Treat the invisible canal: a clinical challenge

20/01/2025

Marc Kaloustian

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

During primary treatment, even in simple cases, many root canal anatomy alterations and errors can occur such as access cavity over enlargement, perforations, blocage or file breakage. Sometimes, many iatrogenic issues combine and complicate the decision making. Central incisors retreatments are particular because of the esthetic aspect of these teeth that will motivate the practitioner and the patient to try to keep them for as long as possible in a patient’s mouth.

This case study will analyze a case of an upper left central incision retreatment with many technical errors such as a buccal perforation done during access preparation without taking care of the tooth rotation, a separated file in the middle part of the canal, another lateral mesial perforation that occurred after an unsuccessful trial of bypassing the instrument and an apical blockage.

Fig. 1

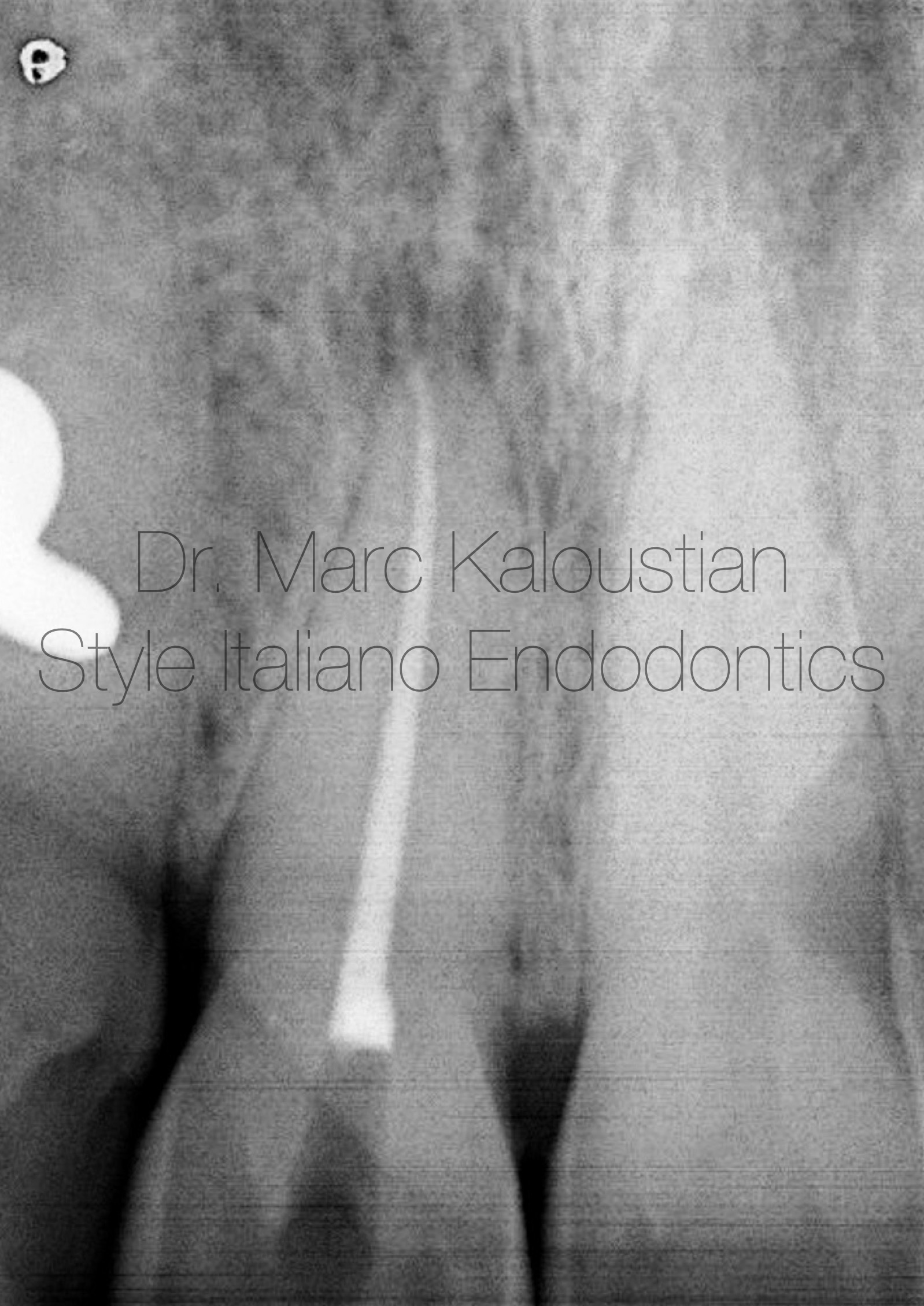

Upon clinical examination an upper right central (11) showed a discoloration, the tooth was asymptomatic. A peri-apical radiograph revealed a calcified canal with suspicion of a lesion from endodontic origin.

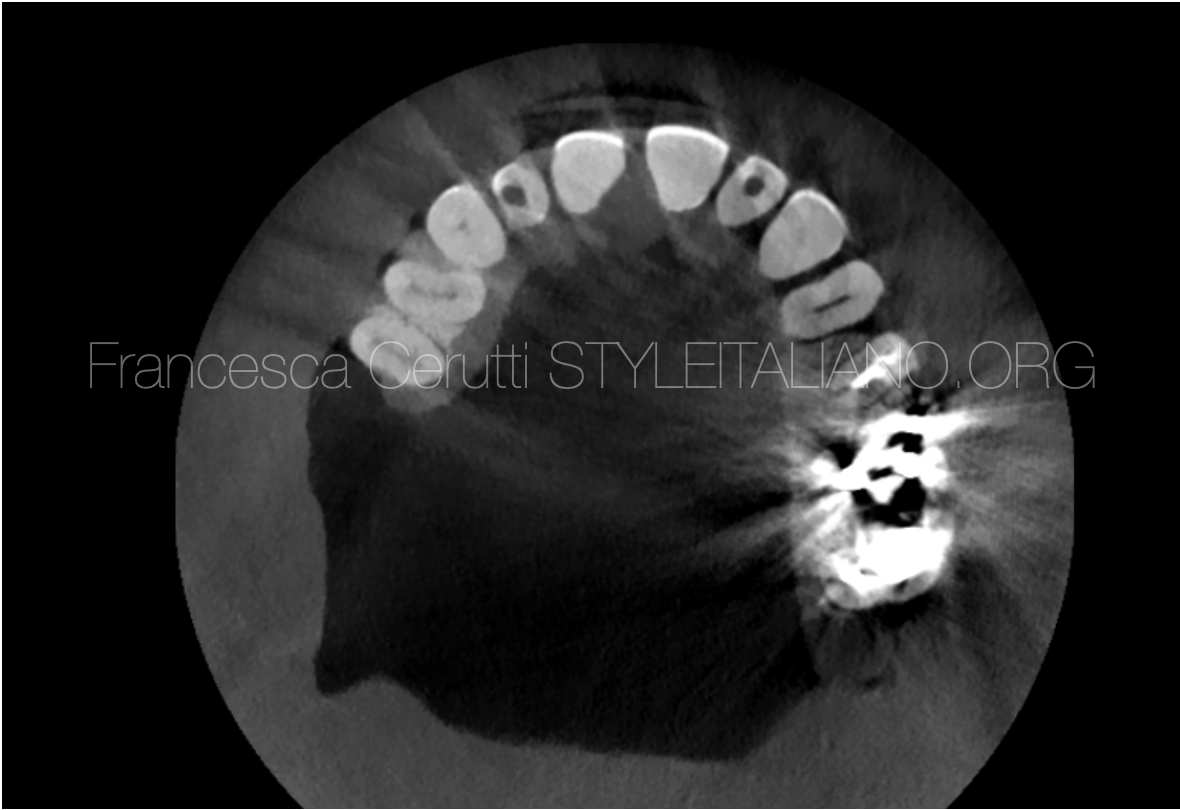

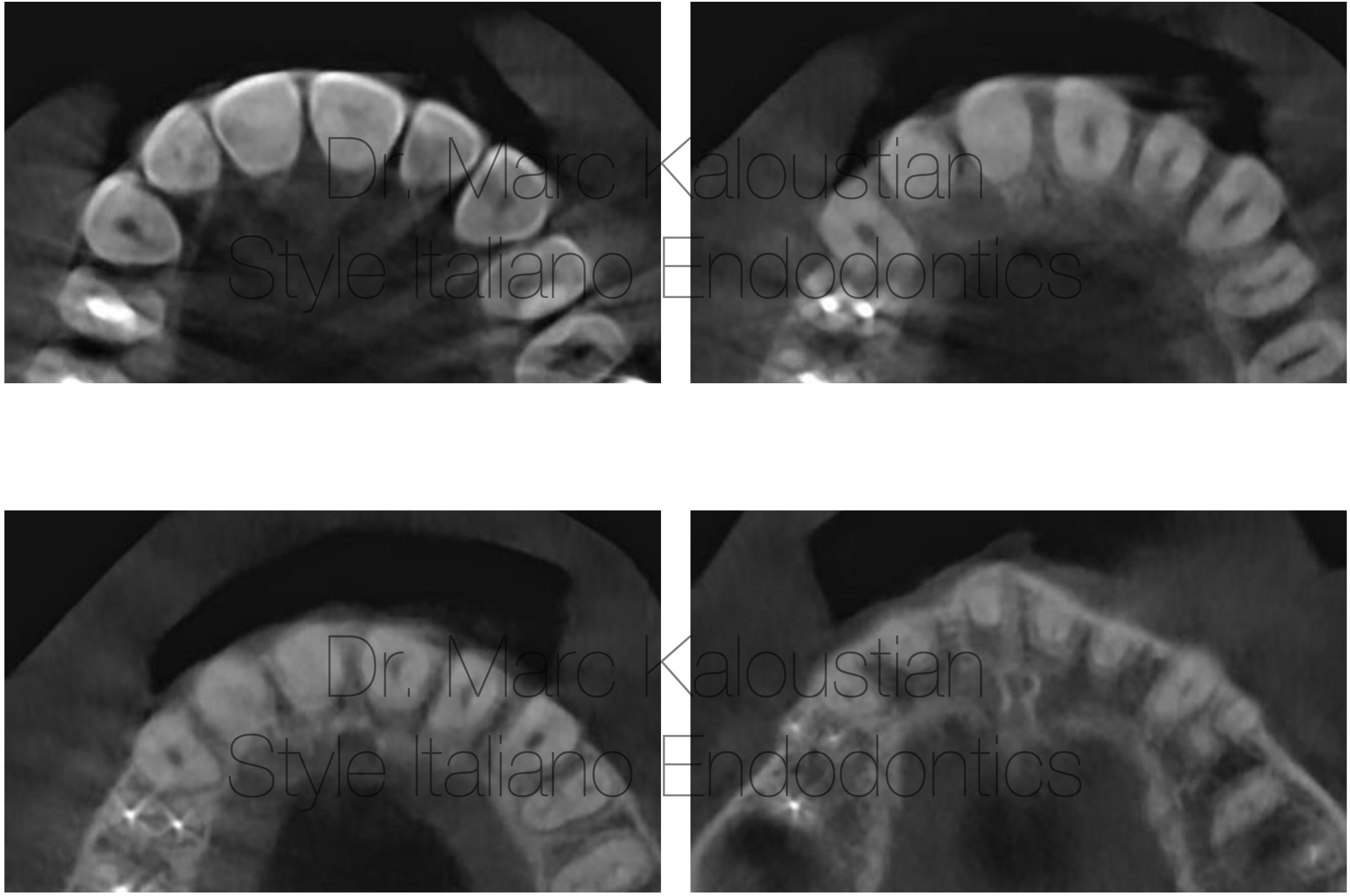

Fig. 2

A CBCT confirmed the canal obliteration and the presence of a peri-apical periodontitis.

Fig. 3

The axial view at different levels showed the high degree of calcification.

Fig. 4

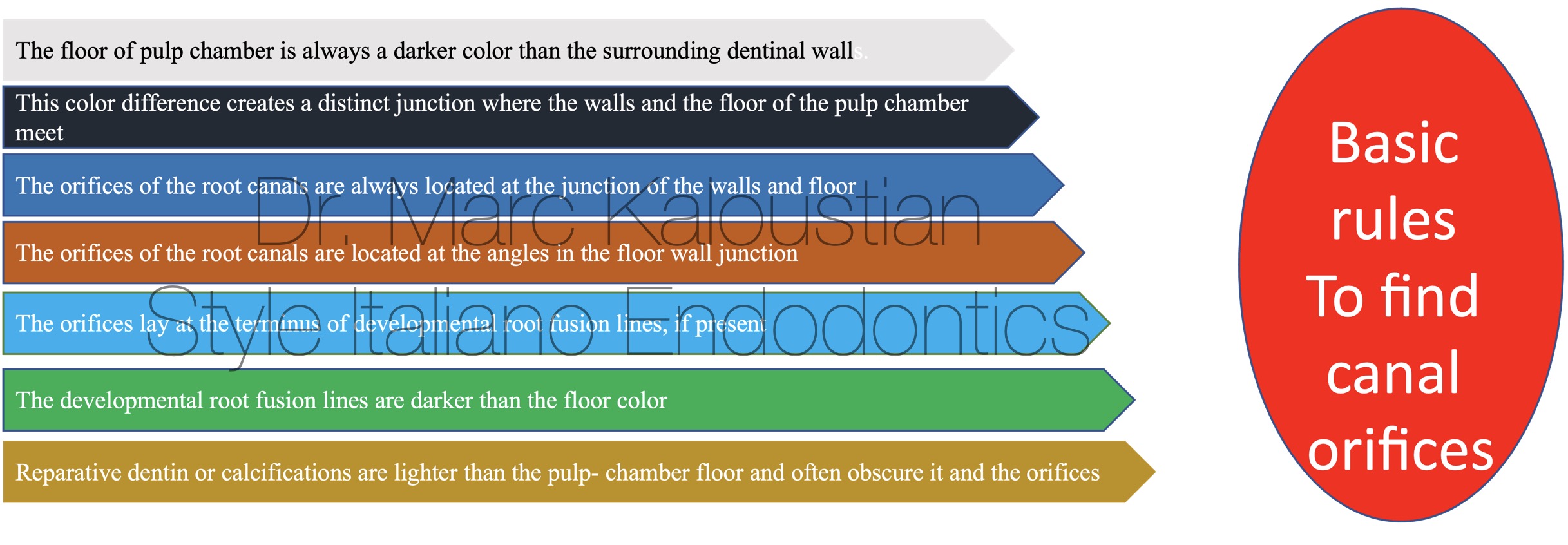

The decision of performing a root canal treatment was taken with the informed consent of the patient. The basic rules to find canal orifices in cases of calcification were applied.

In cases of calcified canal, a single tooth isolation can jeopardize the access to the canal orifice. In this case, the clamp was placed on the first premolar to allow a better clinical and radiographic visibility.

The access was initiated with a long surgical carbide bur used on high speed.

An ultrasonic non coated tip was first used for deeper preparation without water for better visibility, followed by a diamond coated ultrasonic tip used with irrigation for precise refinement and debris removal.

Fig. 5

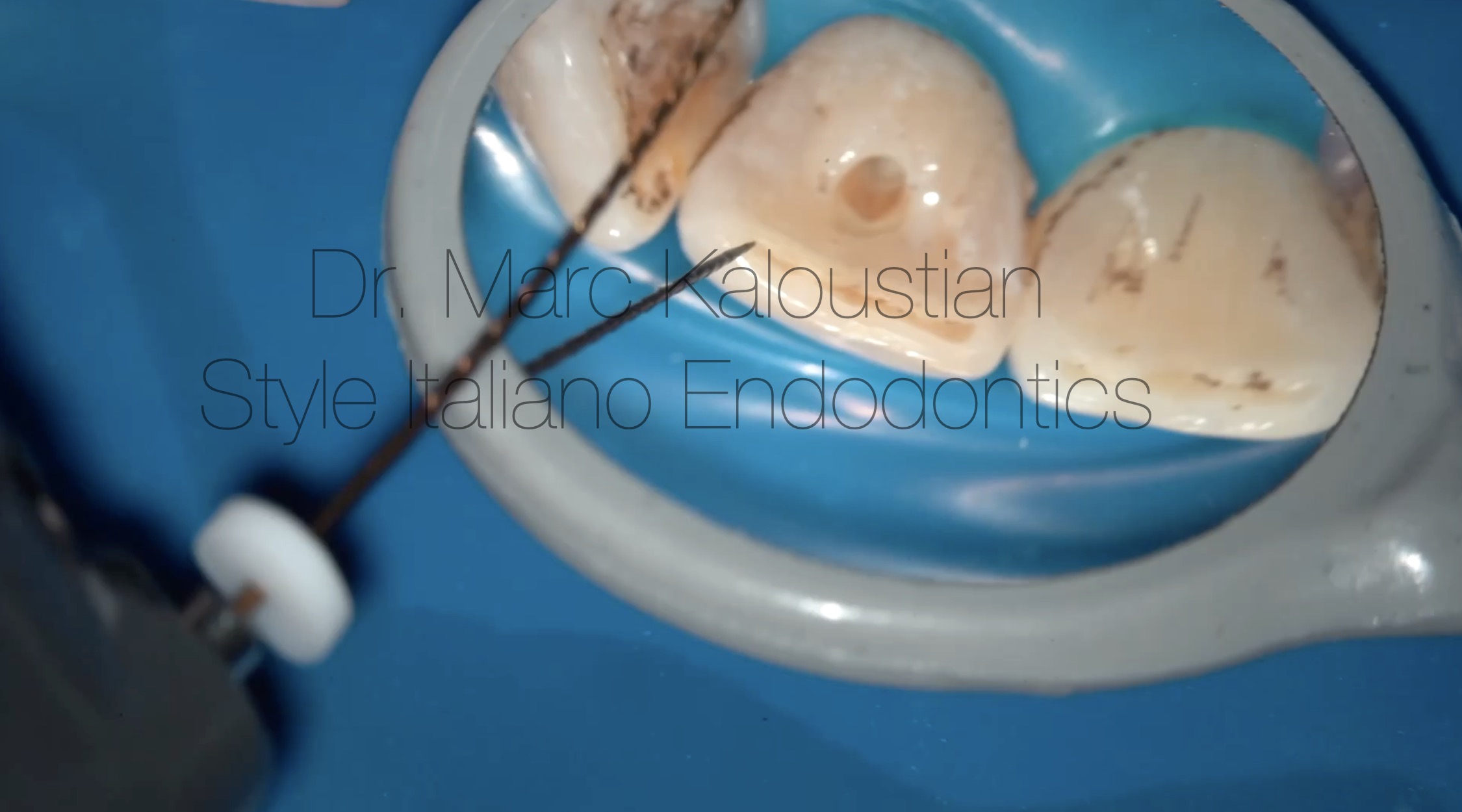

A periodical X-ray was taken to double check the proper direction of the drilling after the use of the bur and the ultrasonic tips.

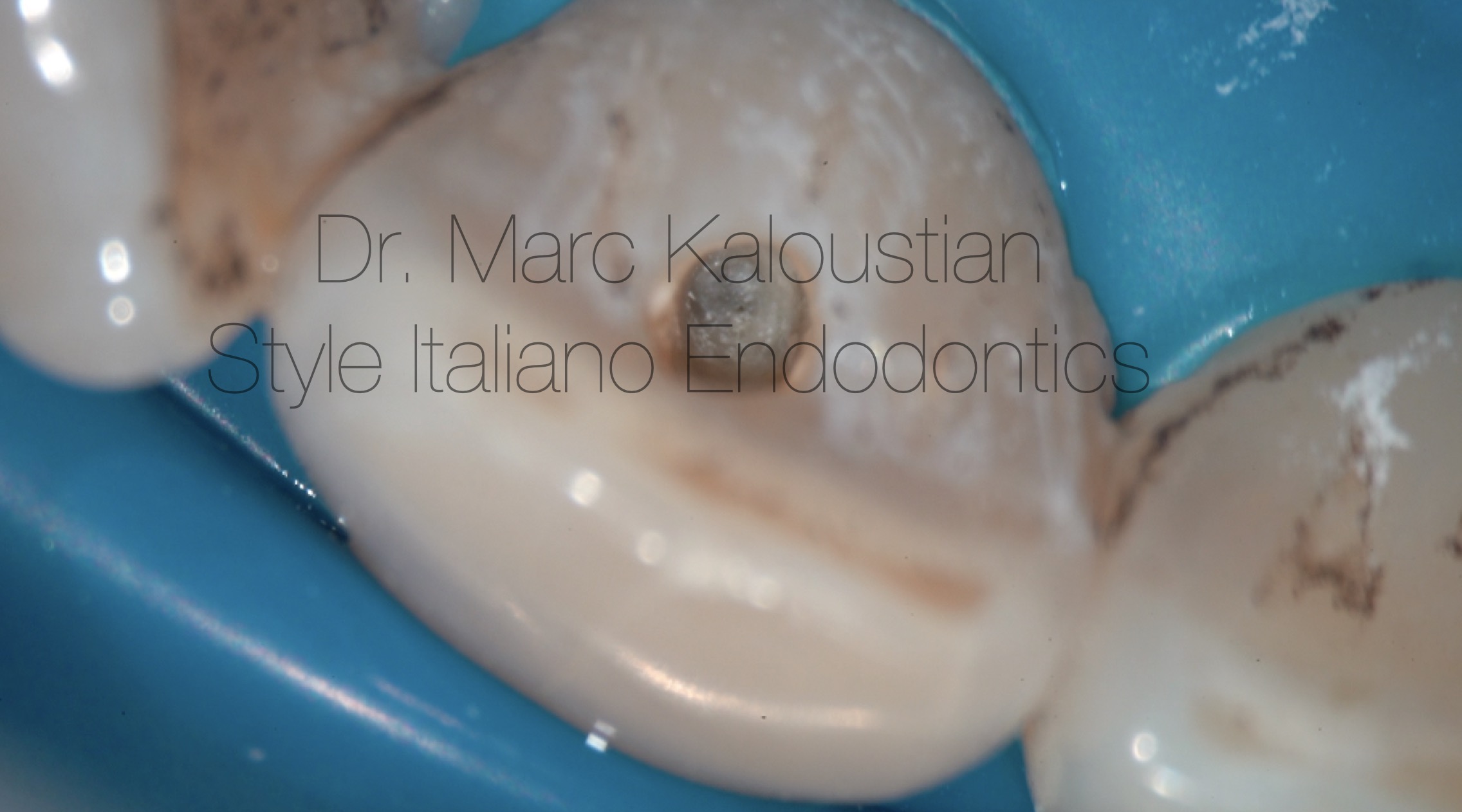

A small orifice surrounded by brown calcified tissue was detected at mid root on high magnification.

Fig. 6

A photo of the small orifice detected at mid root on high magnification.

Fig. 7

A special handfile handle was used with 06 C file to explore the orifice. The handle was then removed and a watch winding motion was applied to the file that progressed for few mm.

Fig. 8

A periapical radiograph was taken to verify the good direction of the file

Fig. 9

A glide path file 14/04 was used till first resistance to remove the small coronal interferences, followed by 31 mm, 10 K file that reached passively the foramen. The preliminary working length was recorded with the apex locator.

The same glide path file was now used till the preliminary working length, followed by a 15, 31 mm K file that reached the foramen. The final working length was recorded using the apex locator.

The canal length was 23 mm.

Fig. 10

A photo of the canal orifice after glide path.

The canal was shaped with a single heat treated NiTi file 25/06 in 2 steps. 12 cc of NaOCl 5.25 % was used with IrriFlex needle during the shaping procedure.

A 1 minute activation of the irrigation solution was applied with an ultrasonic tip.

Cone fit was done and tug back verified.

Fig. 11

A radiograph with the gutta-percha cone was taken.

3 cc of 17 % EDTA were delivered in the canal and activated with an ultrasonic tip for 1 minute. After irrigation with 3 cc of sterile water, the canal was dried with a micro-suction tip and paper points. The paper point test confirmed the final working length.

The canal was obdurated with bioceramic passive injection and gutta-percha cones.

Fig. 12

A radiograph after obturation was taken.

Conclusions

The treatment of calcified teeth remains one of the most challenging aspects of endodontic practice, particularly when it comes to the creation of an access cavity and the shaping of the root canals.

The creation of an access cavity in calcified teeth requires careful planning and precision. Unlike in non-calcified teeth, where the access cavity is straightforward, calcified teeth necessitate advanced diagnostic tools like cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and digital radiography to assess the extent of calcification and guide the clinician in preparing the access opening. The goal is to preserve as much healthy tooth structure as possible while ensuring adequate access to the canal system. A well-planned access cavity is crucial for both the successful removal of calcified material and for preventing iatrogenic damage to the tooth.

In this case, a technique based on the use of ultrasonic under high magnification was applied to find the canal orifice. Other techniques such us guided static or dynamic endodontics can also be used.

In conclusion, the management of calcified teeth, from access cavity preparation to canal shaping, has seen significant improvements due to ongoing advancements in technology and technique. With the right approach, clinicians can successfully treat calcified teeth, preserving natural dentition and ensuring long-term success for patients.

Bibliography

Andreasen F.M., Zhijie Y., Thomsen B.L., Andersen P.K. Occurrence of pulp canal obliteration after luxation injuries in the permanent dentition. Endod. Dent. Traumatol. 1987;3:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1987.tb00611.

Chaniotis A., Ordinola-Zapata R. Present status and future directions: Management of curved and calcified root canals. Int. Endod. J. 2022;55((Suppl. 3)):656–684. doi: 10.1111/iej.13685.

Fonseca Tavares W.L., Diniz Viana A.C., de Carvalho Machado V., Feitosa Henriques L.C., Ribeiro Sobrinho A.P. Guided Endodontic Access of Calcified Anterior Teeth. J. Endod. 2018;44:1195–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2018.04.014.

McCabe PS, Dummer PM. Pulp canal obliteration: an endodontic diagnosis and treatment challenge. Int Endod J. 2012 Feb;45(2):177-97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01963.

Robertson A., Andreasen F.M., Bergenholtz G., Andreasen J.O., Norén J.G. Incidence of pulp necrosis subsequent to pulp canal obliteration from trauma of permanent incisors. J. Endod. 1996;22:557–560. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(96)80018-5.

Silva E.J.N.L., De-Deus G., Souza E.M., Belladonna F.G., Cavalcante D.M., Simões-Carvalho M., Versiani M.A. Present status and future directions—Minimal endodontic access cavities. Int. Endod. J. 2022;55((Suppl. 3)):531–587. doi: 10.1111/iej.13696.