A recipe for disaster: no pre-op x-ray and wrong access cavity

25/02/2021

Francesca Cerutti

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /var/www/vhosts/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/endodontics.styleitaliano.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /var/www/vhosts/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/endodontics.styleitaliano.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Endodontic success often depends on canal debridement, disinfection, and canal obturation. Access to the canal is one key to debridement, in fact an appropriately designed access cavity assures unobstructed straight-line access to the apical third of the root canal.

The endodontic treatment of maxillary incisors, especially the lateral incisors, was reported as the last successful by several authors.

Knowledge of the root canal anatomy and its variations is a prerequisite for successful endodontic treatment, above all in situations in which the anatomy of the pulp chamber has been altered, i.e. in case of calcification of the pulp.

Procedural accidents are eventualities that may occur during endodontic treatment because of lack of attention to detail or even unforeseeable situations.

Teeth subjected to traumas are more likely to develop calcifications; clinical studies have reported 20%–71% success in locating posttraumatically obliterated canals. The use of cone-beam computed tomographic (CBCT) imaging enables more accurate treatment planning; however, the conventional access opening approach to locate the canals may lead to aggressive loss of sound dentin and increased risk of iatrogenic errors, thereby reducing the long-term prognosis.

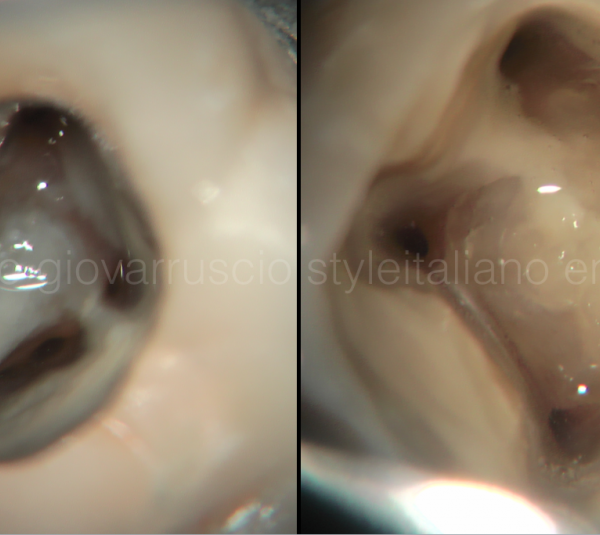

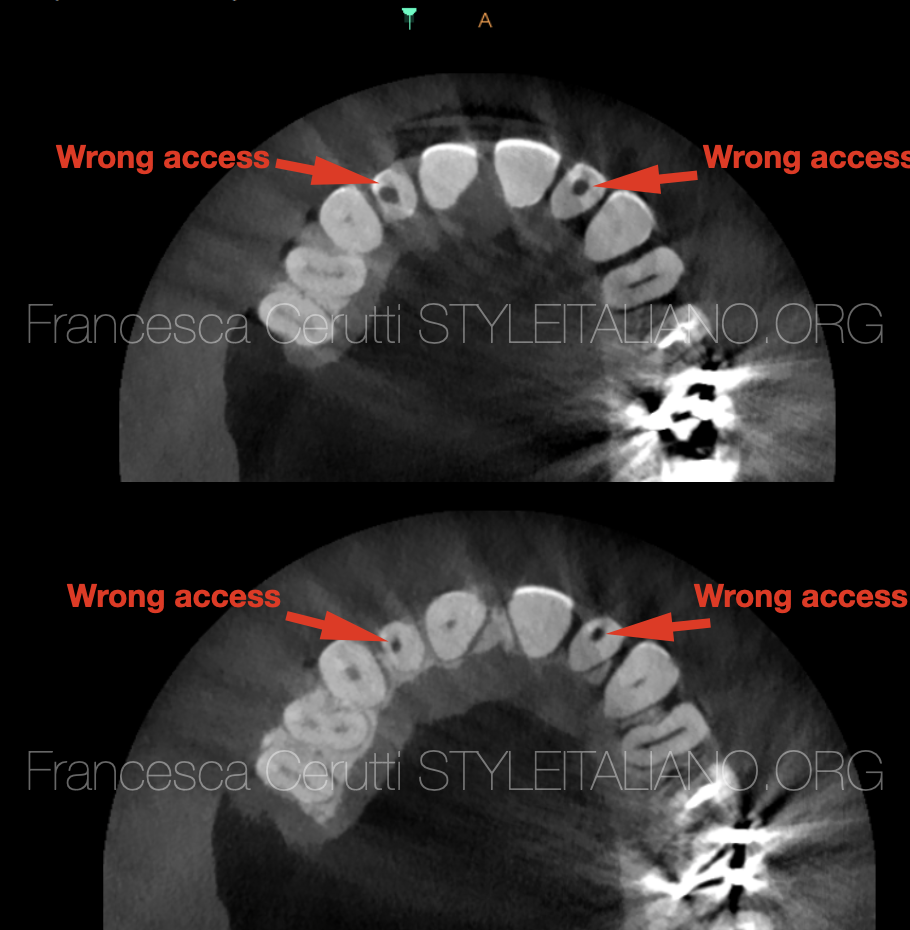

Fig. 1

This patient was referred to me by a colleague who tried to do the root canal treatment on the two maxillary lateral incisors.

He took a panoramic x-ray and started doing the access cavity. When he realized he could not find the root canal, he stopped the procedure and sent me the patient.

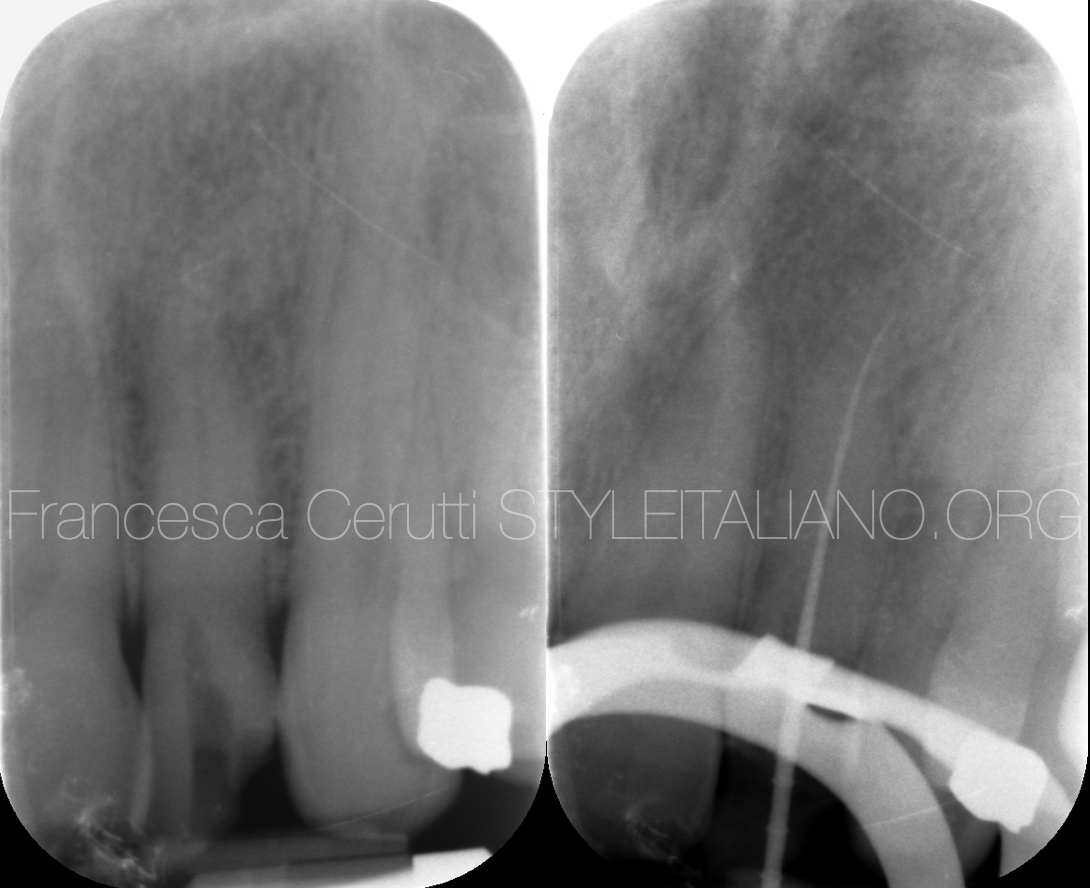

I took two periapical x-rays in order to assess the anatomy of the tooth and the extent of the damage.

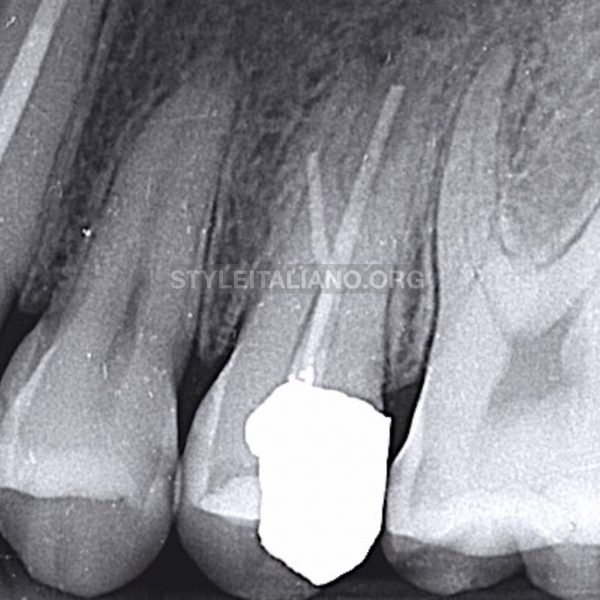

Fig. 2

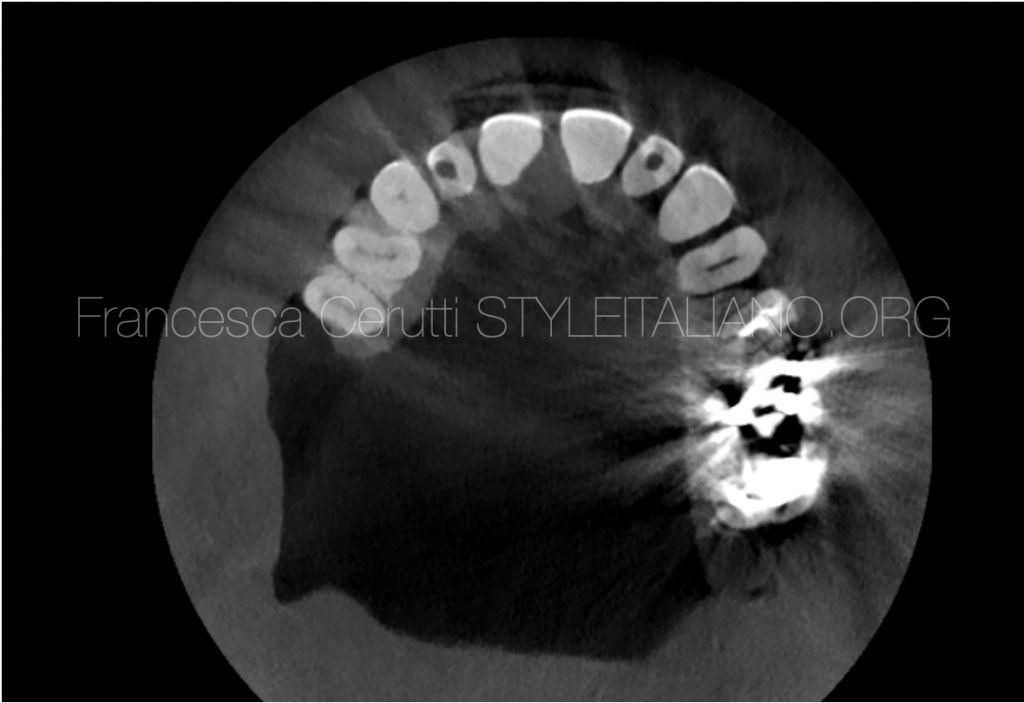

I also took a CBCT in order to assess that there were no perforations or stripping and to locate the position of the root canals.

The slices on the right show the position of the wrong access performed by the colleague.

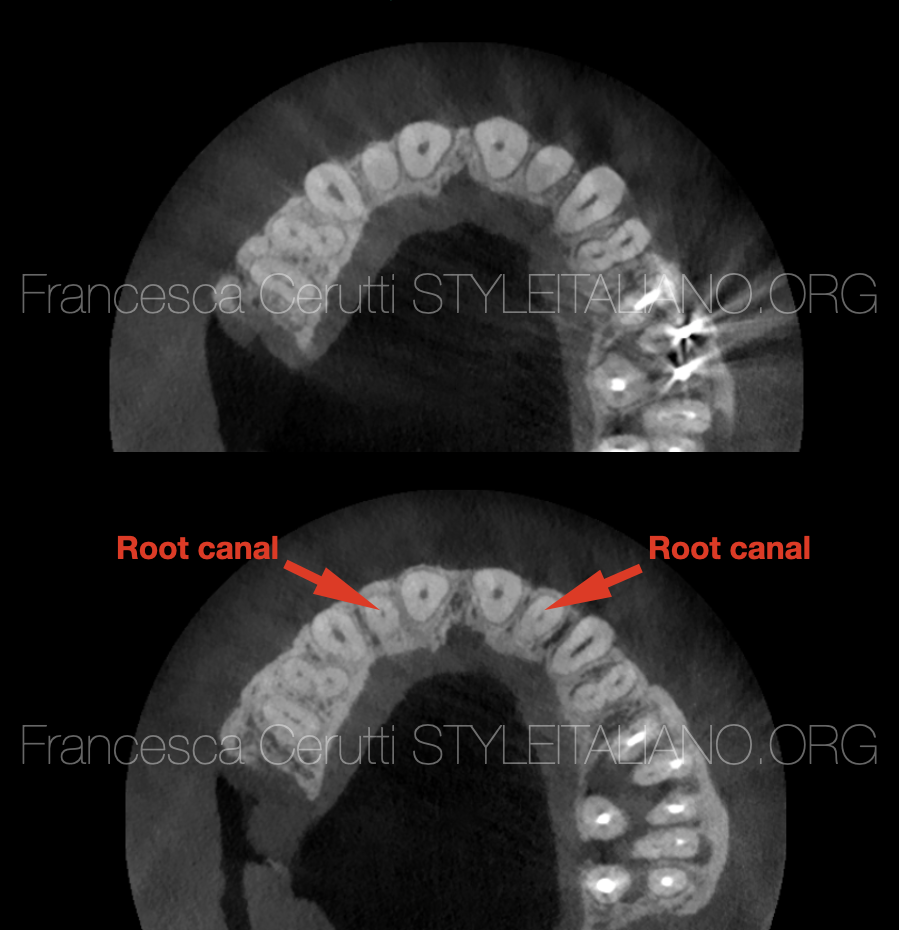

Fig. 3

The first slice shows the presence of calcified tissue in both teeth above the root canal. The second slice shows the position of the canals, in the centre of the root as expected.

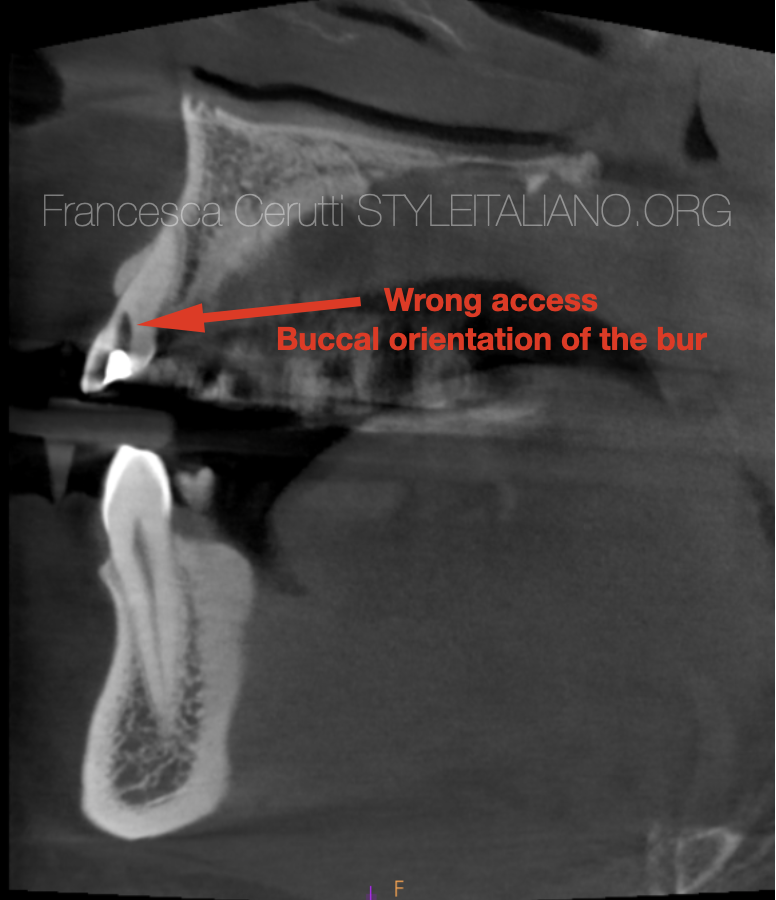

Fig. 4

The tooth 2.2 presented an access done with an excessively buccal orientation of the bur, but luckily the colleague stopped before doing a perforation.

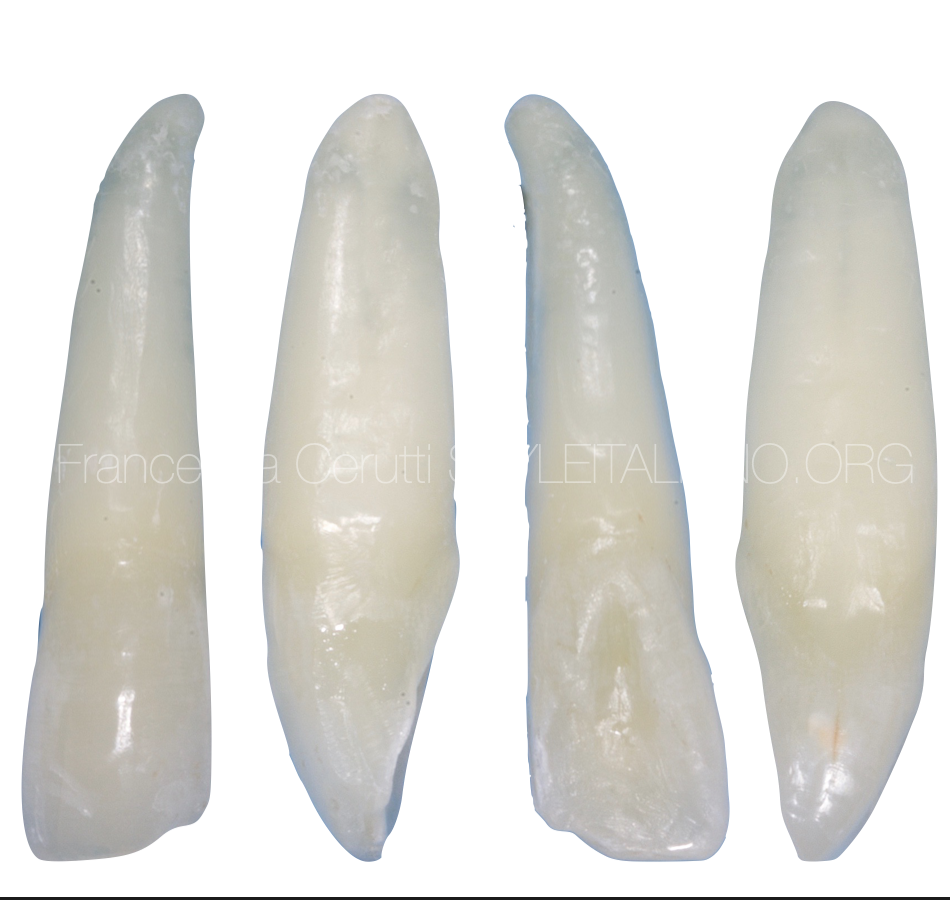

Fig. 5

In anterior teeth straight-line access is achieved through a cavity, made on incisal edge or even labial surface of the tooth. Location of access cavity in anterior teeth determines the amount of preserved dentin in the cingulum area, which is important for the ferrule effect.

Fig. 6

It is always important to keep in mind the orientation of the buccal surface of the tooth, in order to correctly position the bur we are using for the access cavity.

Fig. 7

I performed a multiple isolation, then placed a clamp on the tooth 2.2.

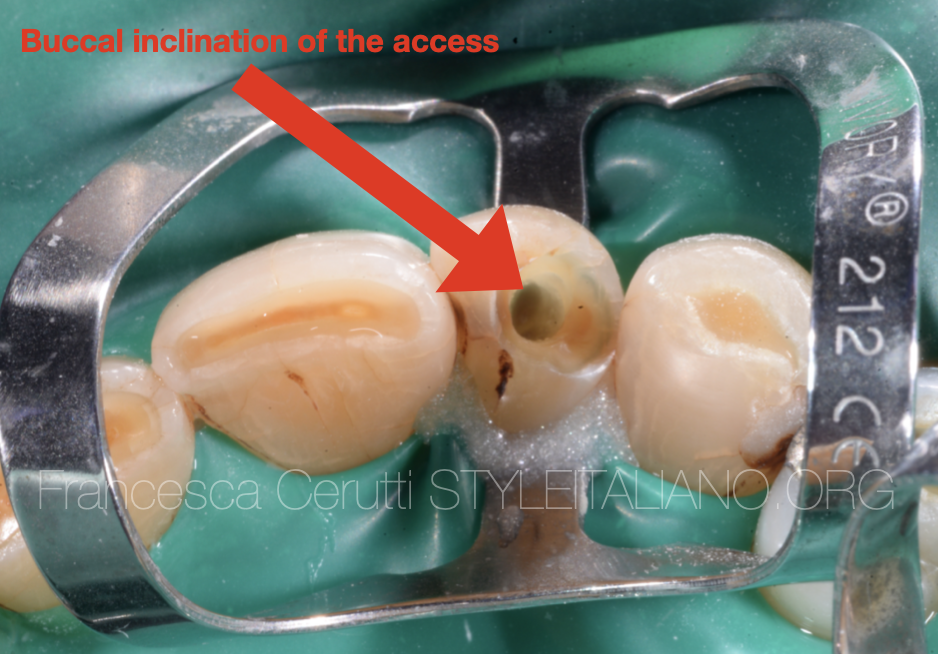

This is the appearance of the access cavity performed by the referring dentist.

Fig. 8

As the arrow shows, the path taken by the bur was too buccal

Fig. 9

Keeping in mind the anatomy of the tooth and looking at the CBCT, I corrected the access with burs and US tips.

Fig. 10

Then I started scouting the root canal with a 10.04 rotary Ni-Ti file.

The file easily penetrated the first millimeters of the root canal. At this point, I scouted the root canal whit a 0.8 SS file, always attached to the apex locator. I proceeded with watch winding movements and used a chelator in order to make the file proceeding easier.

I took an intra-operative x-ray to verify the correct position of the file into the root canal.

Fig. 11

Once I was able to scout the root canal to the apex with a .10 SS file, I used Ni-Ti heat treated rotary files in order to shape the root canal.

Then, I cleaned it thoroughly with sodium Hypochlorite carried by a polypropylene cannula that I was able to bring to the working length.

The irrigant was activated with an ultrasonic file after each cycle.

Fig. 12

The picture shows the tooth after cleaning and shaping

Fig. 13

I filled the tooth with warm gutta-percha using the carrier-based technique, then I restored it with composite.

Fig. 14

In the following appointment I took care of the right lateral incisor.

Fig. 15

I isolated the tooth which, in this case, showed an access cavity that was too lateral and too buccal.

By looking at the CBCT I moved more mesially and I was able to locate the root canal opening. I used a bur followed by US tips.

Fig. 16

I used the same approach as before and I was able to reach the WL with a .10 file.

Fig. 17

This is the tooth after cleaning and shaping.

Fig. 18

Pre and post-op x-ray.

The tooth was filled with warm gutta percha, then restored with composite.

Fig. 19

The patient was sent back to the referring dentist to go on with their treatment plan, which involved placing crowns on the six front teeth and implants on the missing teeth.

Fig. 20

Occlusal view.

Conclusions

Knowing the anatomy and carefully analyzing the pre operative records is extremely important to avoid iatrogenic damages.

In case of alterations of the original anatomy of the tooth, the use of magnifications, an adequate light source and a CBCT can help in solving the case.

Bibliography

Zillick RM, Jerome JK, Arbor A. Endodontic access to maxillary lateral incisors. Oral Surg. 1981;52(4):443-5.

Krapez J, Fidler A. Location and dimensions of access cavity in permanent incisors, canines, and premolars. Journal of conservative dentistry : JCD. 2013;16(5):404-7.

Tang L, Sun TQ, Gao XJ, Zhou XD, Huang DM. Tooth anatomy risk factors influencing root canal working length accessibility. International journal of oral science. 2011;3(3):135-40.

Casadei BA, Lara-Mendes STO, Barbosa CFM, Araújo CV, de Freitas CA, Machado VC, et al. Access to original canal trajectory after deviation and perforation with guided endodontic assistance. Australian endodontic journal : the journal of the Australian Society of Endodontology Inc. 2020;46(1):101-6.

Torres A, Shaheen E, Lambrechts P, Politis C, Jacobs R. Microguided Endodontics: a case report of a maxillary lateral incisor with pulp canal obliteration and apical periodontitis. Int Endod J. 2019;52(4):540-9.