Geriatric endodontics: case report and clinical considerations

21/10/2023

Fellow

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

The increased life expectancy has led to the increase in numbers of elderly patients seeking dental treatments, and more precisely root canal treatments. According to a survey of diplomates of the American Board of Endodontics, patients over 65 years of age represent 26% of all endodontically treated patients. (1) Maintaining natural and functional teeth plays a role in the quality of life because it is directly related to the quality of food intake, digestion and overall health (2). Endodontic treatment is a key step to maintaining and saving teeth.

It is important to know that the pulpo-dentinal complex ages over time, due to physiological and pathological causes (3,2):

- Secondary dentine deposits throughout life, from the time the tooth has completed root formation and is in occlusion.

- Tertiary dentine deposits in response to insult to the pulp: caries, trauma, attrition, bruxism…

- Occlusion of dentinal tubules happens by deposition of peritubular dentine.

- Dentine in older patients has less water content, making it more susceptible to cracks.

- Pulpal neurons degenerate, starting from the pulp horns and moving apically.

- Diminishment in pulp vascularity.

- Increase in pulp fibrosis.

Fig. 1

A 75 year old male patient presented to the clinic with a chief complaint of food impaction around his lower left first molar. He did not complain of pain upon mastication or thermal stimulus, and did not report any history of previous pain.

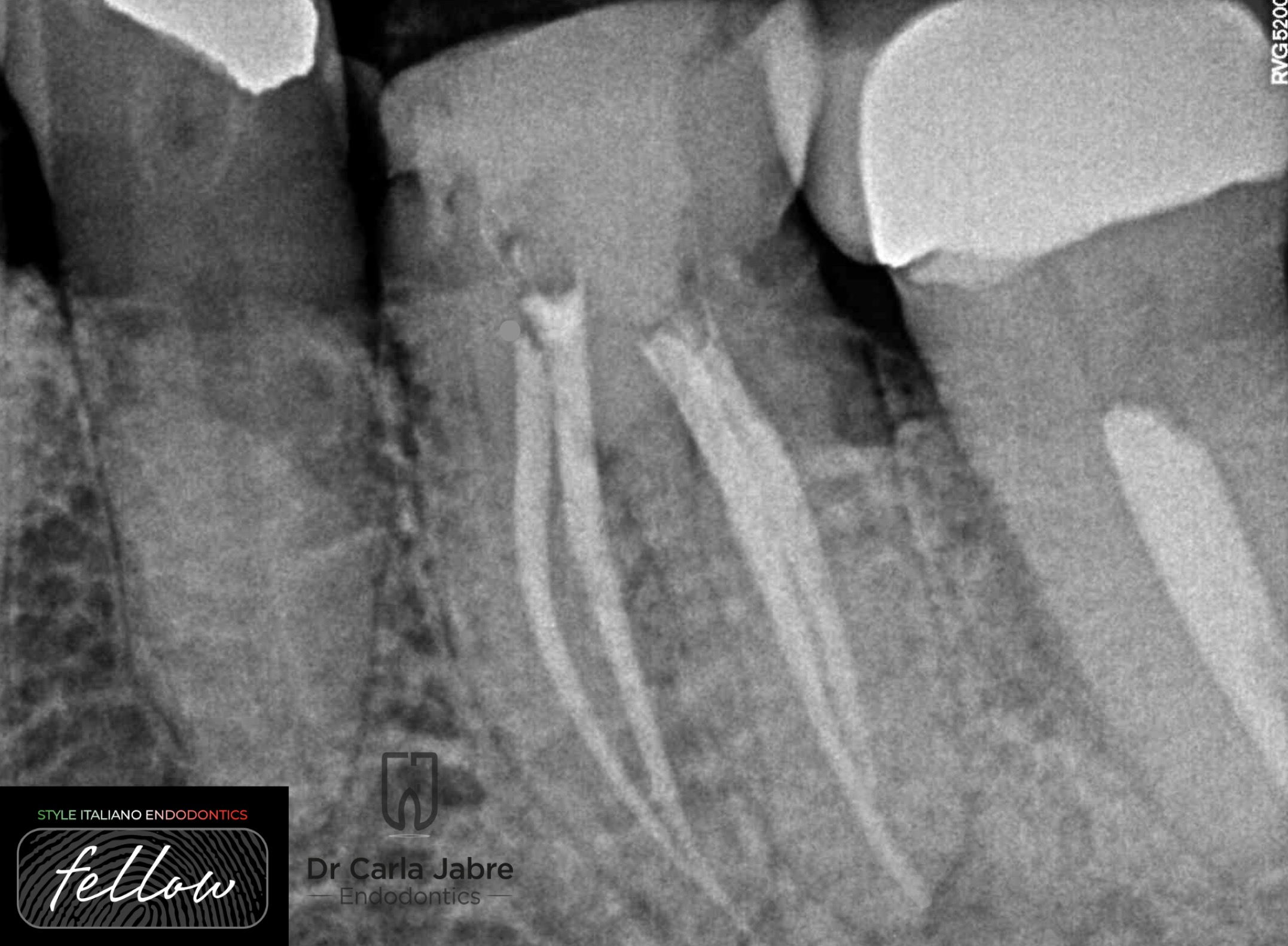

A periapical radiograph reveals a cavity under an old composite filling, a retracted pulp chamber and root canals, and a widening of the PDL apically.

Cold test and percussion were negative. Mobility and probing were within normal ranges.

In elderly patients, due to the increased bulk of dentine and pulpal fibrosis, a false negative response to vitality tests could lead the clinician into a false diagnosis. So other supporting evidence should be present to justify the need for treatment (3). In this case, the presence of the apical reaction and the deep cavity did not complicate much the diagnosis.

The previously described changes in the pulpo-dentinal complex may explain the absence of symptoms during the development of this cavity before pulp necrosis (2).

Fig. 2

Back and joint pain can make long procedures difficult to tolerate. Older patients can have difficulty reclining fully due to joint degeneration and changes in blood pressure regulation. Therefore, to make sessions easier, pillows can be placed under the neck for more comfort.

Bite blocks also help the patient relax their jaws without the need to strive to keep their mouth open. Otherwise, fatigue and tremor might develop. (3)

At the end of the session, a slow gradual return to a sitting position is important to avoid orthostatic hypotension. (2)

Fig. 3

For access cavity preparation, the use of magnification and lighting (in this case, loupes with x3 magnification) is mandatory.

Some steps were followed to make the access cavity preparation safer:

To start, a conventional access cavity outline was defined using high speed diamond burrs. This step helps staying centered and avoid over enlargement while searching for the canals.

On the initial radiograph, measuring the depth of the pulp chamber from the occlusal surface, and using a periodontal probe while drilling, helps staying in the “safe distance” and avoiding pulp floor perforation.

An important tool is a sharp endodontic probe, like the DG-16 (HuFriedy), that helps identify the pulp space once reached by feeling a sticky spot (3). It is important to know that no aspiration will be felt at this point.

Then, diamond burrs were replaced with ultrasonic tips because they allow better visualization. A diamond coated tip was used, along with the DG16, to refine the access cavity and find the 4 canals.

Stopping and observing the access cavity is important, because it allows the clinician to see the glassy translucent pulp stones and remove them with ultrasonic tips, and to see the dark grooves of the pulp floor and localize canal orifices.

Fig. 4

For shaping, the following sequence was followed:

- Early preflaring with a 25/.06 instrument approximately 4 mm in the canals to remove coronal interferences.

- Progressing apically while reducing the size of the instrument (20/.04 and 15/.02) until a 10 k file could passively reach WL.

- Glide path at WL and shaping up to size 25/.06

The goal is to progressively remove coronal interferences to allow a 10 k file to reach passively the apex. The use of mechanical NiTi files in a crown down technique is recommended for elderly patients because it was shown that it is a time saving technique and a reproducible one in difficult anatomies such as constricted canals (1,2,3,4).

During the shaping procedure, canals were always filled with sodium hypochlorite that acted like a lubricant for the instruments.

Fig. 5

The continuous wave of condensation technique was used for obturation.

Access cavity was sealed with a temporary filling, and the patient scheduled with the prosthodontist to complete the treatment.

Fig. 6

2008-2013: Undergrad studies at the faculty of Dentistry at Saint Joseph University, Beirut, Lebanon.

2013-2016: Masters in Endodontics at the faculty of Dentistry at Saint Joseph University, Beirut, Lebanon.

2018-2019: Masters in Biomaterials at Saint Joseph University, Beirut, Lebanon.

Dr Jabre has been a clinical instructor, guiding undergraduate students, in the department of Endodontics at Saint Joseph University, since 2016.

She is a member of the Lebanese Society of Endodontics, and a fellow in the Style Italiano Endodontics group.

Her private practice is limited to endodontics.

Conclusions

In conclusion, when treating elderly patients, extra care has to be given for patient’s comfort for them to be able to be cooperative during the whole session. The practitioner should also chose the correct technique and tools that allow a fast, but most importantly a safe and predictable outcome.

Bibliography

1)Al Rahabi MK. Root canal treatment in elderly patients. Saudi Med J 2019; Vol. 40 (3); 217-223.

2) Johnstone M, Parashos P. Endodontics and the ageing patient. Australian Dental Journal 2015; 60:(1 Suppl): 20–27.

3) Finbarr Allen P, Whitworth M. Endodontic considerations in the elderly. Gerodontology 2004; 21; 185–194.

4) Machado R, Silva EJ, Vansan LP. Constricted canals: a new strategy to overcome this challenge. Case Rep Dent. 2014:564106. doi: 10.1155/2014/564106.