Antique Silver replaced by conventional Gutta percha: A Retreatment Revival

03/06/2025

Viresh Chopra

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

This clinical case presents the nonsurgical endodontic retreatment of a mandibular first molar initially obturated with silver points. The tooth exhibited persistent periapical pathology and contained a missed, partially calcified canal, contributing to endodontic failure. The retreatment strategy involved the careful retrieval of silver points followed by meticulous canal negotiation and shaping using a modern rotary file system. Advanced magnification and irrigation protocols facilitated the identification and management of the calcified canal. The case was completed with warm vertical compaction of gutta-percha and obturation using a bioceramic sealer, achieving a homogenous and well-adapted fill. Postoperative radiographs confirmed the successful management of the previously missed anatomy and resolution of periapical pathology. This case underscores the significance of employing contemporary rotary retreatment systems and three-dimensional obturation techniques in salvaging teeth previously treated with outdated materials such as silver points.

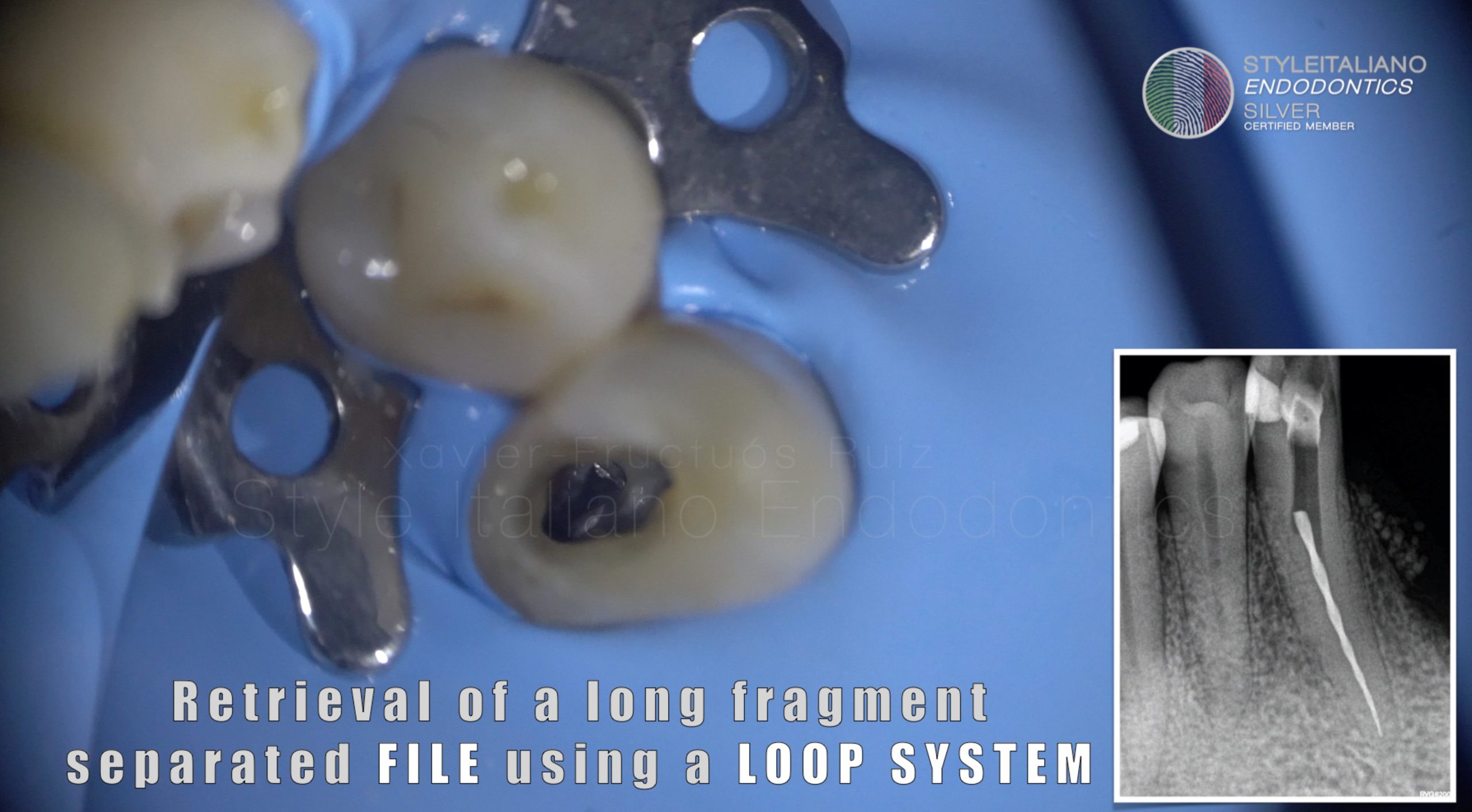

Fig. 1

Case History

A 42-year-old female presented with a chief complaint of tenderness on biting in the lower right posterior region. The patient reported a history of root canal treatment on the same tooth—mandibular left first molar (tooth 36)—performed approximately 17 years ago. The tooth had since been part of a fixed dental prosthesis (bridge), which the patient noted had deteriorated over time.

Clinical examination revealed a faulty bridge on teeth 48-46. Tooth 48 has tenderness to percussion on tooth 48, with no signs of swelling or sinus tract. Radiographic evaluation showed a previously treated tooth with silver point obturation in both mesial canals (Fig 1). The obturation appeared inadequate in terms of length and adaptation. Additionally, a periapical radiolucency was observed, suggestive of chronic periapical pathology. The bridge restoration exhibited poor marginal adaptation and likely contributed to coronal leakage.

Based on the clinical and radiographic findings, a diagnosis of previously treated tooth with symptomatic apical periodontitis was made. Nonsurgical endodontic retreatment was indicated to eliminate persistent infection, manage the periapical pathology, and preserve the tooth.

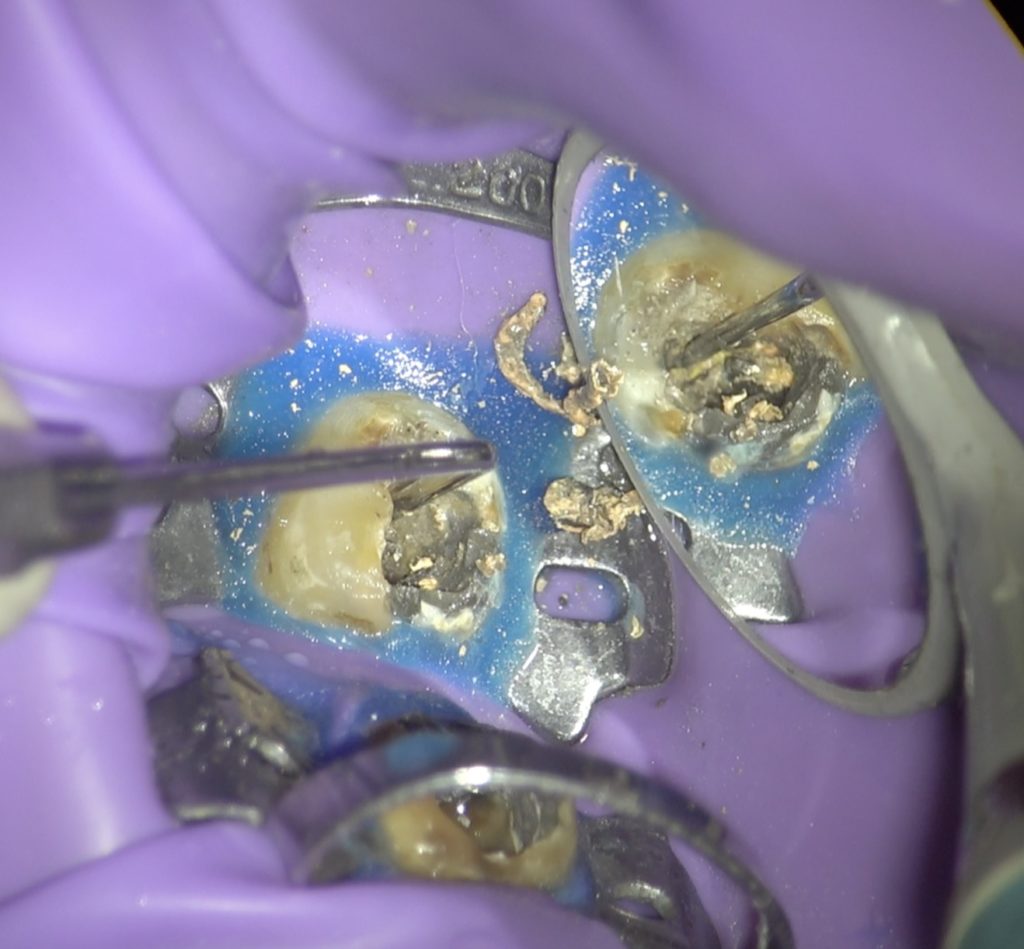

Fig. 2

Step wise Treatment provided

- Removal of Existing Prosthesis

- The failing fixed dental prosthesis (bridge) was carefully sectioned and removed to provide unobstructed access to the underlying tooth (tooth 48).

- Re-accessing the Pulp Chamber

-

- Under rubber dam isolation and high magnification using a dental operating microscope (DOM), the existing access cavity was refined to expose the pulp chamber of tooth 48. (Fig 2)

- Residual temporary filling and debris were removed to gain a clear view of the canal orifices.

- Identification of Previous Filling Material

-

- Silver points were identified in both mesial and distal canals. Their presence was confirmed visually under the DOM and radiographically.

- Removal of Silver Points

-

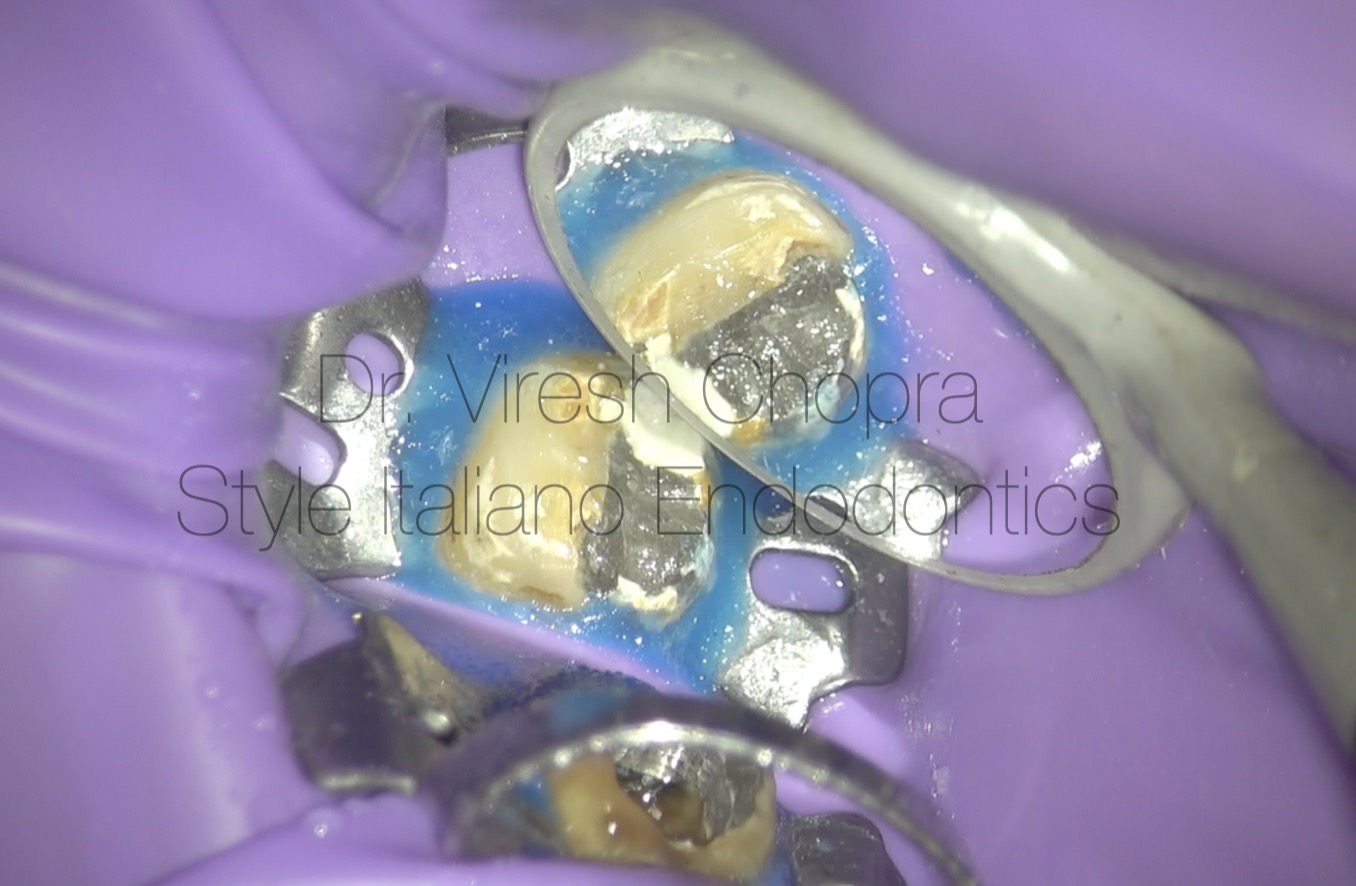

- The silver points were carefully exposed, dislodge them from surrounding cement with endodontic explorer and remove them with tweeze, preserving canal anatomy. (Fig 3) (video 1)

- Canal patency was verified with small hand files.

- Canal Negotiation and Shaping

-

- Glide path preparation was performed following canal negotiation.

- Cleaning and shaping were accomplished using a rotary file system under continuous irrigation with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite.

- A final rinse with 17% EDTA was used to remove the smear layer and prepare the dentin for sealer penetration.

Fig. 3

Step wise Treatment provided

Disinfection Protocol

- Final irrigation protocol included activation of irrigants (NaOCl and EDTA) to enhance disinfection.

- No intracanal medicament was deemed necessary as the retreatment was completed in a single session.

Obturation

- After drying the canals with sterile paper points, obturation was carried out using warm vertical condensation of gutta-percha along with a bioceramic sealer to ensure a dense, three-dimensional seal.

- Radiographs confirmed proper length, fill density, and adaptation of the obturation in all canals.

Coronal Seal and Restoration Plan

- A bonded composite resin core was placed to seal the access cavity.

- The patient was advised to have a new full-coverage restoration placed to ensure long-term protection of tooth 48.

Root canal re-treatment protocol followed:

The removal of the silver points began with careful inspection under a dental operating microscope. A DG16 endodontic explorer was employed to tactically engage the coronal portion of the silver points. By applying gentle apical-lateral pressure, the explorer was used to disrupt any cementitious or dentinal attachments securing the silver cones within the canal walls. This delicate manipulation helped to mobilize the silver points without causing undue stress or damage to the surrounding dentin.

Once sufficient loosening was achieved and the points exhibited visible mobility, fine-tipped tweezers were introduced into the access cavity. Under continuous magnification, the silver points were securely grasped and slowly withdrawn from the canals in a controlled manner. (Video 1)The procedure was performed with precision to avoid root fracture or separation of the metal within the canal. Successful retrieval of the silver points allowed for unobstructed canal negotiation and subsequent disinfection.

Following the retrieval of the silver points, residual gutta-percha material within the canals was removed using a dedicated rotary retreatment file system. (Video 2) The procedure was carried out entirely under high magnification using a dental operating microscope, which provided enhanced visualization of the canal anatomy and ensured precision during instrumentation.

The retreatment files were employed in a crown-down approach, progressively removing the gutta-percha while simultaneously enlarging the canals. Throughout the procedure, profuse irrigation with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite was used to aid in the flushing of debris, dissolve organic remnants, and enhance canal cleanliness. Irrigant activation techniques were also employed intermittently to improve the effectiveness of debridement, especially in complex or curved regions of the canal system. The combined use of rotary retreatment instrumentation and microscopic guidance allowed for thorough and conservative removal of obturation materials, ensuring the canals were fully prepared for subsequent shaping and disinfection.

After the canals were cleaned, shaped, and dried, a master cone (MC) trial was done to check the fit of the gutta-percha cones. Each cone was placed into the canal up to the working length to ensure it fit snugly, especially at the tip (apex). The fit was checked visually and with an X-ray.

Once the fit was confirmed, the canals were filled (obturated) using gutta-percha and a bioceramic sealer. (Video 3)The sealer was applied inside the canals to help seal any small spaces. The gutta-percha was then placed into the canals and gently packed to ensure a good seal. The clinical picture and the final X-ray showed a proper, tight fill of all canals. (Fig 4 and Fig 5)

Confluencing canals in this case:

During the sealer placement phase, it was observed under magnification that the two mesial canals exhibited confluence—meaning they joined together into a single canal pathway before reaching the apex. This anatomical variation, known as canal confluence, is a common feature in mandibular molars and holds important clinical implications.

In this case, the confluence was clearly visible as the bioceramic sealer flowed smoothly from one canal into the other, (video 4) confirming their anatomical connection. Recognizing this confluence is critical during obturation, as it helps ensure that both canals are adequately filled and sealed, reducing the risk of voids or unfilled spaces at the point of merging.

Proper management of confluencing canals ensures that the entire apical third is sealed as a single unit, which is essential for preventing reinfection. It also reinforces the importance of thorough cleaning and shaping of both canals up to their merging point, as any debris or bacteria left behind in the confluence area can compromise long-term success.

In this case, the visible flow of sealer between the mesial canals provided direct confirmation of their communication and ensured that a dense, three-dimensional obturation was achieved.

Fig. 4

Obturated canals

Fig. 5

Radiographic verification of the obturation

Conclusions

This case highlights the successful nonsurgical retreatment of a mandibular third molar (tooth 48) previously obturated with silver points nearly two decades ago. The patient presented with symptoms of tenderness on biting and radiographic evidence of periapical pathology, indicating failure of the initial treatment. Outdated obturation techniques, such as the use of silver points, are associated with significant limitations including poor adaptation to canal walls, corrosion, and difficulty in achieving a hermetic seal—factors that contribute to long-term endodontic failure.

The retreatment approach employed in this case underscores the importance of modern endodontic principles and tools in managing previously treated teeth. The use of a dental operating microscope facilitated the identification and retrieval of silver points and the detection of complex anatomy, including a missed and confluencing mesial canal system. The careful removal of the existing filling materials, thorough chemomechanical debridement, and the adoption of a bioceramic sealer with warm gutta-percha obturation ensured complete three-dimensional sealing of the root canal system.

Particularly significant was the recognition of canal confluence in the mesial root, which was confirmed during sealer placement under magnification. Proper understanding and management of such anatomical complexities are vital in retreatment cases to prevent reinfection and promote periapical healing.

This case reaffirms the value of incorporating advanced magnification, rotary retreatment systems, and bioceramic materials into contemporary endodontic practice. With meticulous technique and adherence to evidence-based protocols, even teeth with a poor initial prognosis—such as those treated with outdated materials like silver points—can be predictably salvaged, contributing to tooth longevity and patient satisfaction.

Bibliography

- Schilder H. Filling root canals in three dimensions. Dent Clin North Am. 1967;11(2):723–744.

- Ingle JI, Beveridge EE. The removal and reuse of silver points. J Am Dent Assoc. 1957;55(6):721–726.

- Stabholz A, Friedman S. Endodontic retreatment—Case selection and technique. Part 2: Treatment planning for retreatment. J Endod. 1988;14(12):607–614.

- Camilleri J. Bioceramics in endodontics. Int Endod J. 2014;47(7):581–598.

- Zhou HM, Shen Y, Zheng W, Li L, Zheng YF, Haapasalo M. Physical properties of 5 root canal sealers. J Endod. 2013;39(10):1281–1286.

- Plotino G, Grande NM, Isufi A, Ioppolo P, Pedullà E, Bedini R, et al. Fracture strength of endodontically treated teeth with different access cavity designs. J Endod. 2017;43(6):995–1000.