Radix entomolaris and paramolaris

15/02/2024

Diana Ibrahim ElSanour

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

The primary goal of root canal treatment is to thoroughly clean and shape the root canal system before a dense filling material. Furthermore, being aware of the complexities of root canal morphology contributes to the success of root canal therapy. It is well documented that mandibular molars frequently exhibit multiple anatomical differences in the number of roots and root canals. This poses as an endodontic dilemma for the clinician with respect to diagnosis and subsequent treatment [1].

Carabelli in 1844 first mentioned a major anatomical variant of the two rooted mandibular first molar; a tooth with a third distolingual root named as the Radix Entomolaris (RE) [2]. If this root is placed buccally or mesio-buccally then it is called Radix Paramolaris (RP) [3].

The aetiology behind the formation of RE and RP has not been determined yet. Recent studies link its formation to racial genetic variables, environmental factors during odontogenesis, and the dispersion of an atavistic gene or polygenetic system [3]. The presence of an RE or an RP has clinical implications in endodontic treatment. An accurate diagnosis of these accessory roots can avoid complications of a ‘missed canal’ during root canal treatment [4].

The prevalence of supernumerary root in mandibular first molar is low in Caucasian, African (Egyptian), European and Indian populations, While it is the highest incidence with Mongoloid traits, such as Korean, Chinese, Eskimo, and Native American populations that may reach 33-40% [5].

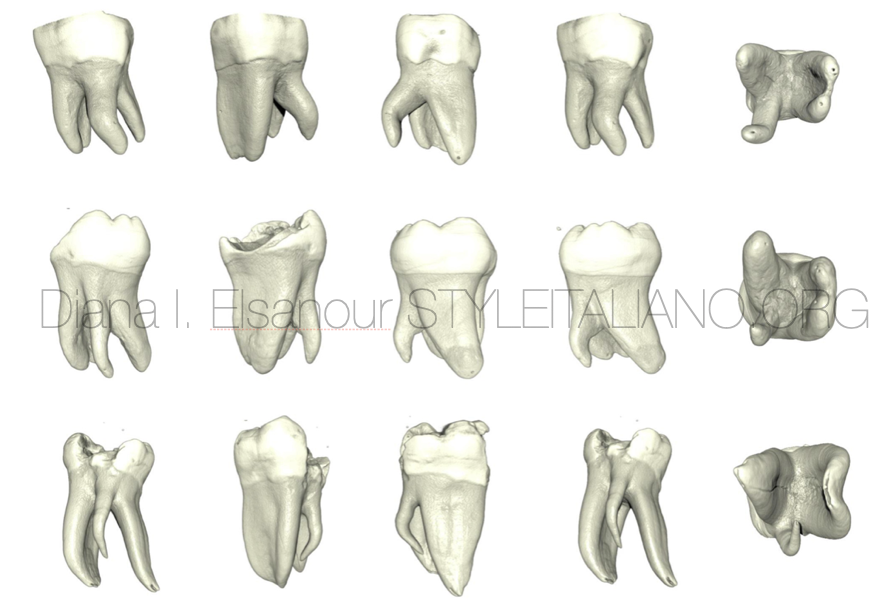

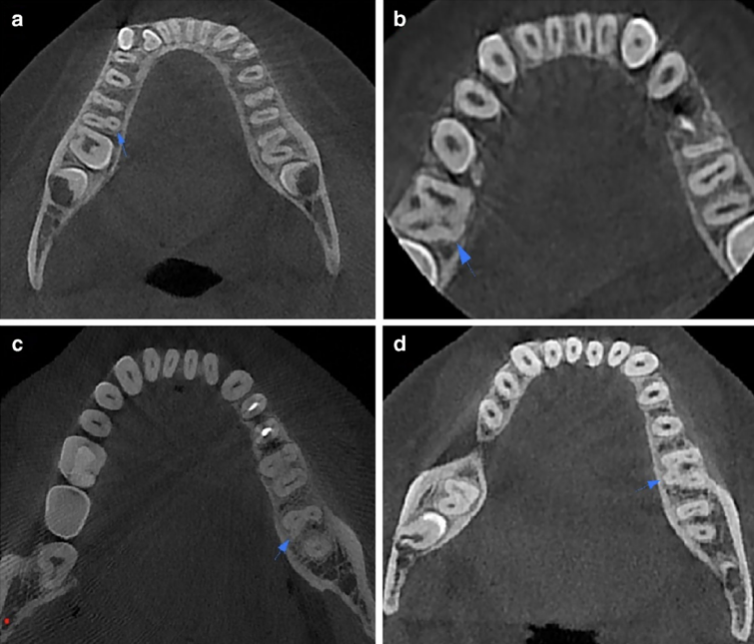

Fig. 1

Classification given by Carlsen and Alexanderson (1990) [6]

according to the location of the cervical part of the RE.

This classification allows for identification of separate and non-separate RE in conjunction with the location of the distal root.

Type A – Distally located cervical part with two normal distal root components.

Type B – Distally located cervical part but only one normal distal component.

Type C – Mesially located cervical part.

Type AC – Central location between mesial and distal root components.

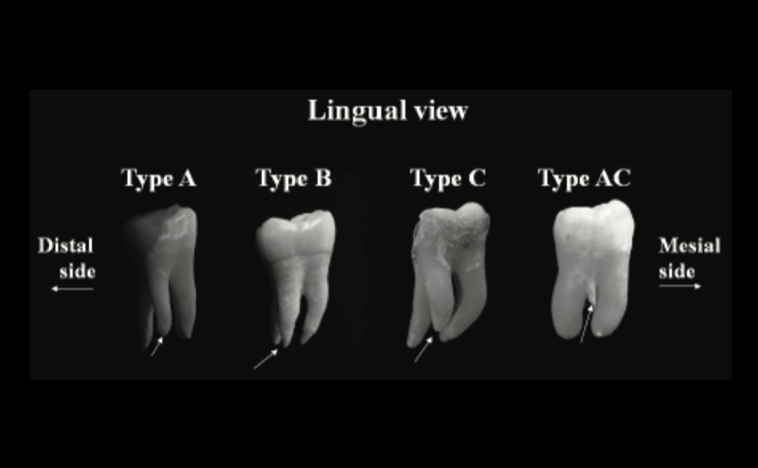

Fig. 2

De Moor et al (2004) [7]

classified RE-based on the curvature in buccolingual orientation into three types.

Type I – a straight root/root canal.

Type II – an initially curved entrance which continues as a straight root/root canal.

Type III – an initial curve in the coronal third of the root canal and a second buccally oriented curve starting from middle to apical third.

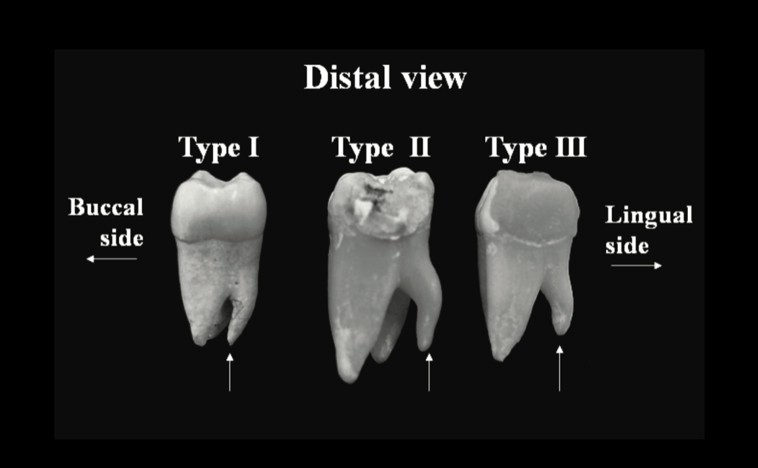

Fig. 3

Song et al. (2010) [8]

added two more newly defined variants of RE.

- Small – Length shorter than half of the length of the distobuccal root

- Conical – Smaller than the small type and having no root canal within it.

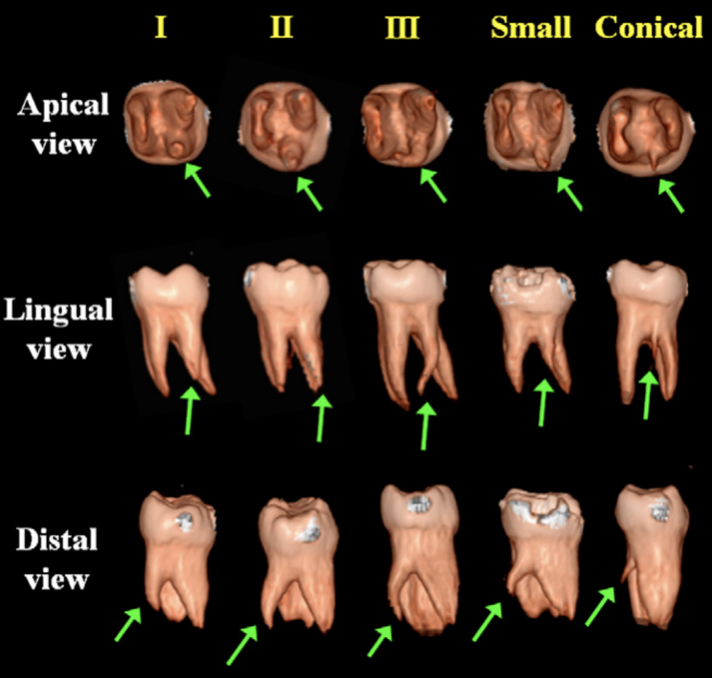

Fig. 4

Duman et al.(2020) [9]

according to the location of the cervical part on axial slices of CBCT images.

- Type A

- Type B

- Type C

- Type AC

Fig. 5

How to diagnose?

To reveal the RE, first, a second radiograph should be taken from a more mesial or distal angle (30 degrees). Second, clinical inspection of the tooth crown and analysis of the cervical morphology of the roots by means of periodontal probing can facilitate identification of an additional root. An extra cusp (tuberculum paramolare) or more prominent occlusal, distal or distolingual lobe, in combination with a cervical prominence or convexity, can indicate the presence of an additional root [4].

How to manage?

Regarding Access cavity: to avoid perforation or stripping in the coronal third of a severe curved root, care should be taken not to remove an excessive amount of dentin on the lingual side of the cavity and orifice of the RE [4].

Regarding root canal preparation; A severe root inclination or canal curvature, particularly in the apical third of the root (as in a type III RE), can cause shaping aberrations such as straightening of the root canal or a ledge, with root canal transportation and loss of working length resulting. The use of flexible nickel-titanium rotary files allows a more centered preparation shape with restricted enlargement of the coronal canal third and orifice relocation [4].

Nevertheless, unexpected complications such as instrument separation do occur, and are more likely to happen in an RE with severe curvature or narrow root canals.

Fig. 6

The (separate) RE is mostly situated in the same buccolingual plane as the distobuccal root, a superimposition of both roots can appear on the preoperative radiograph, resulting in an inaccurate diagnosis.

A thorough inspection of the preoperative radiograph and interpretation of particular marks or characteristics, such as an unclear view or outline of the distal root contour, can indicate the presence of a ‘hidden’ RE [4].

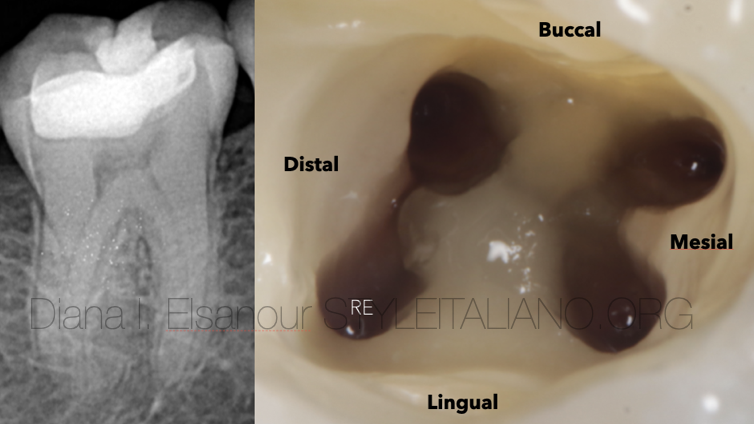

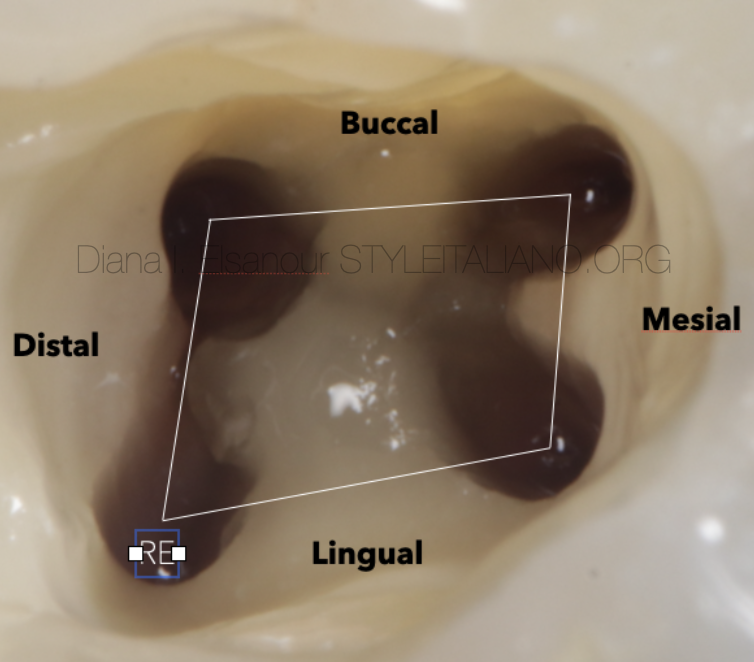

Fig. 7

The location of the orifice of the root canal of an RE has implications for the access opening. The orifice of the RE is located disto - to mesio-lingually from the main canal or canals in the distal root. An extension of the triangular access opening to the (disto) lingual results in a more rectangular or trapezoidal outline form.

Fig. 8

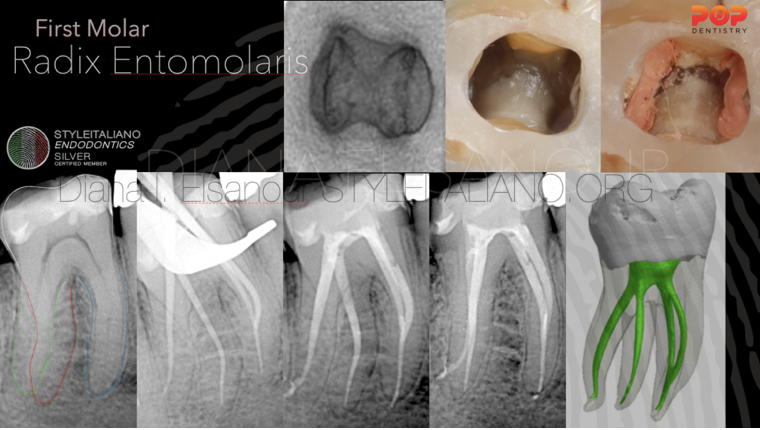

Clinical case n 1. Female 45 years-old. The presence of RE has been diagnosed at radiographic examination. After Access cavity, relocation and enlargement of the orifice of the RE, initial root canal exploration with small manual K-files (#8 and #10) together with radiographic estimation of working length and curvature determination, and the creation of a glide path before preparation, are step-by-step actions to avoid procedural errors.

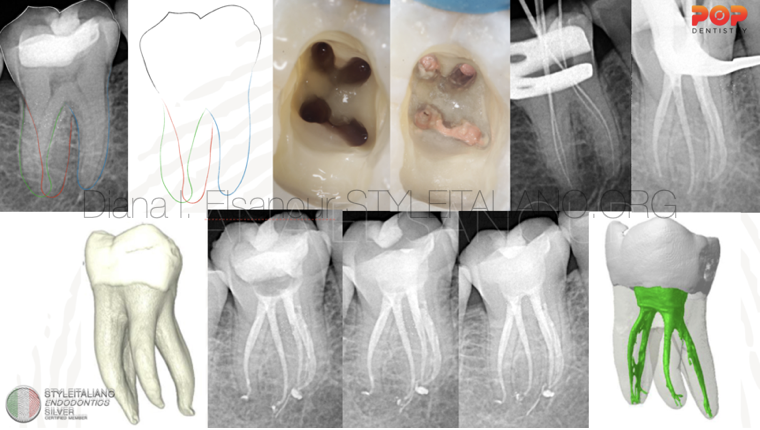

Fig. 9

Clinical case n 2. Male 50 years-old. The presence of RE has been diagnosed at radiographic examination (Red line) due to unclear view or outline of the distal root contour and the root canal. Intraoperative Rxs are useful to better understand the anatomy of mesial canal configuration and RE.

Fig. 10

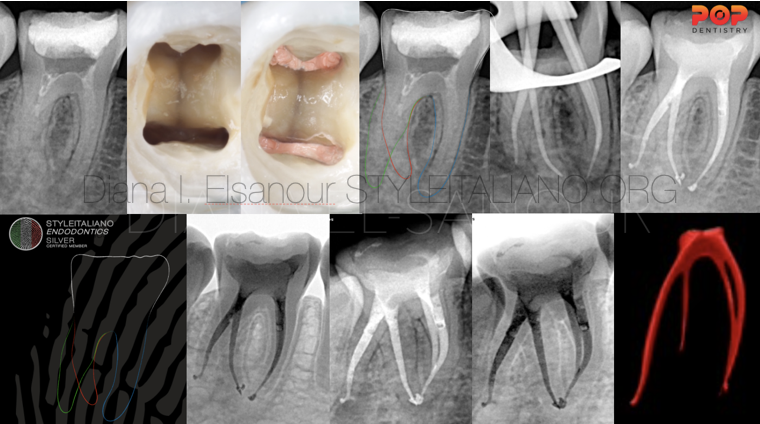

Clinical case n 3. Female 25 years-old. The presence of RE has been diagnosed and confirmed preoperatively from radiography.

Fig. 11

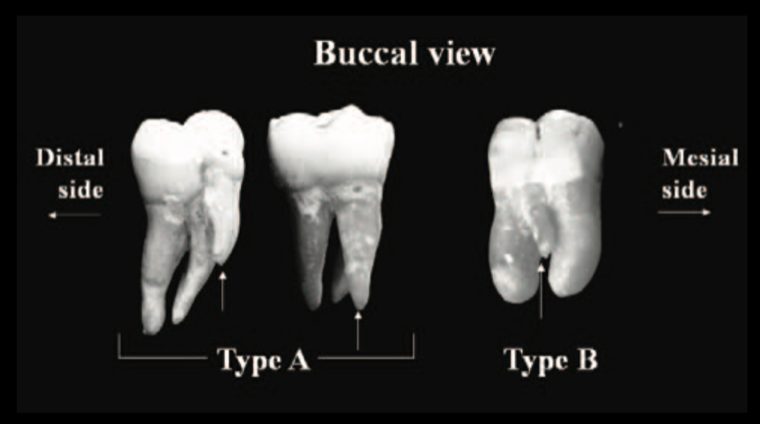

Carlsen and Alexandersen (1991) [10]

classified RP into two different types

- Type A - Cervical part is located on the mesial root complex

- Type B - Cervical part is located centrally between the mesial and distal root complexes.

Fig. 12

Clinical case n 4. Male 27 years-old. The presence of RP has been diagnosed at radiographic examination, negotiated and treated.

Conclusions

- The frequency of a RE in mandibular molars varies in accordance with specific racial traits. The incidence of a RP is very rare and occurs less frequently than the RE.

- Clinicians should be aware of the unusual root morphology in mandibular first molars.

- Pre-operative diagnosis of RE and RP is essential to avoid procedural errors that may compromise the root canal treatment result.

- Radiographs should be taken at two different horizontal angles to identify and locate this extra root.

- Careful clinical inspection of tooth crown and cervical morphology is necessary.

- The access cavity must be modified in a distolingual direction in order to visualize and treat the RE, resulting in a trapezoidal access cavity.

Bibliography

- Mastoras K, Ioannidis K, Beltes P. Presence and clinical significance of radix entomolaris and radix paramolaris. Balkan Journal of Stomatology. 2010;14(1):16-22.

- Carabelli G. Systematisches Handbuch der Zahnheilkunde, 2nd ed. Vienna: Braumullerund Seidel, 1844; p 114.

- Bolk L. Bemerküngen über Wurzelvariationen am menschlichen unteren Molaren. Zeitung fur Morphologie und Anthropologie, 1915;17:605-610.

- Calberson FL, De Moor RJ, Deroose CA. The radix entomolaris and paramolaris: clinical approach in endodontics. Journal of endodontics. 2007;33(1):58-63.

- Hassan AA, Al-Nazhan S, Al-Maflehi N, Aldosimani MA, Zahid MN, Shihabi GN. The prevalence of radix molaris in the mandibular first molars of a Saudi subpopulation based on cone-beam computed tomography. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics. 2020;45(1).

- Carlsen O, Alexandersen V. Radix entomolaris: identifcation and morphology. Scand J Dent Res. 1990;98:363–73.

- De Moor RJ, Deroose CA, Calberson FL. The radix entomolaris in mandibular first molars: an endodontic challenge. International endodontic journal. 2004;37(11):789-99.

- Song JS, Choi HJ, Jung IY, Jung HS, Kim SO. The prevalence and morphologic classification of distolingual roots in the mandibular molars in a Korean population. Journal of endodontics. 2010;1:36(4):653-7.

- Duman SB, Duman S, Bayrakdar IS, Yasa Y, Gumussoy I. Evaluation of radix entomolaris in mandibular first and second molars using cone-beam computed tomography and review of the literature. Oral radiology. 2020;36:320-6.

- Carlsen O, Alexandersen V. Radix paramolaris in permanent mandibular molars: identification and morphology. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 1991 Jun;99(3):189-95.

- Souza-Flamini LE, Leoni GB, Chaves JF, Versiani MA, Cruz-Filho AM, Pécora JD, Sousa-Neto MD. The Radix Entomolaris and Paramolaris: A Micro–Computed Tomographic Study of 3-rooted Mandibular First Molars. Journal of endodontics. 2014;40(10):1616-21.