Management of Middle Mesial Canal in a lower Molar

27/01/2022

The Community

Warning: Undefined variable $post in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/styleendo/htdocs/styleitaliano-endodontics.org/wp-content/plugins/oxygen/component-framework/components/classes/code-block.class.php(133) : eval()'d code on line 2

Knowledge of both normal and abnormal anatomy of the root canal system dictates the parameters for execution of root canal therapy and can directly affect the outcome of the endodontic therapy. Missed extra roots and root canals are a major reason for failure of root canal treatment.

The lower mandibular first molar normally has two roots, one mesial and one distal with two canals in the mesial and one or two canals in the distal root. The literature cites the anatomic variations and abnormalities associated with lower first mandibular molars; variations in canals include C-shaped canals, five canals, six canals, and seven canals. Variations in roots like three rooted mandibular molars have also been reported.

Till date few clinical reports have described more than two canals in the mesial root of mandibular molars. Among these, the occurrence of middle mesial canal in the lower mandibular molar is (1–15%); this canal is also called “intermediary mesial canal” or “medial mesial canal” since it is situated centrally between the main buccal and lingual root canals. The diameter of these middle mesial canals is smaller than other two and is age related due to dentinal apposition. The mesial canal is called independent when a distinct coronal orifice and apical foramen were observed or confluent when converging to one of the other two main canals and terminating at a common foramen.

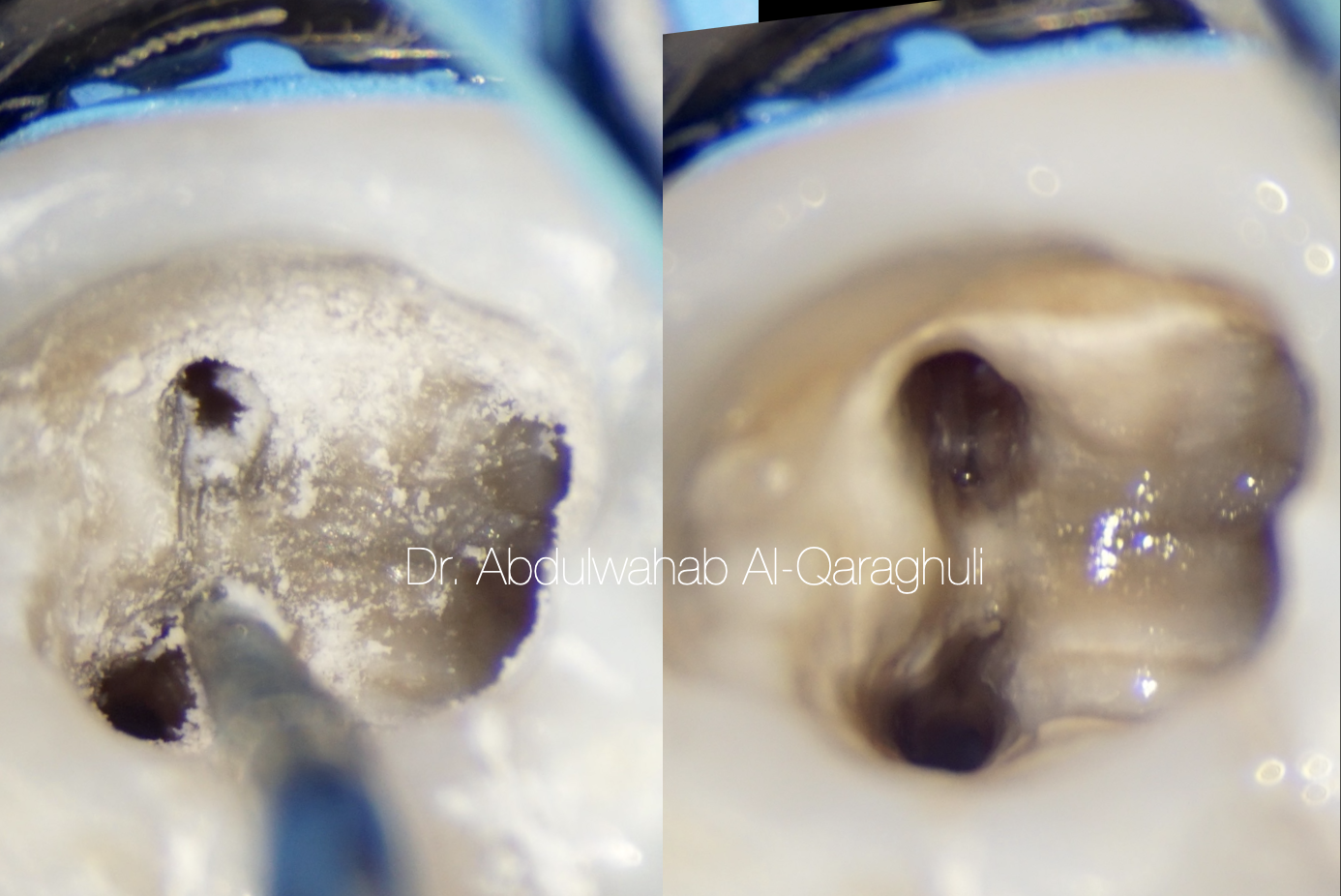

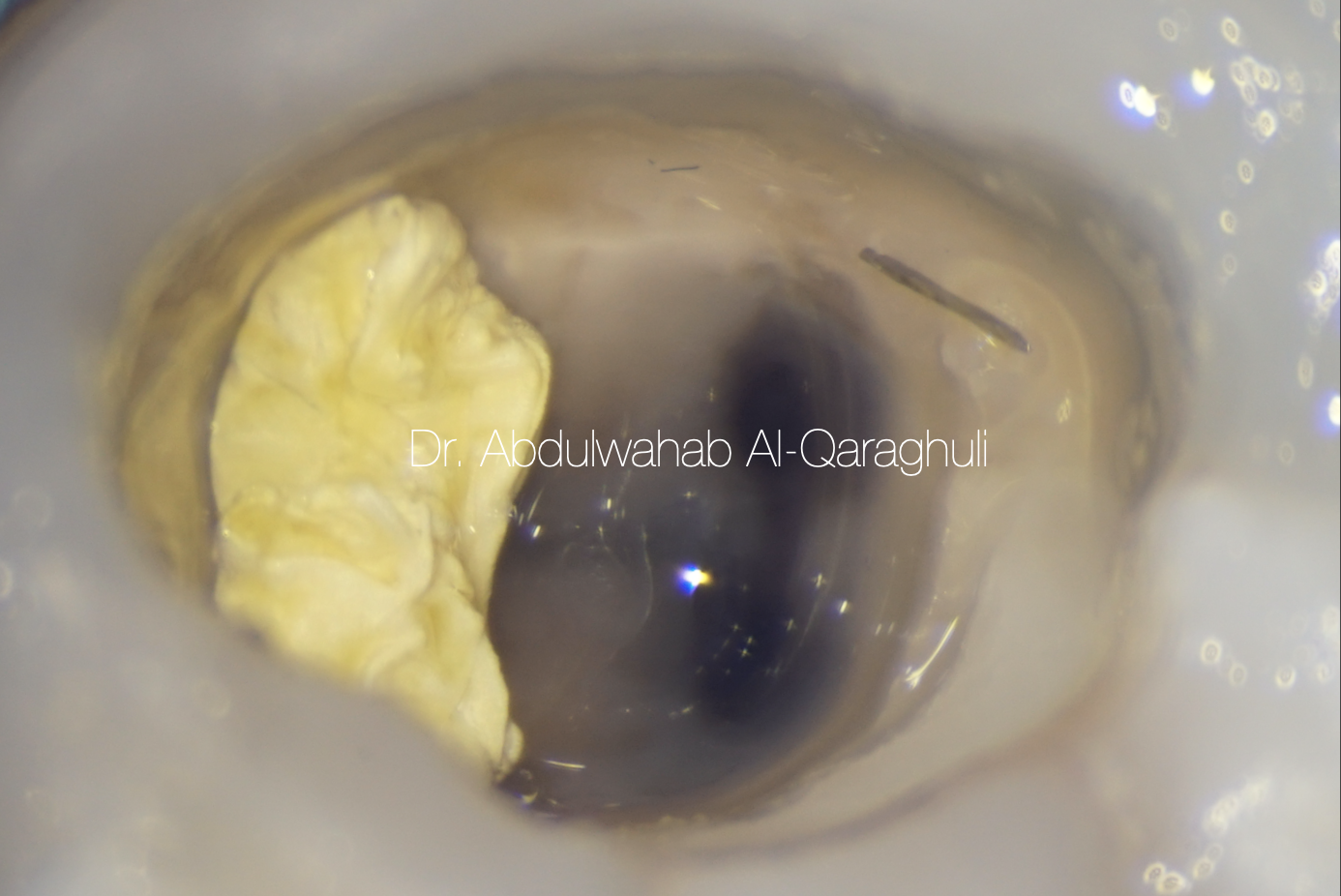

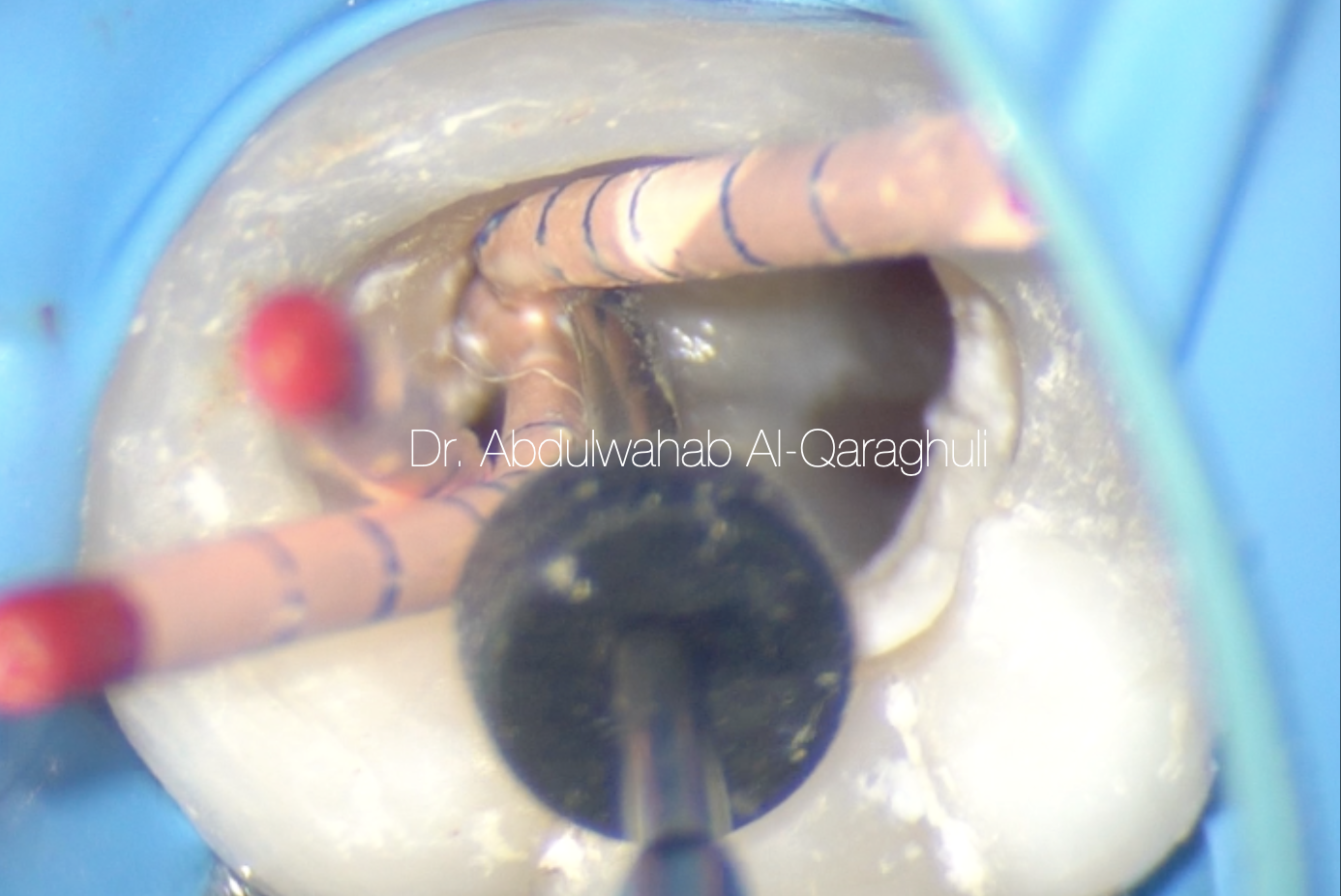

Fig. 1

Initial situation of lower 1st Molar with large gingival polyp presented with spontaneous pain

Fig. 2

Pre-op X-Ray showed deep carious lesion with periapical radiolucency

Fig. 3

Excessive gingival tissue removed by thermacut bur. The bur will cauterise the gingiva when cutting on high speed without the water spray

Fig. 4

This figure shows bleeding from the gingiva due to cutting of gingival polyp

Fig. 5

Gingival polyp was removed as a one piece

Fig. 6

This figure shows complete removal of gingival polyp, and tooth ready for isolation

Fig. 7

Isolation with rubber dam for pre-endo buildup, clean margin all around the tooth

Fig. 8

All carious tissue was removed and Access opening was made through the pulp chamber, a proper access cavity preparation is of central importance in localizing the orifices of the root canals

Fig. 9

Orifice opener to remove the coronal pulp tissue and to enlarge the canals orifices

Fig. 10

Removal of necrotic pulp tissue from the canals

Fig. 11

Starting the build up, using Circumferential matrix in order to restore the missing walls

Fig. 12

Pre Endo-buildup was done, and the tooth is ready for the next visit

Fig. 13

Temporary filling, End of the first visit

Fig. 14

Second visit, single isolation for accused tooth

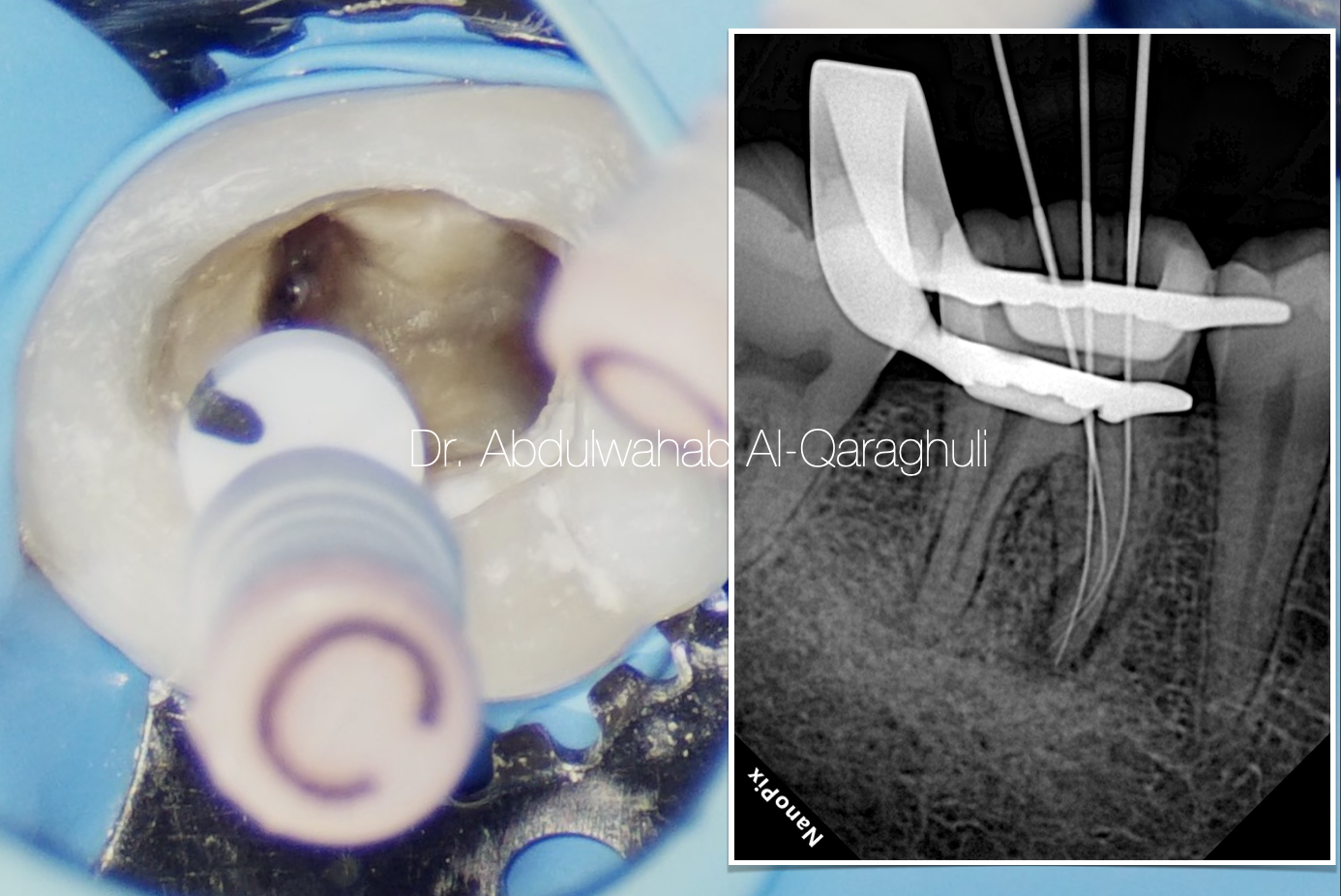

Fig. 15

Working length determination for the four canals

ML, MB, DL, DB

Fig. 16

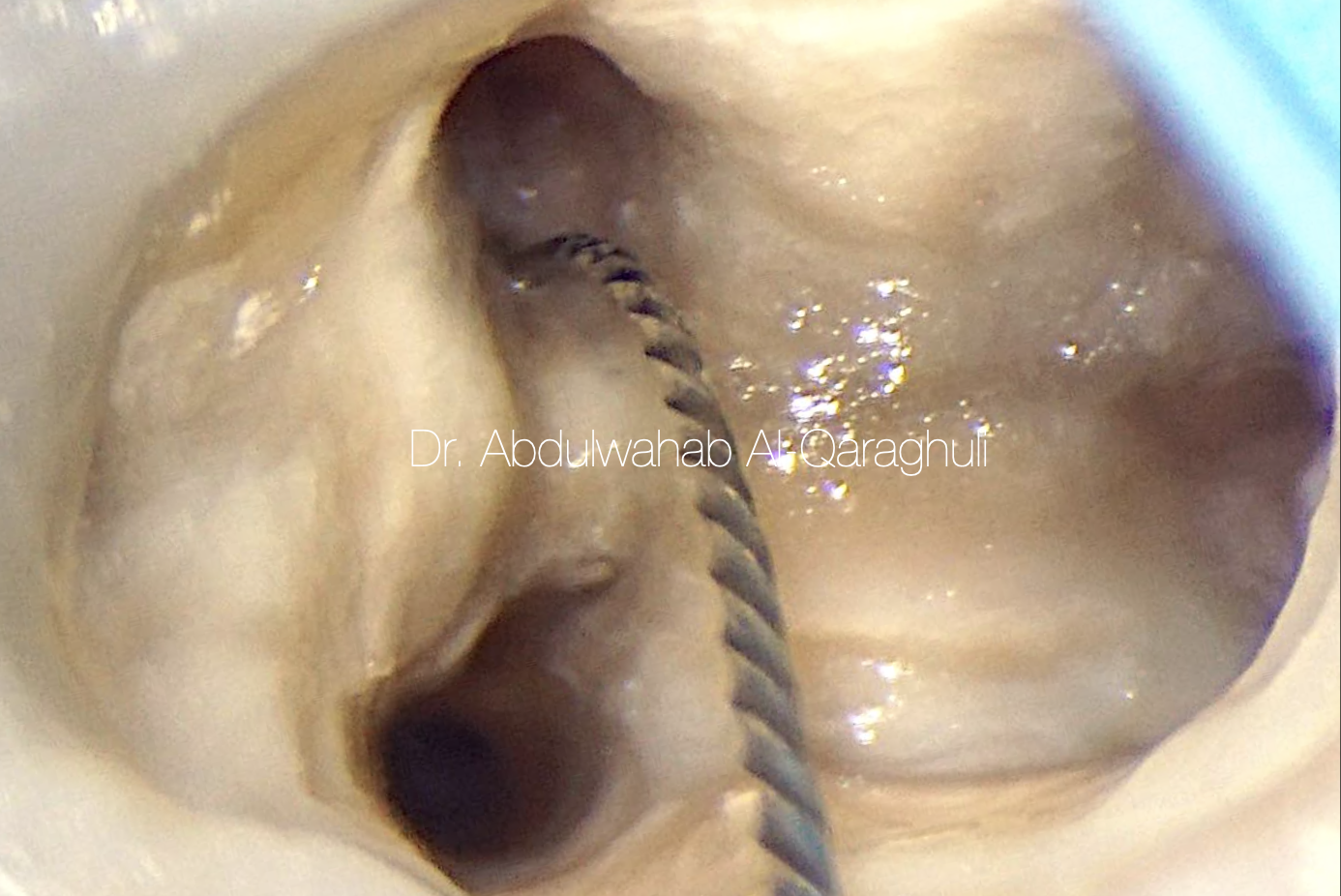

Shaping of the canals

Fig. 17

Searching for extra canal by manual file

Fig. 18

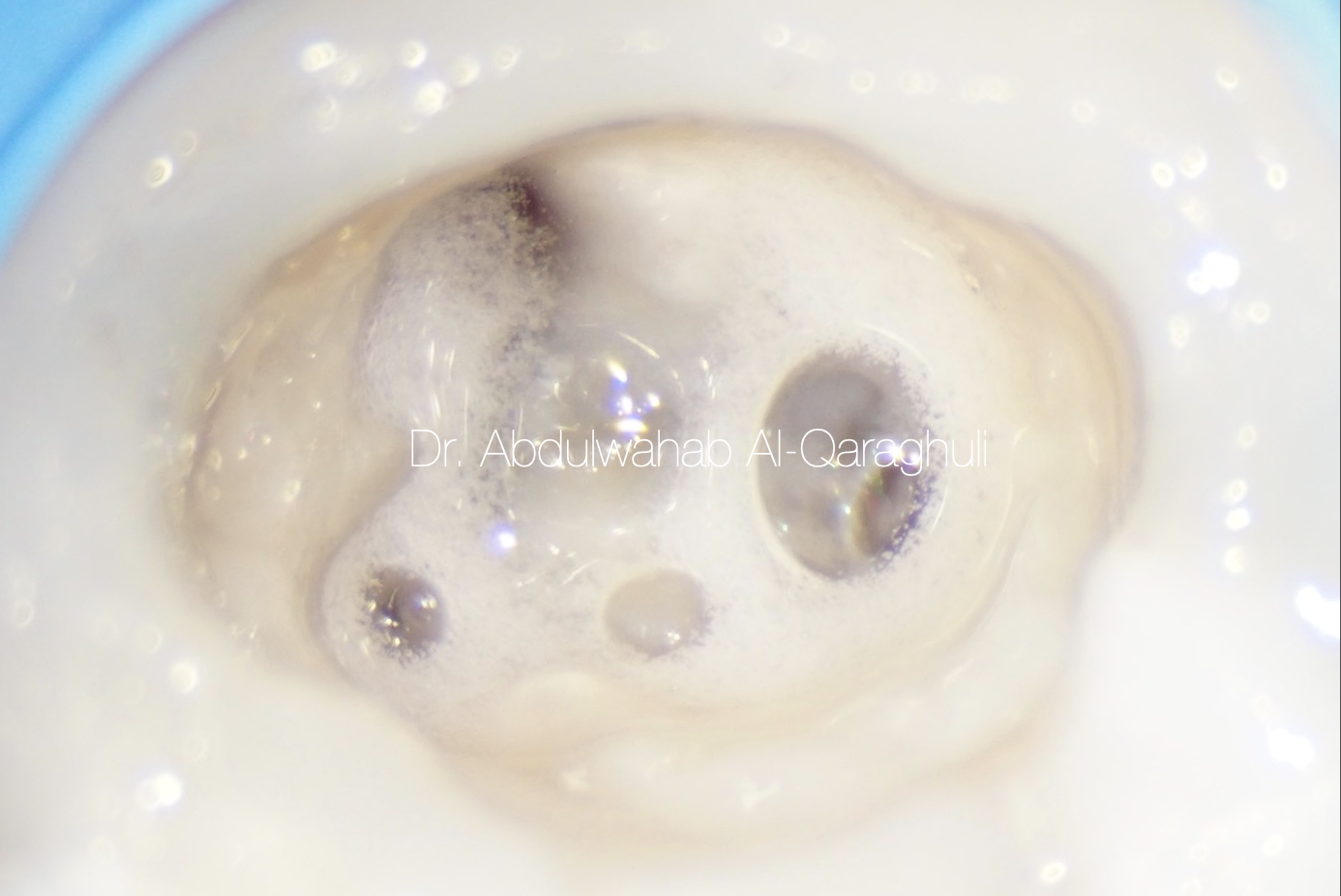

Cleaning of the isthmus by ultrasonic tips

In most of the cases, middle mesial canal is hidden by a dentinal projection in the mesial aspect of pulp chamber walls, and this dentinal growth is usually located between the two main canals (mesiobuccal-mesiolingual)

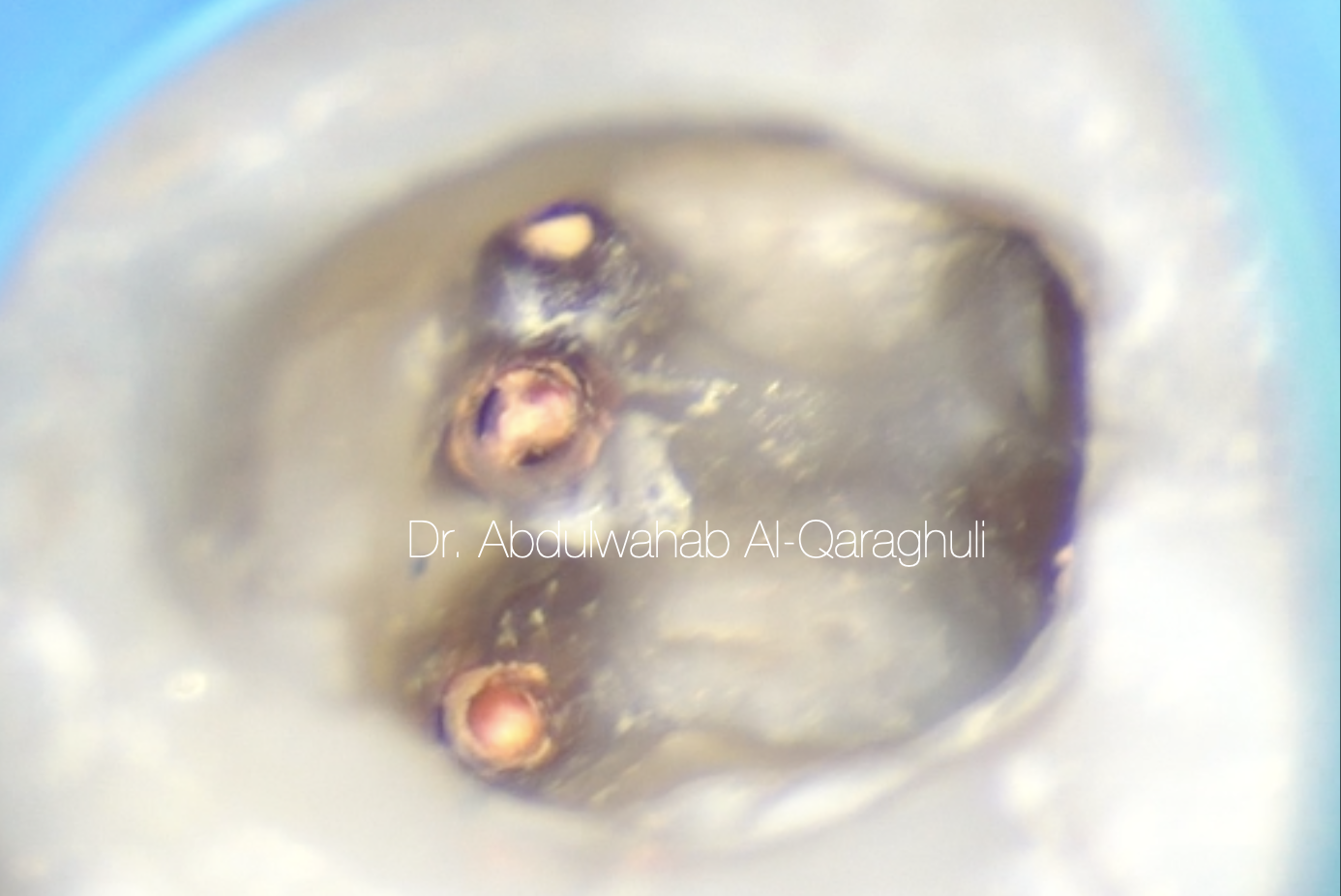

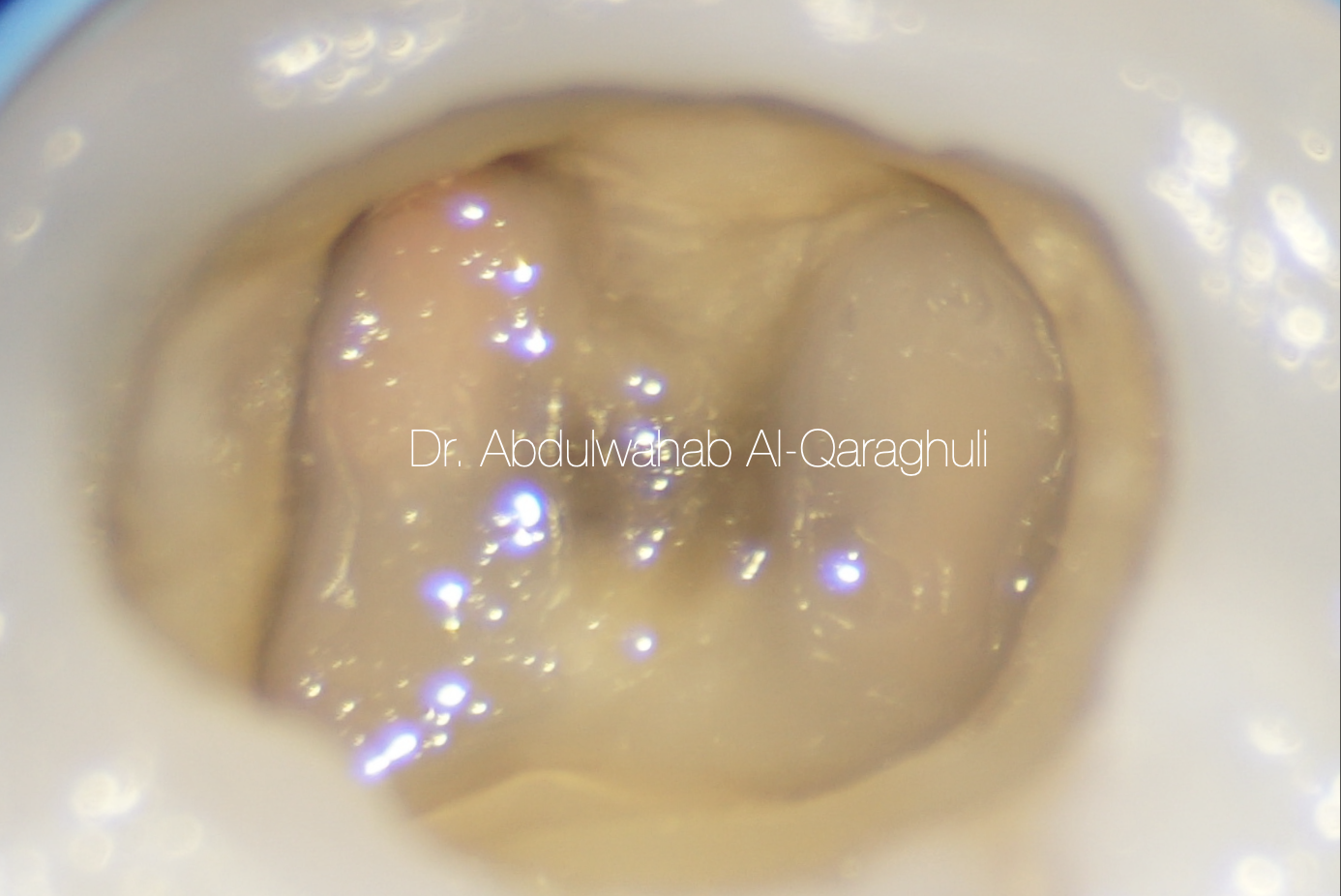

Fig. 19

MM (medio-mesial canal) was catched

The additional canal was explored with a no. 10 K-file

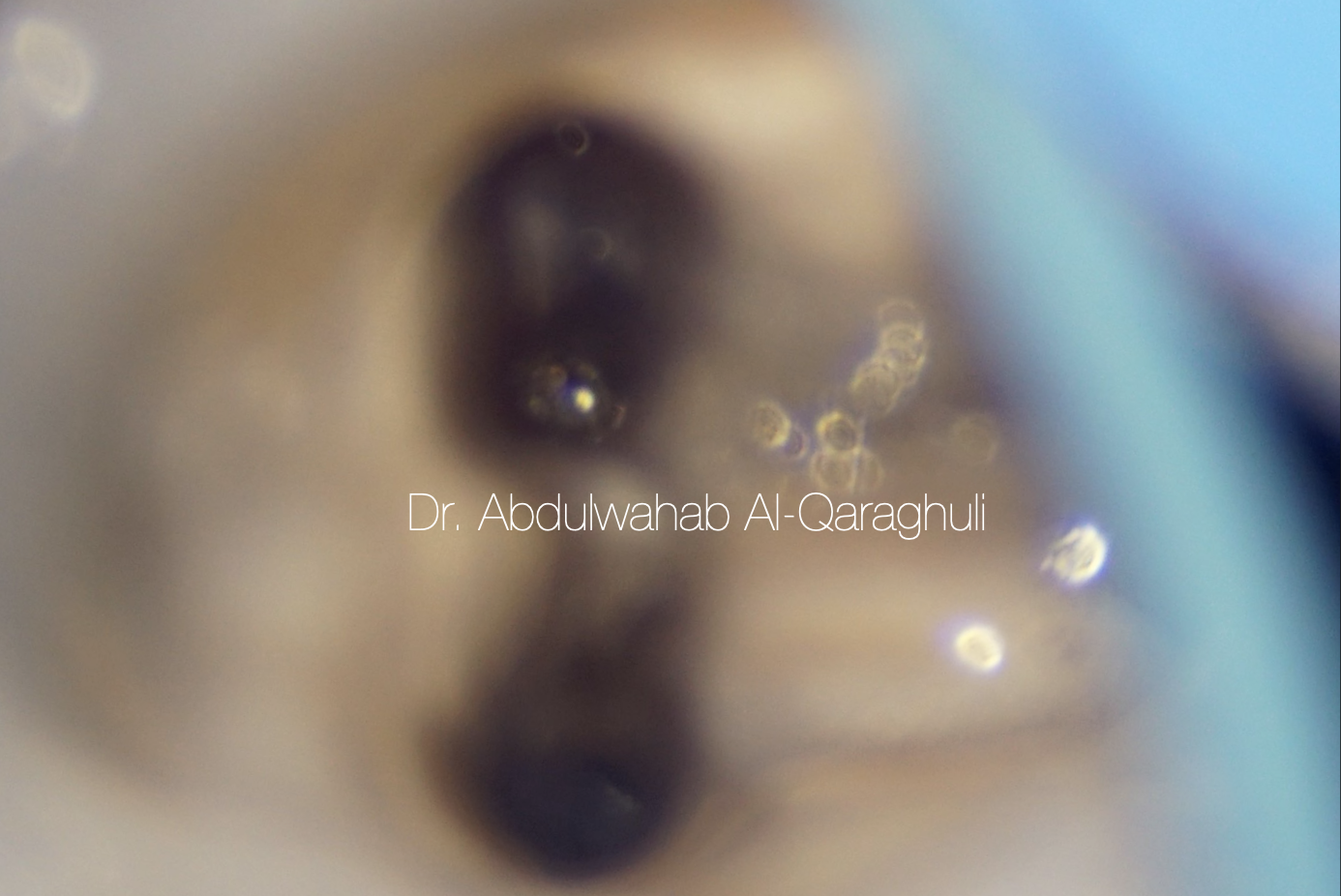

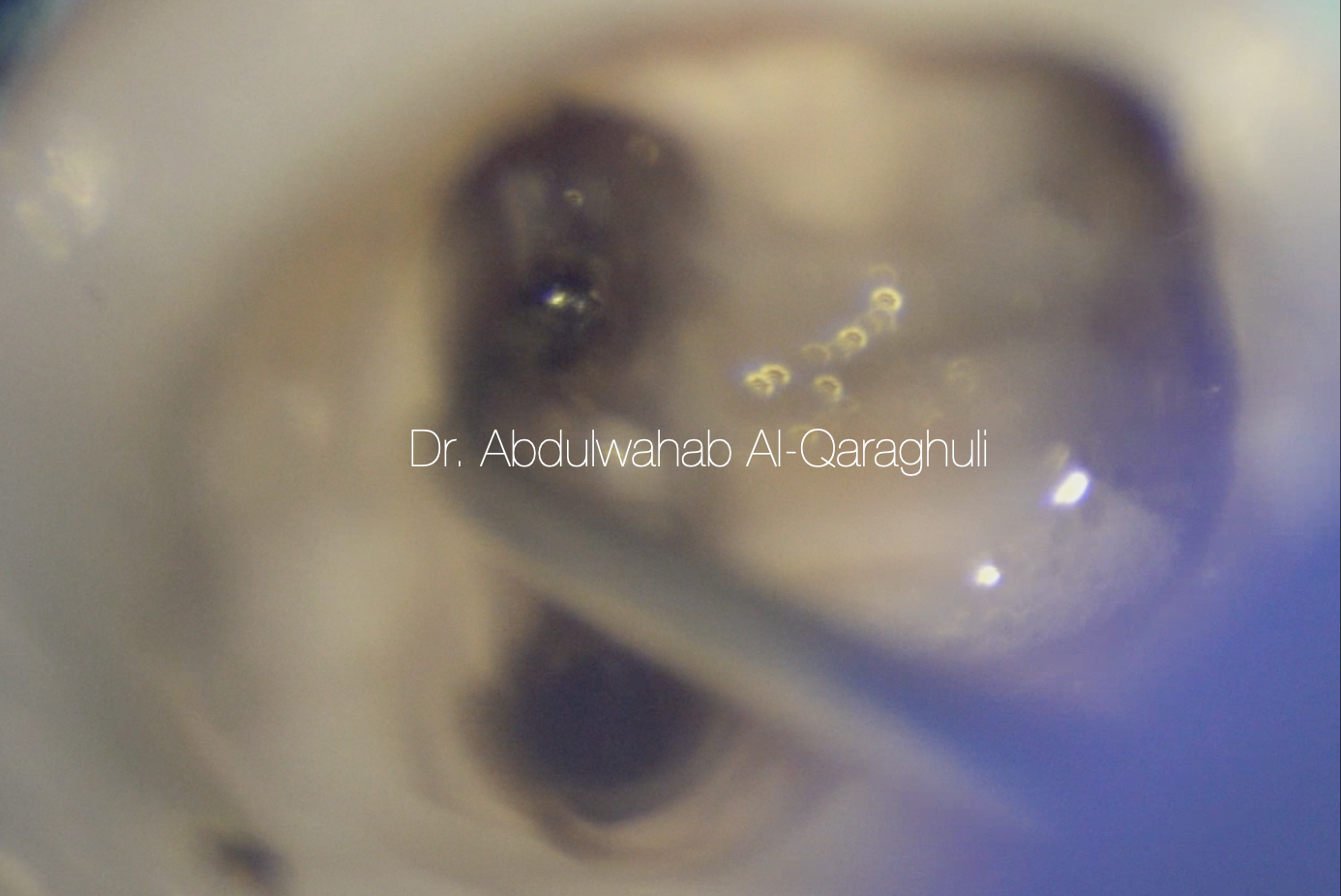

Fig. 20

No.10 K-file was separated during the negotiation of MM

Fig. 21

Ultrasonic tip to remove the separated instrument

Fig. 22

Separated instrument jumped from MM to Distal canal during removal

Note: I should have closed each canal orifices by teflon or liquid dam in order to prevent this mistake

Fig. 23

Separated file was successfully retrieved by ultrasonic tips

Fig. 24

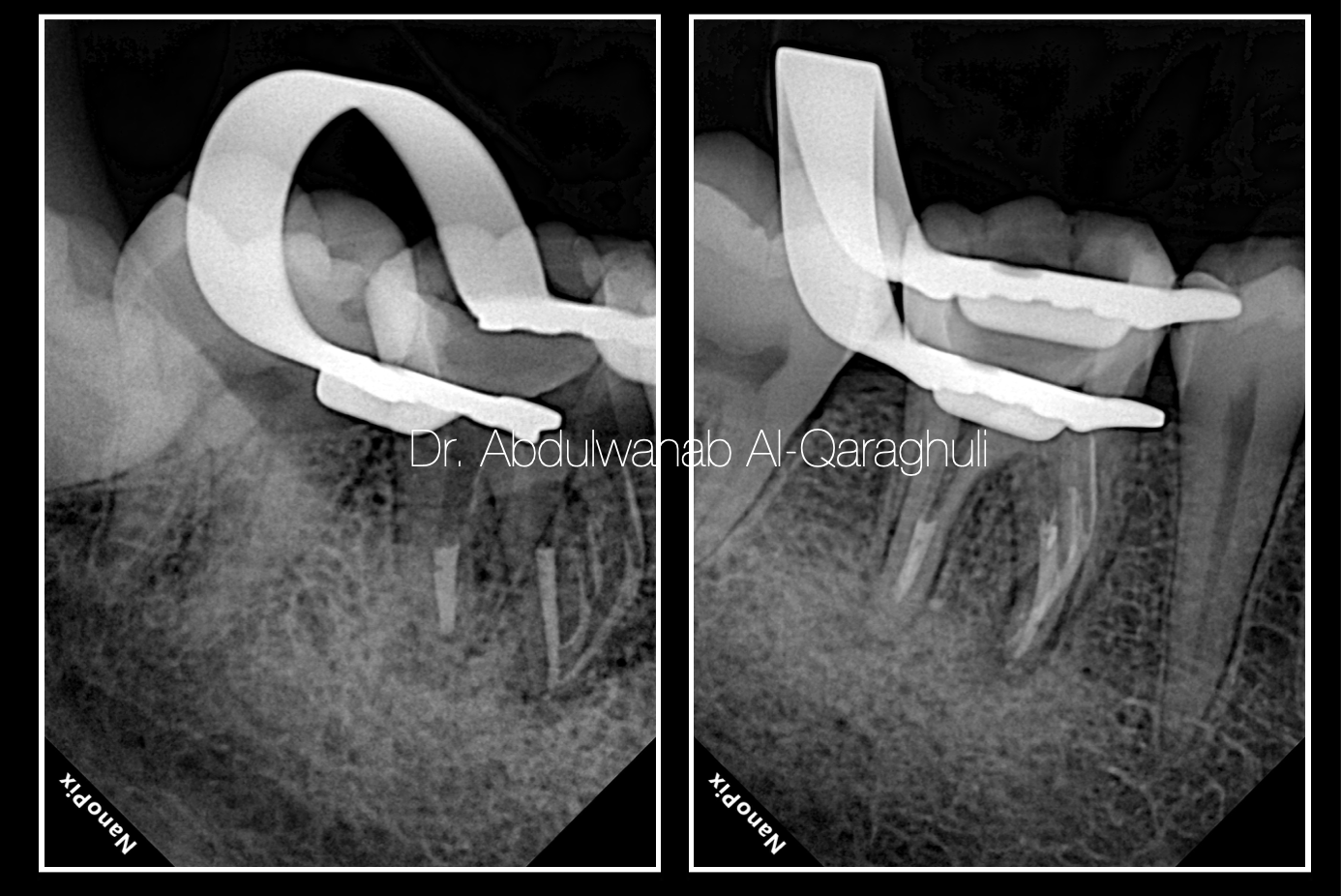

X-Ray to Confirm the complete separated instrument removal

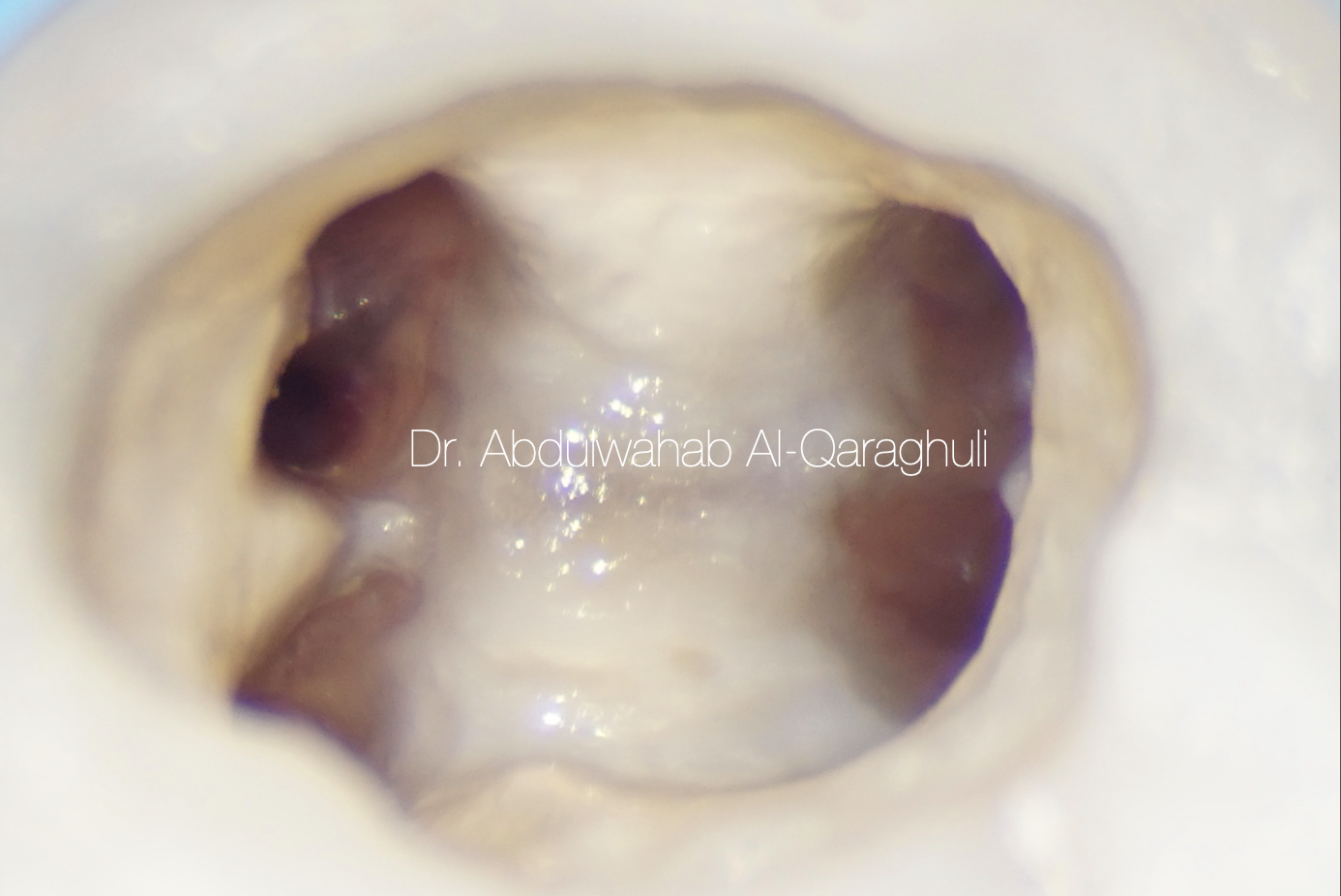

Fig. 25

Three files in mesial canal system

ML , MM , MB

Fig. 26

Final working length determination

Apical gauging

Apical gauging is a technique to best determine the size of the apical constriction and the taper of the apical portion closest to the foramen.

Apical gauging helps with:

1. Choosing the best master cone that closely matches canal length and taper

2.Achieving true tug back – as opposed to false tug back!

3.Minimising GP extrusions during obturation, especially with warm vertical compaction/condensation.

How do you do apical gauging?

Establish the depth of apical constriction – this is the zero reading on your apex locator. Remember your working length will be 0.5mm – 1mm short of this.

After cleaning and preparing the canal system to your working length, passively insert 02 taper hand files, starting from #15. If the file goes past the apical constriction (your working length + 0.5-1mm), then choose the next largest file and repeat.

When a file passively binds short of the apical constriction, that will be the upper limit of the apical constriction diameter. The smaller file before that would be the lower limit.

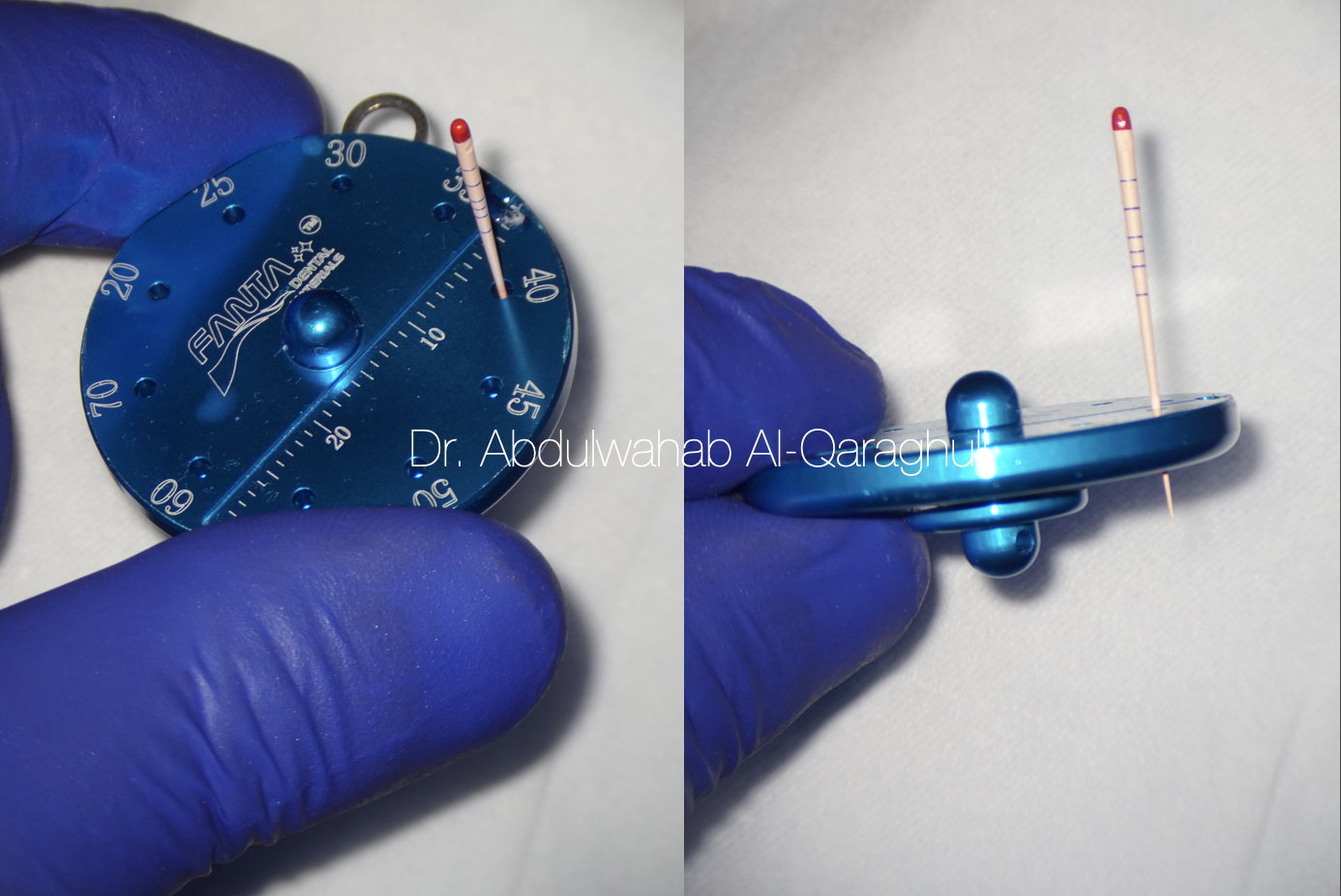

Fig. 27

Apical foramen size for the canals was

#25 for MM

#35 for MB

#40 for ML

#60 for DL

Fig. 28

Adjust the gutta percha point size according to the apical foramen size that we take from apical gauging

Fig. 29

Cone fit it should be checked with wet canal not dry, so it work as lubricant in side the canal as the sealer work

Fig. 30

Starting Irrigation protocol

5.25% NaOCL

17% EDTA

2% CHx

With different time for irrigation

Fig. 31

Warming of sodium hypochlorite in order to increase its activity by obturation pen

Fig. 32

Activation of irrigant solution by ultrasonic

Fig. 33

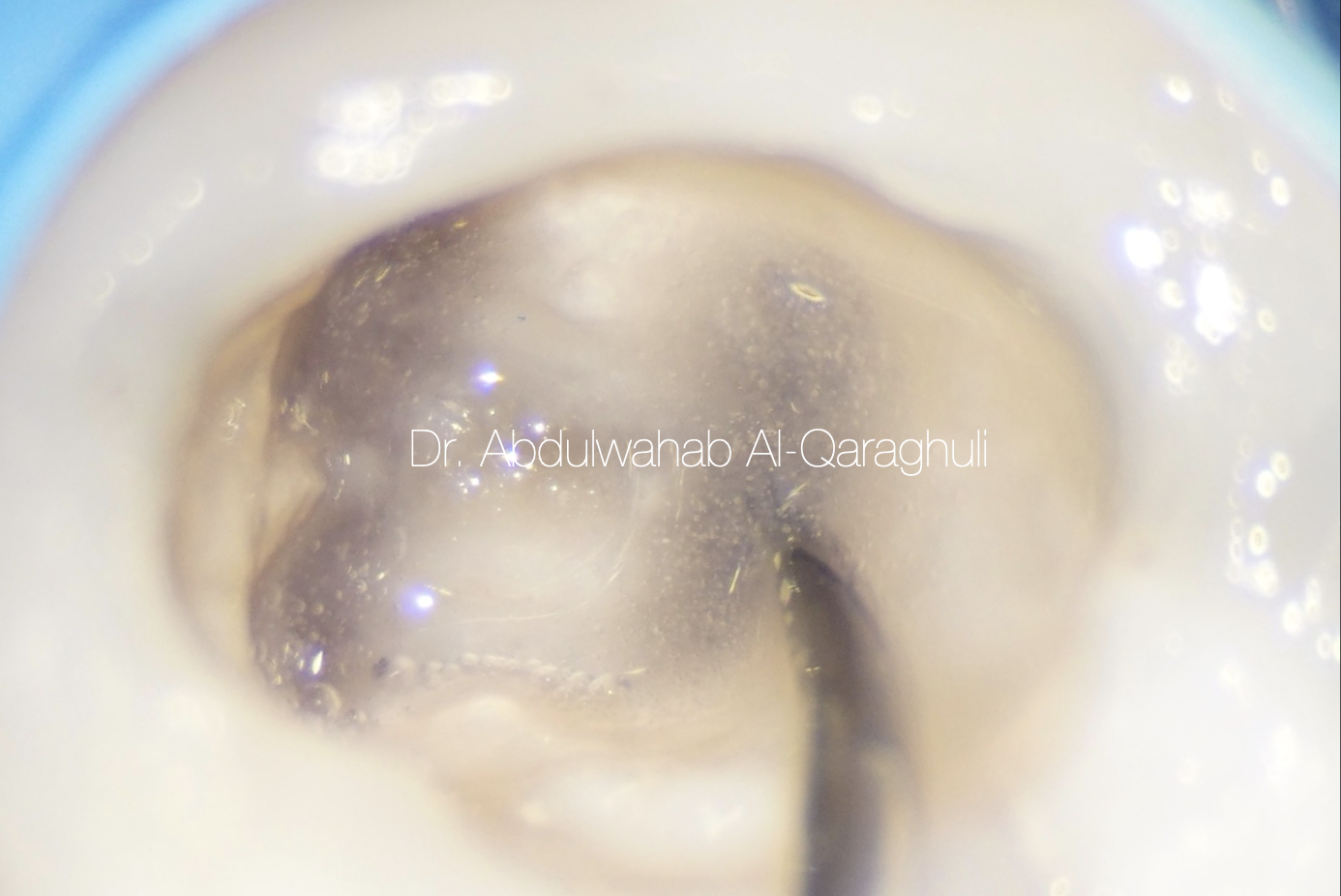

Sodium hypochlorite in action

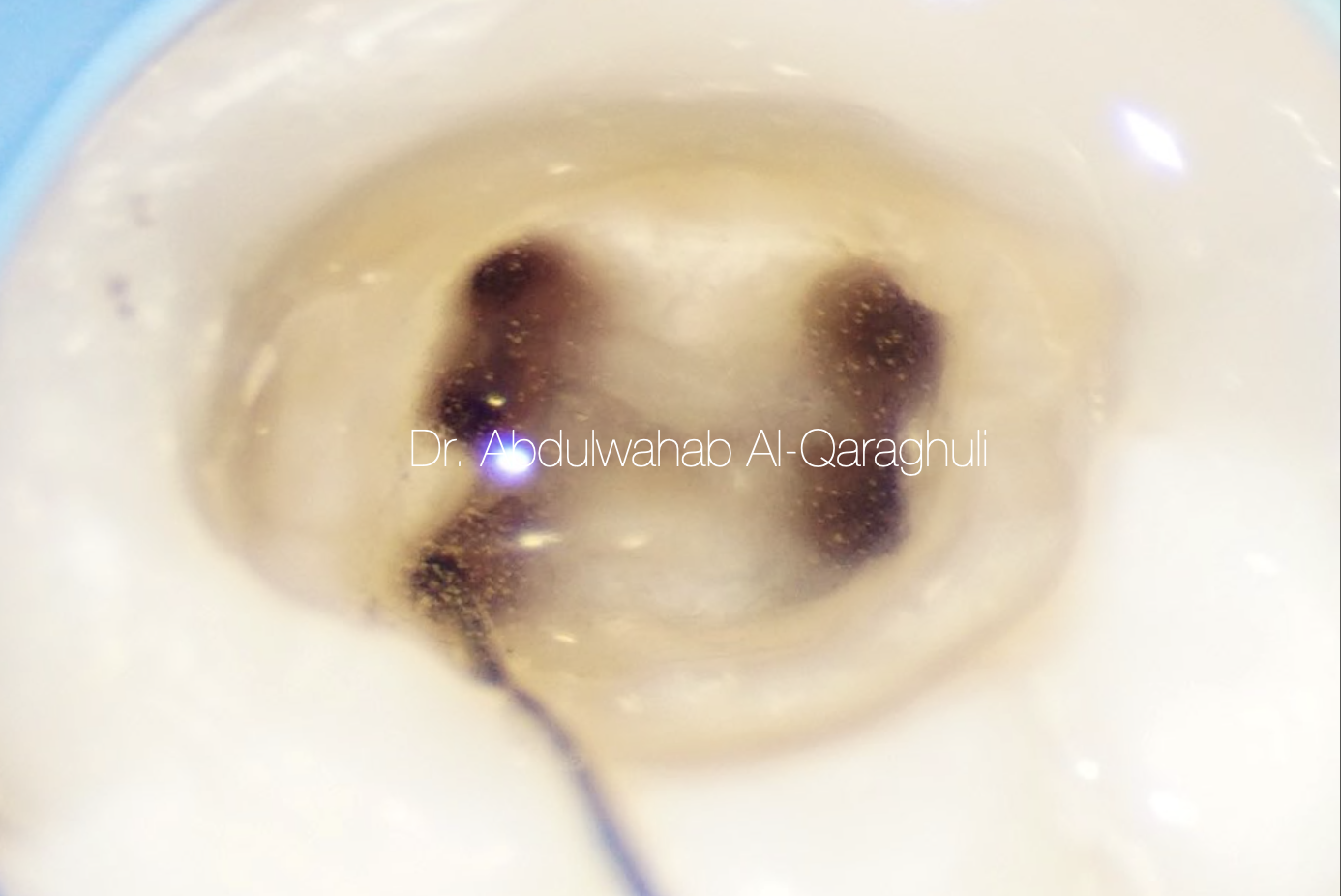

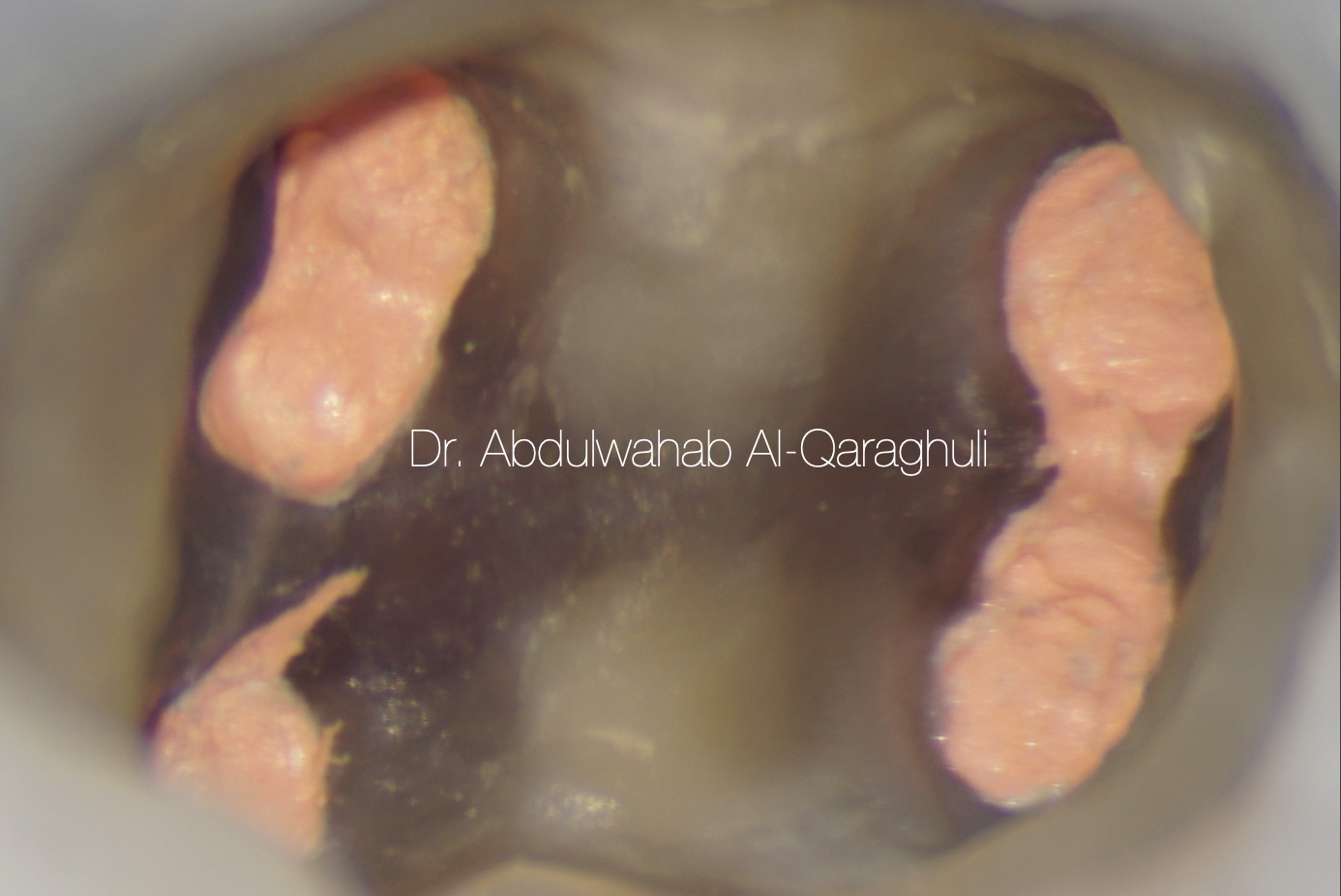

Fig. 34

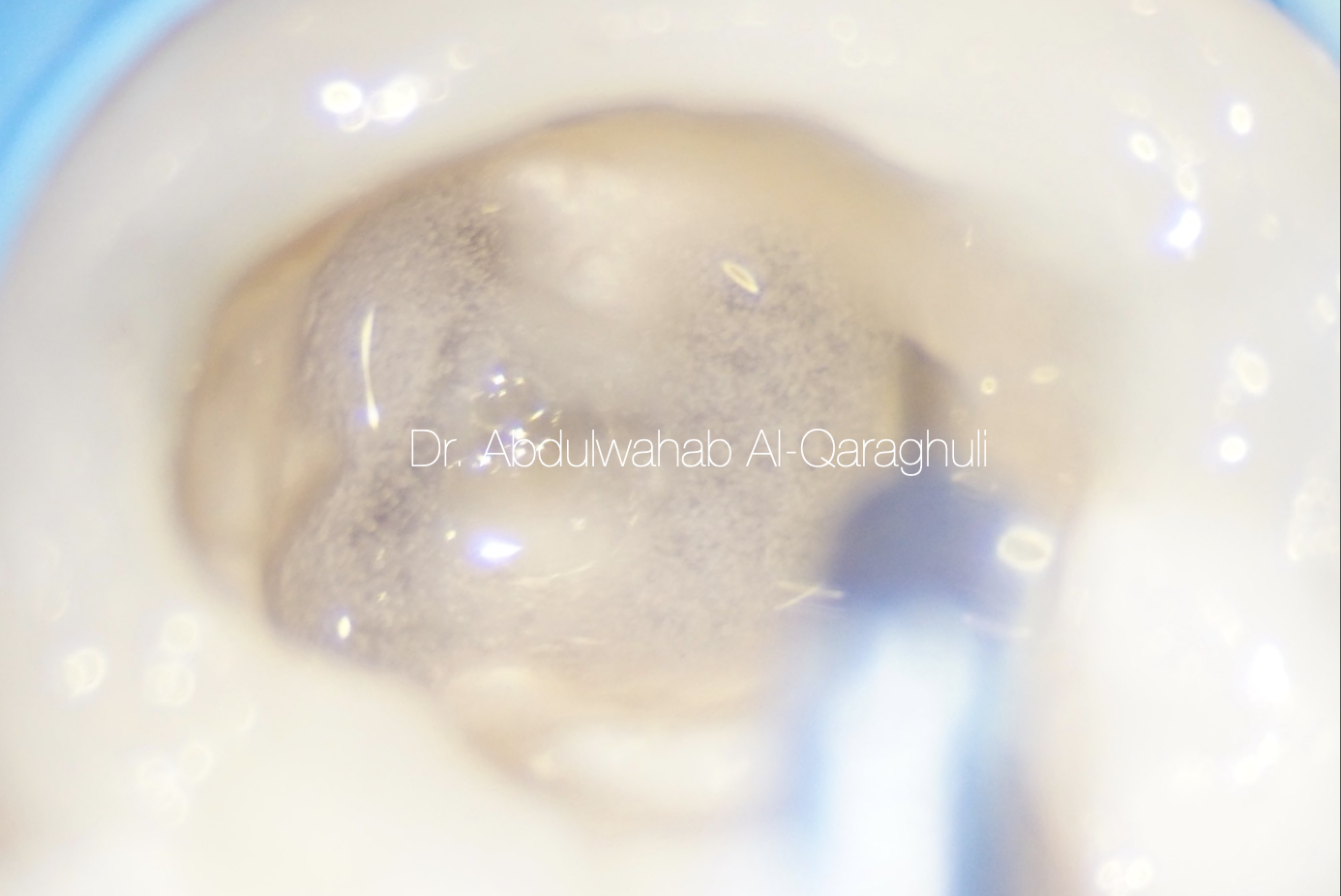

Clean and Ready for obturation

Fig. 35

Obturation by continuous wave of condensation technique (CWC)

Fig. 36

Down pack

Fig. 37

Down pack by x-ray

Fig. 38

Obturation

Fig. 39

Coronal seal with flowable composite

Fig. 40

Final restoration after finishing, polishing and occlusal check

Fig. 41

Post-op X-Ray

Fig. 42

The Author:

Dr. Abdulwahab Al-Qaraghuli

Baghdad - Iraq

2018: B.D.S (Baghdad University)

2021: M.Sc. student (Mustansiriyah University)

2020: Best case of the year at StyleItaliano Endodontics Facebook group

Conclusions

Mandibular molars demonstrate considerable variations with respect to number of roots and root canals. The possibility of additional root canals should be considered even in teeth with a low frequency of abnormal root canal anatomy.

treating additional canals may be challenging, but the inability to find and properly treat the root canals may cause failures. Information on root canal anatomy come from radiographs is valuable and should always be integrated with a careful clinical examination, preferably under magnification for the better and successful endodontic treatment.

Bibliography

1- H. H. Pomeranz, D. L. Eidelman, and M. G. Goldberg, “Treatment considerations of the middle mesial canal of mandibular first and second molars,” Journal of Endodontics, vol. 7, no. 12, pp. 565–568, 1981.

2- F. Wasti, A. C. Shearer, and N. H. F. Wilson, “Root canal systems of the mandibular and maxillary first permanent molar teeth of South Asian Pakistanis,” International Endodontic Journal, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 263–266, 2001.

3- Melton DC, Krell KV, Fuller MW. Anatomical and histolog- ical features of C-shaped canals in mandibular second molars. J Endod 1991, 17:384–8.

4- K. Gulabivala, T. H. Aung, A. Alavi, and Y. L. Ng, “Root and canal morphology of Burmese mandibular molars,” International Endodontic Journal, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 359–370, 2001

5-L. F. Navarro, A. Luzi, A. A. García, and A. H. García, “Third canal in the mesial root of permanent mandibular first molars: review of the literature and presentation of 3 clinical reports and 2 in vitro studies,” Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal, vol. 12, no. 8, pp. E605–E609, 2007.